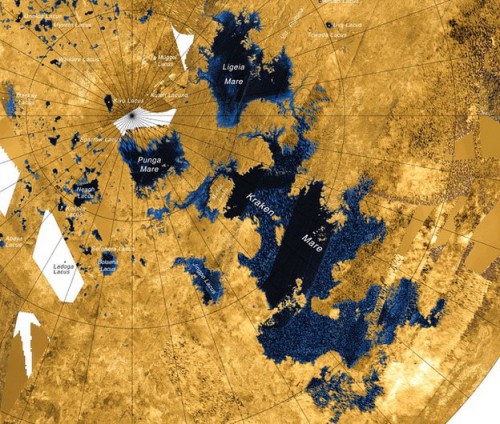

The Cassini spacecraft continues to make new discoveries about Titan’s methane seas and lakes, answering some questions but raising additional ones as well. As announced this week, Cassini has discovered two more of the unusual “magic islands”—bright features which seem to appear in the seas where they didn’t exist before—and has measured the depth of the largest Titanian sea.

The new findings were presented this week at the Division for Planetary Sciences Meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Tucson, Ariz.

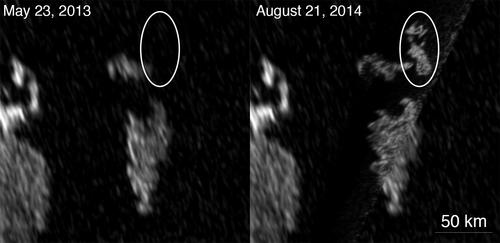

During a flyby of Titan last Aug. 21, Cassini made an intriguing discovery similar to an earlier one: two new mysterious bright features in Kraken Mare, much like the one seen before in another sea, Ligeia Mare. Like the previous bright feature, dubbed “magic island,” the new ones seemed to have appeared where nothing was seen before during previous observations. In this case though, the feature was seen in both radar data and images from Cassini’s Visible and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS). Just what these features are is still unknown, but current theories include waves or floating debris.

As reported in National Geographic, “They could be waves, or they could be something more solid,” according to Jason Soderblom of MIT, a member of the Cassini team. “We definitely know now they are something reflecting from the surface.” As Alexander Hayes of Cornell added, “After ten years there, Titan still can surprise us. Titan has dunes, lakes, seas, even rivers. All this makes Titan an explorer’s utopia.”

Although Cassini won’t be able to re-image the oddity in Kraken Mare during the rest of its mission, it will have a chance to look at the one in Ligeia Mare once more, in January 2015. Any new observations could help scientists to understand what is causing these enigmatic “islands” to appear the way they do.

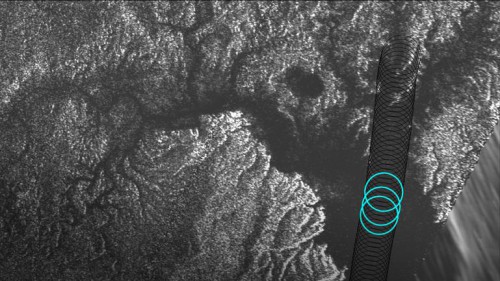

Cassini also used its onboard radar to measure the depths of Kraken Mare, the moon’s largest sea. The radar covered a shore-to-shore track spanning 120 miles (200 kilometers); for 25 miles (40 kilometers) along this track on the eastern shoreline, Cassini measures depths of 66 to 115 feet (20 to 35 meters), shown as the blue circles in the image above. This part of the sea is near a large flooded river valley, which empties into Kraken Mare just as rivers do on Earth.

In other areas of Kraken Mare, the radar did not show an echo from the seafloor, suggesting that the sea is too deep in those areas for the radar beam to penetrate, or possibly that the radar beam was absorbed by the liquid. Other radar data showed steep slopes leading down into the sea along the shoreline, also hinting that Kraken Mare may be quite deep in places. The deeper parts of Kraken Mare have been estimated to be 656 feet (200 meters) deep or more.

In January 2015, Cassini will measure the depth of another sea, Punga Mare, the smallest of three large seas in Titan’s north polar region.

As to determining just what these “magic islands” actually are, that will probably require a follow-up mission. Apart from another orbiter, proposals on the drawing boards include a possible boat, blimp, or airplane to further investigate Titan close-up. Perhaps even a submersible at some point in the future to “plumb Titan’s seas” for real.

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, the European Space Agency, and the Italian Space Agency. NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages the mission for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, Washington, D.C. The Cassini orbiter was designed, developed, and assembled at JPL. The radar instrument was built by JPL and the Italian Space Agency, working with team members from the United States and several European countries.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace