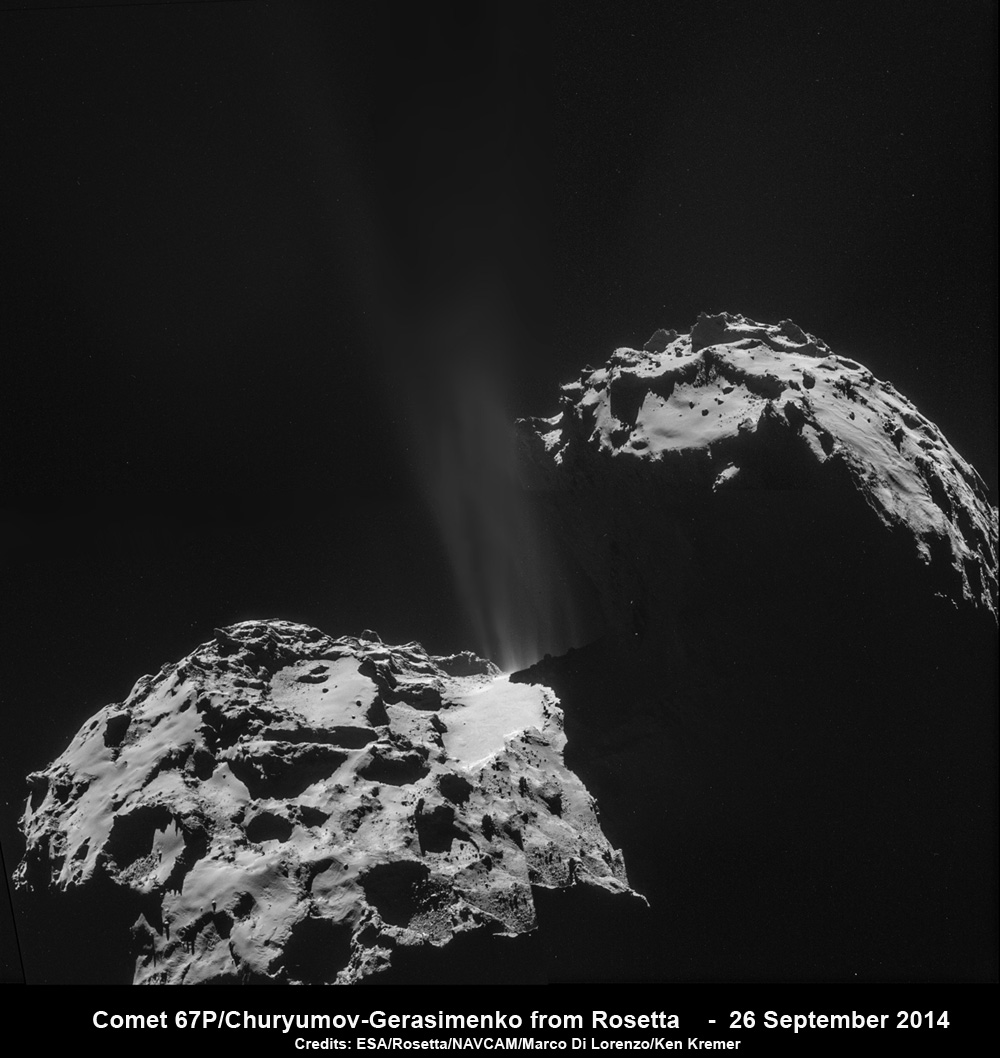

Impacts from cometary debris caused several significant navigation related issues for Europe’s Rosetta orbiter as it flew within 14 kilometers (8.7 miles) of the surface of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko during the probe’s most recent close encounter in late-March.

The high gain antenna drifted, the star trackers were confused, and the spacecraft went into “safe mode,” which temporarily halted science observations, after the probe had a somewhat harrowing encounter with outflows of denser regions of gas and dust particles spewing from the increasingly active nucleus warmed by our Sun as it steadily moves in closer.

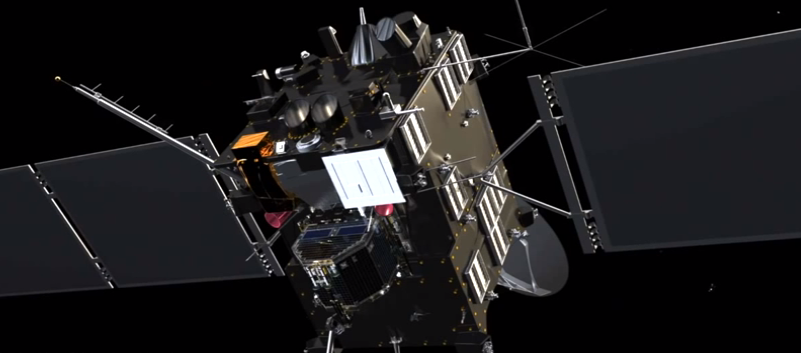

The European Space Agency’s (ESA) Rosetta spacecraft is humankind’s first spacecraft in history to orbit a comet.

And it has performed almost flawlessly since arriving at the bizarre alien world on Aug. 6, 2014, after a decade-long interplanetary journey of some 500 million kilometers (300 million miles) from Earth.

On Saturday, March 30, Rosetta was performing the latest in a series of targeted close flybys aimed at making unprecedented up-close science observations of comet 67P with its suite of 11 state-of-the-art science instruments when it “experienced significant difficulties in navigation,” ESA said in a statement.

“This resulted in its high gain antenna starting to drift away from pointing at the Earth, impacting communications, and was subsequently followed by a ‘safe mode’ event.”

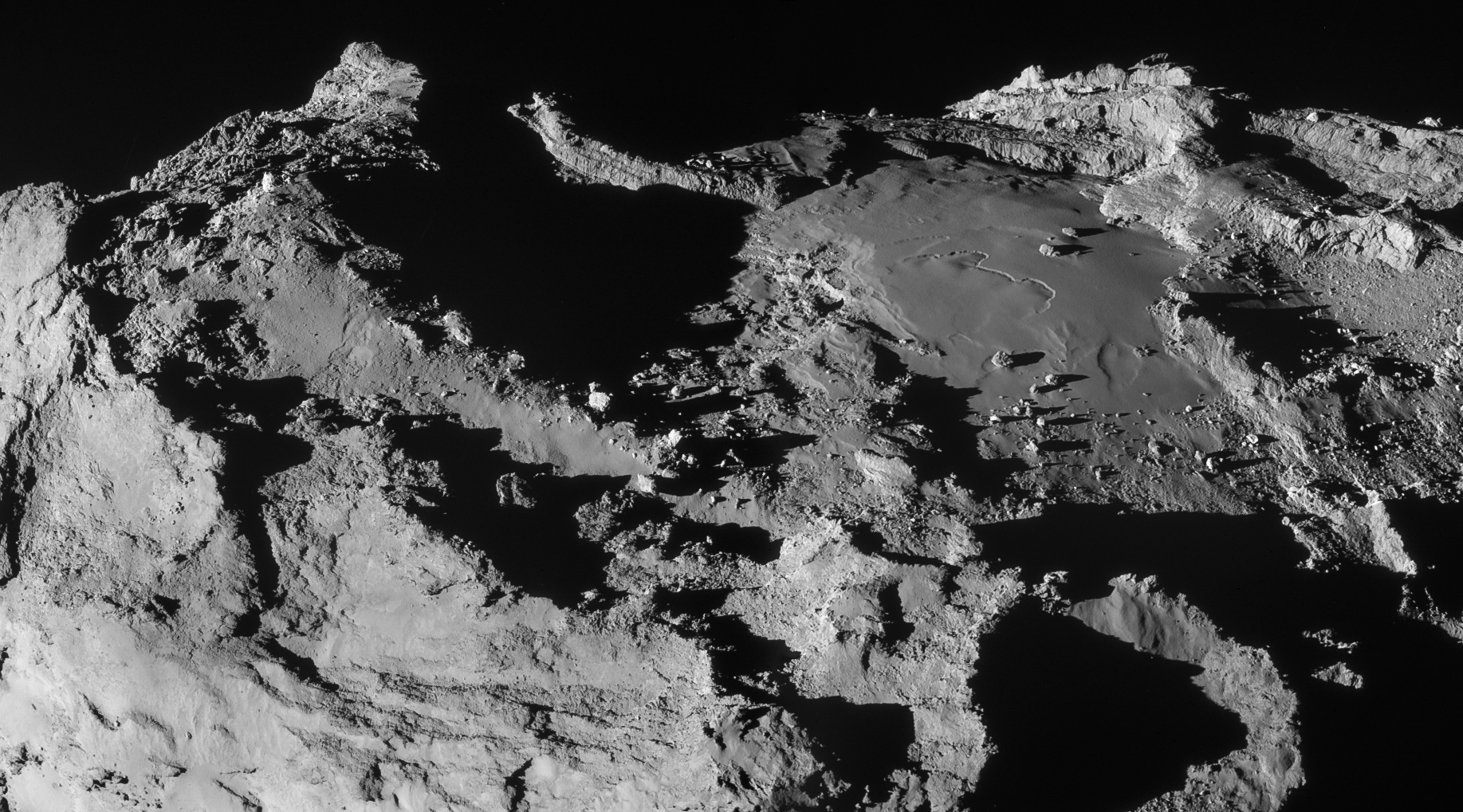

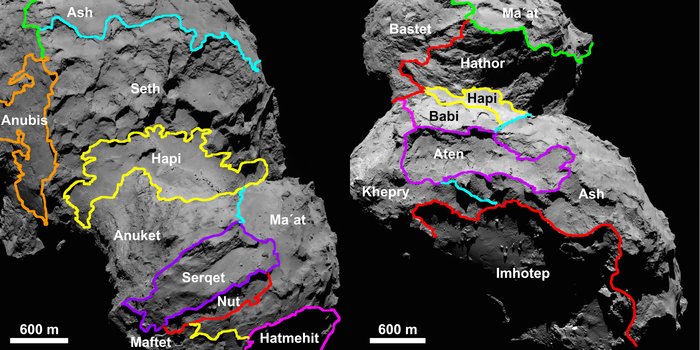

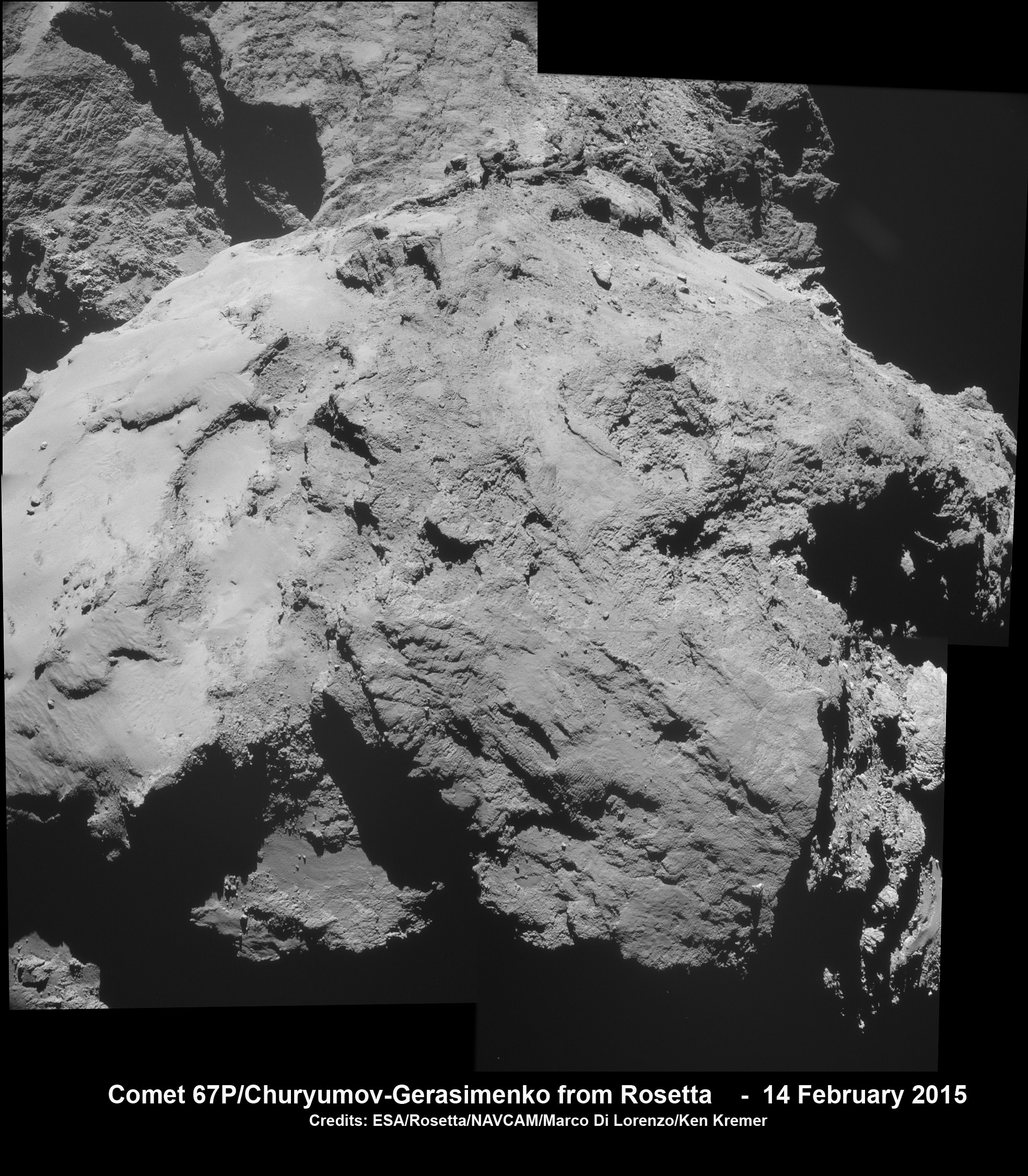

Rosetta swooped to within 14 km (about 16 km, or 10 miles, from the center) of the pockmarked body when it soared over the comet’s large lobe.

The diminutive dual-lobed body shaped like a rubber ducky measures only about 4 kilometers (2.5 miles) wide.

ESA says that communications have been “successfully recovered, but it will take a little longer to resume normal scientific operations.”

Since February 2015, the mission team has planned a series of encounters at a range of distances to gather as much science data as possible.

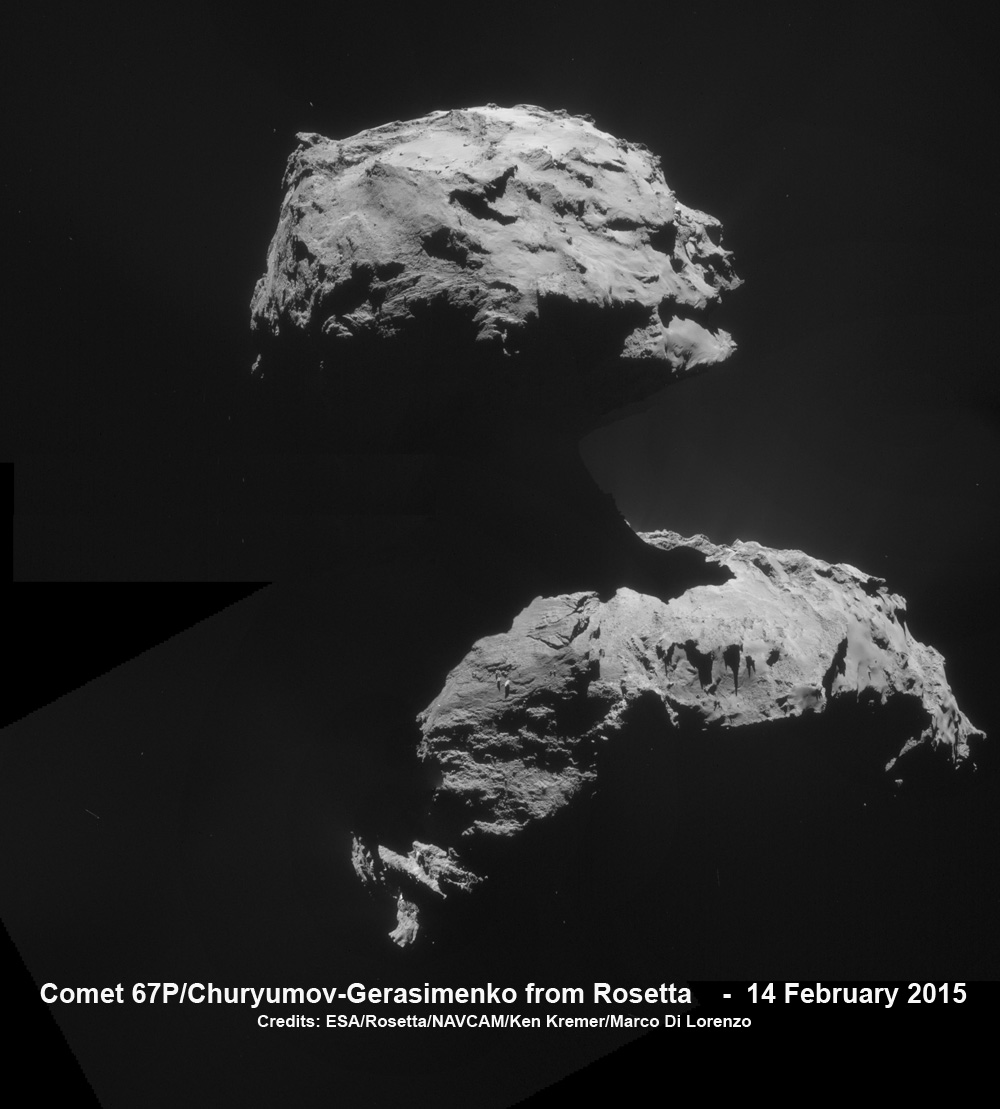

The closest flyby to date took place Feb. 14, coincidentally coinciding with Valentine’s Day, when it took a daring plunge to within 6 kilometers (3.8 miles) over the comet’s Imhotep region, also located on the larger lobe.

When the mission operations engineers target Rosetta to conduct those exciting close encounters for science, they are also purposely exposing the probe to the denser gas and dust regions that are simultaneously scientifically delightful but potentially hazardous because the probe’s large solar arrays experience significantly more “drag.”

During both flybys, the flat solar panels were oriented in a manner perpendicular to the outflowing material, thus maximizing cometary debis strikes and the drag.

In both instances, the hail of debris from comet 67P confused the star trackers by mistaking it for stars.

The star trackers are absolutely crucial in helping control the spacecraft’s attitude and maintain its orientation in space with respect to the Sun and Earth. This is essential for pointing the high gain antenna, used to send and receive signals to and from ground stations on Earth.

So if the star trackers are not functioning properly, Rosetta’s high gain antenna can drift away from pointing to Earth and spacecraft communications could potentially be lost.

“When the star trackers are not tracking, the attitude is propagated on gyro measurements. But the attitude can drift, especially if the spacecraft is slewing a lot,” notes ESA.

In a worst case scenario, the mission would be doomed.

During the March 30 flyby, ESA reported that “the primary star tracker encountered difficulties in locking on to stars on the way in towards closest approach. Attempts were made to regain tracking capabilities, but there was too much background noise due to activity close to the comet nucleus: hundreds of ‘false stars’ were registered and it took almost 24 hours before tracking was properly re-established.”

The high gain antenna also veered away from the Earth and there was “a significant drop in the radio signal received by ground stations on Earth.”

The probe went into an automatic safe mode, as designed, and also shut off the science instruments “to preserve its safety.”

The team immediately went into action and successfully recovered the spacecraft, brought it out of safe mode, and returned it to “normal status,” said ESA.

On April 1, they successfully fired the thrusters to set the probe up for its next flyby Wednesday, maneuvering Rosetta in from a distance of 400 km to 140 km.

Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko is a Jupiter-family comet.

Throughout 2015, Rosetta will observe the comet from varying distances that will also provide context for the data returned.

“Rosetta is providing us with a grandstand seat of the comet throughout the next year,” says Matt Taylor, ESA’s Rosetta project scientist.

Flybys also allow the study of the processes by which cometary dust is accelerated by the cometary gas emission, according to the team.

“We’re in the main science phase of the mission now, so throughout the year we’ll be continuing with high-resolution mapping of the comet,” says Taylor.

“We’ll sample the gas, dust and plasma from a range of distances as the comet’s activity increases and then subsides again later in the year.”

The comet is comprised mostly of water ice and dust, is fluffy, and has a very high porosity of 70 to 80 percent—so it would float on water.

“The nucleus surface itself appears rich in organic materials, with little sign of water ice,” says Taylor.

As of today, April 6, the pair are about 422 million km from Earth and 291 million km from the Sun. That’s over 50 million km closer to the Sun since the Valentine’s Day flyby. They will reach perihelion on Aug. 13, 2015, at a distance of 186 million km from the Sun, between the orbits of Earth and Mars.

And the team is still listening for signs of signals from the Philae lander, which successfully touched down Nov. 12, 2014, and transmitted data.

Stay tuned here for continuing developments.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

One Comment

One Ping

Pingback:Rosetta and Philae Capture First Detailed Magnetic Measurements of a Comet Nucleus « AmericaSpace