Three decades have now passed since one of the most dramatic missions—and one of the most dramatic months—in the shuttle program’s 30-year history. On 29 July 1985, Challenger rocketed into orbit, carrying her eighth human crew on a week-long voyage to explore the Sun and the cosmos with a battery of scientific instruments. As described in yesterday’s AmericaSpace history article, Mission 51F had already endured a harrowing main engine shutdown, seconds before liftoff, on 12 July, but any belief that the seven astronauts had weathered their run of bad luck was sorely mistaken. Six minutes after launch, and 67 miles (108 km) above Earth, a main engine failure necessitated an Abort to Orbit (ATO), marking the only major in-flight abort ever effected during a shuttle launch. Challenger limped into a low, but stable orbit, ready for an ambitious mission, which, despite its scientific bonanza, would forever become known for its role in “The Cola Wars”.

Aboard Challenger that morning was one of the oldest crews ever launched into orbit, with an average age of 47, and just two previous space missions between them. In command was veteran astronaut Gordon Fullerton, joined on the flight deck for ascent by pilot Roy Bridges, flight engineer Story Musgrave—recently interviewed by AmericaSpace’s Emily Carney—and the then-oldest man in space, Karl Henize. Downstairs, on the shuttle’s darkened flight deck, were fellow astronauts Tony England, John-David Bartoe and Loren Acton. And for solar physicist Acton, the sensation of lifting off from Earth was comparable to the Loma Prieta earthquake of October 1989, which hit the Greater San Francisco Bay area and measured 7.1 on the Richter scale.

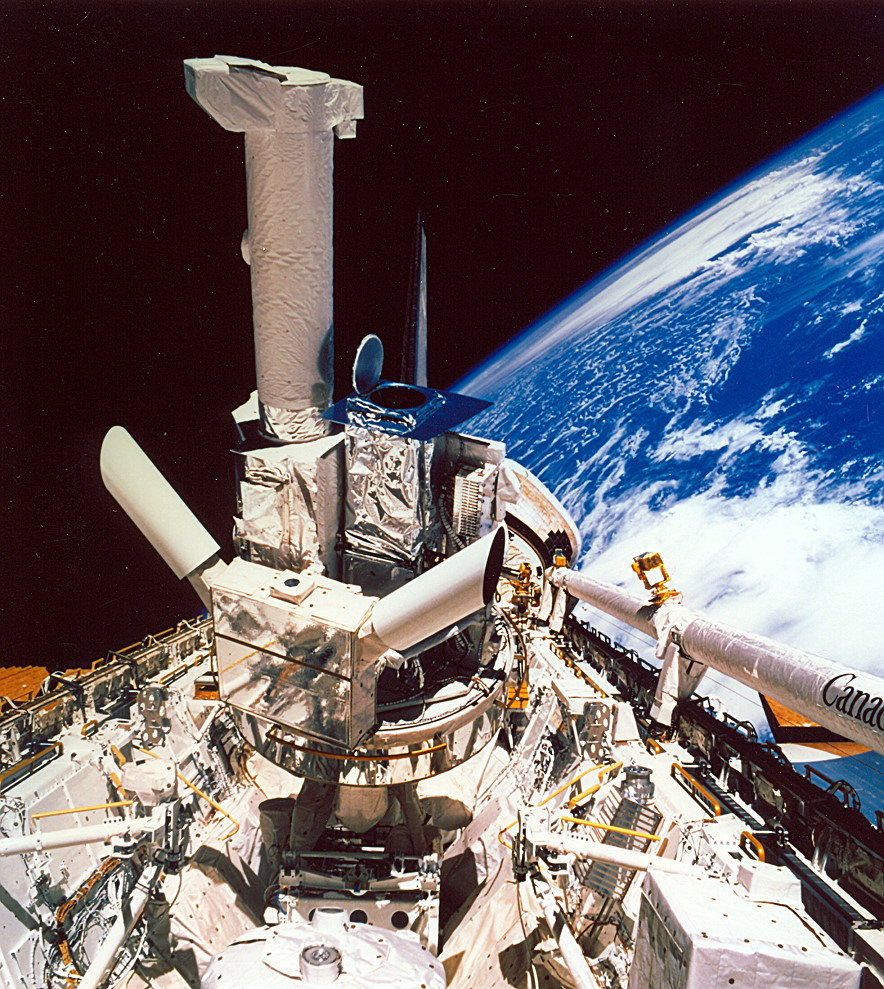

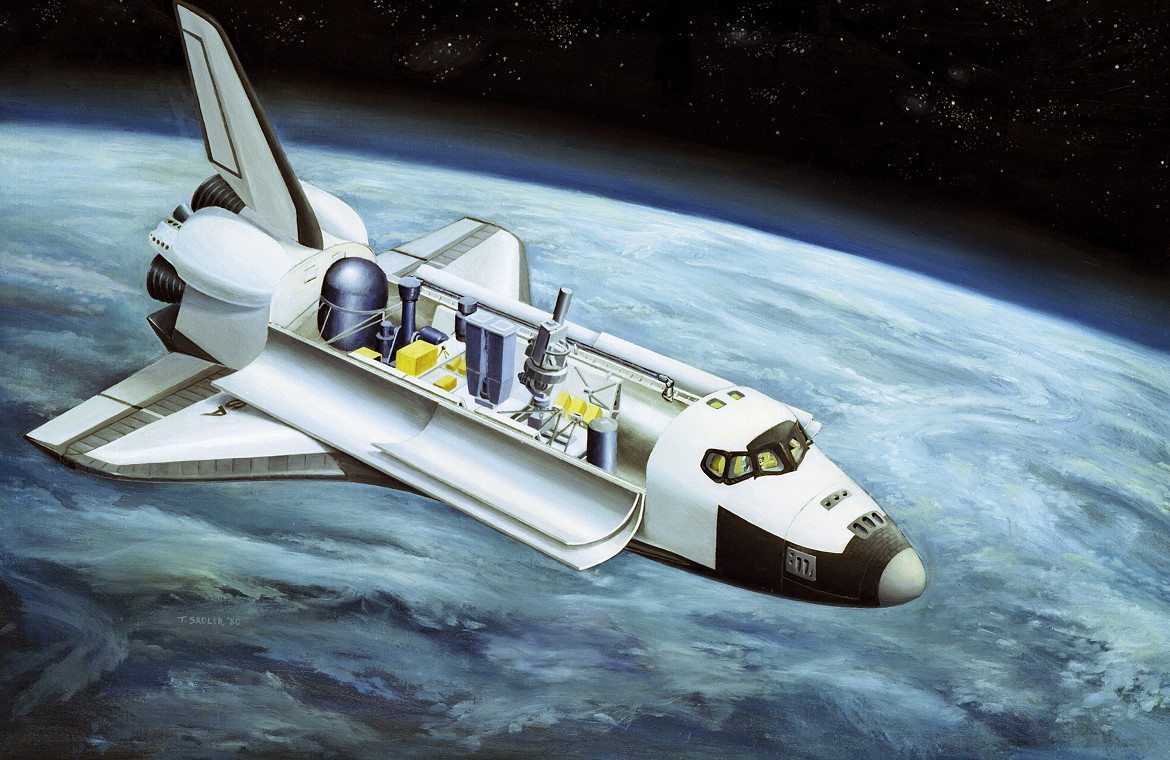

The solar physics instruments aboard Mission 51F—part of the dedicated Spacelab-2 payload—were designed to investigate the Sun’s chromosphere, “transitional” region and corona, in order to better understand the mechanisms responsible for transporting heat from layer to layer. Attached to a large Instrument Pointing System (IPS) in the shuttle’s payload bay were the Solar Optical Universal Polarimeter (SOUP), the Coronal Helium Abundance Spacelab Experiment (CHASE), the High Resolution Telescope and Spectrograph (HRTS) and the Solar Ultraviolet Spectral Irradiance Monitor (SUSIM). Unlike earlier missions, Spacelab-2 consisted of a “pallet-only” configuration, utilizing three unpressurized platforms to hold the instruments. At the rear of Challenger’s payload bay was the Cosmic Ray Nuclei Experiment (CRNE), a giant egg-shaped detector, affixed to its own unique support truss. Mission 51F was arguably one of the most complex research missions ever undertaken with a human crew at that time. In fact, it was noted by the solar physics and astronomical communities that its achievements would likely “stand until the era of the Space Station, because no payload now under consideration matches the complexity of Spacelab-2, which tests the limits of hardware, software and people, everywhere in the system.”

“It was about as multi-disciplinary as you could imagine,” Loren Acton recalled, years later. “One of the things we learned was that we tried to accommodate and carry out a great variety of experiments.” One of those experiments, though, caused some consternation. In the eyes of the world, Mission 51F would become “The Coke and Pepsi Flight”. Even today, Acton admitted, his visits to schools are dominated by questions from children about the intricacies of carbonated drinks in space, rather than the wonders of solar physics. “Coca Cola had gotten permission to do an experiment in space to see if they could dispense carbonated beverages in weightlessness,” Acton recalled. “They got approval to build this special can, put significant money into it and were all set to fly it on one of the early shuttle missions. This was during the “Cola Wars”, when Ronald Reagan was in the White House. Somebody at a high level at Pepsi found out, went to their contacts in the White House and said “This cannot be allowed to happen—that Coca Cola would be the first cola in space”. So the Coke can was taken off the mission it was supposed to go on and Pepsi was given time to develop their own can so that they could both fly on the same flight. It turned out that our mission ended up getting the privilege of carrying the first soda pop in space.”

The astronauts were even instructed to photograph each other drinking the carbonated beverages, with the date/time recording features of their cameras activated, to show which was consumed first. (It turned out to be Coke, but neither drink met with much approval from the crew.) Although subsequent pictures from Mission 51F showed Roy Bridges’ red shift drinking Pepsi and Story Musgrave’s blue team sipping Coke from the dispenser bottles, the distraction for Acton from what was actually an important mission for astrophysical and solar research proved irritating. “The morning before the launch, there is always a briefing, during which all the last-minute things that need to be talked about get talked about,” Acton said later. “We were about halfway through a briefing on the latest data concerning the Sun, when who should walk in, but the chief counsel of NASA, who began to brief us once again on the Coke and Pepsi protocols.”

Acton hit the roof. “We’ve been getting ready for this mission for seven years,” he thundered. “It contains a great deal of science. We have a very short time to talk about the final operational things that we need to know. We don’t have time to talk about this stupid carbonated beverage dispenser test. Please leave!”

The chief counsel turned on his heel and walked out.

Aside from the peculiar media interest in the two colas, the verification of the IPS was a critical mission objective for 51F, particularly in light of its most high-profile future use: the ASTRO-1 mission, planned for launch in March 1986 to undertake ultraviolet observations of Halley’s Comet. “If the IPS doesn’t work,” a senior ASTRO-1 manager explained, “the whole mission is down the drain.” During Challenger’s first day in orbit, tests were performed on the IPS, with the crew unstowing it from its horizontal position on the pallet train and aiming it at several solar targets to verify pointing capabilities and overall accuracy. On 51F, sadly, success took some time to achieve. The SOUP experiment turned out to be somewhat irksome, arousing Acton’s frustration. “About eight hours after its activation,” he said later, “it shut itself off and would not accept the turn-on command. The crew did everything it could, but ended up having to forget it.”

Not until the seventh day of the flight did SOUP awaken. Sadly, Acton had suffered a severe bout of space sickness and the happy news was relayed to him by his blue shift crewmate, John-David Bartoe. “I got sick as a dog,” Acton said years later. “Thirty seconds after the main engines shut off, I felt like my stomach and my innards were all moving up against my lungs. I was sick for four days and learned very quickly that you cannot unfold your barf bag as fast as you barf! When Bartoe came to tell me SOUP was alive, I was feeling so bad I didn’t even get up to go look.”

The success of Spacelab-2 took some time to arrive. The IPS was initially incapable of tracking solar targets smoothly; wandering, as one researcher put it, “like a drunk that can hold it between the ditches, but can’t stay between the white lines”. On the second day of the mission, 30 July, the Houston Chronicle noted that, far from tracking the equivalent of a dime at a range of two miles, the IPS “would do good to hit the broad side of a barn”. At length, the crew and ground-based support teams turned potential defeat into success. SOUP measured vast bubble-like convective cells on the Sun’s surface, whilst CHASE examined the properties of the Sun’s outer atmosphere, revealing that hot, active-region material typically formed “bridges” between the corona and the somewhat cooler chromosphere beneath it. Extensive video and still imagery of the Sun in hydrogen-alpha ultraviolet light were also acquired by HRTS.

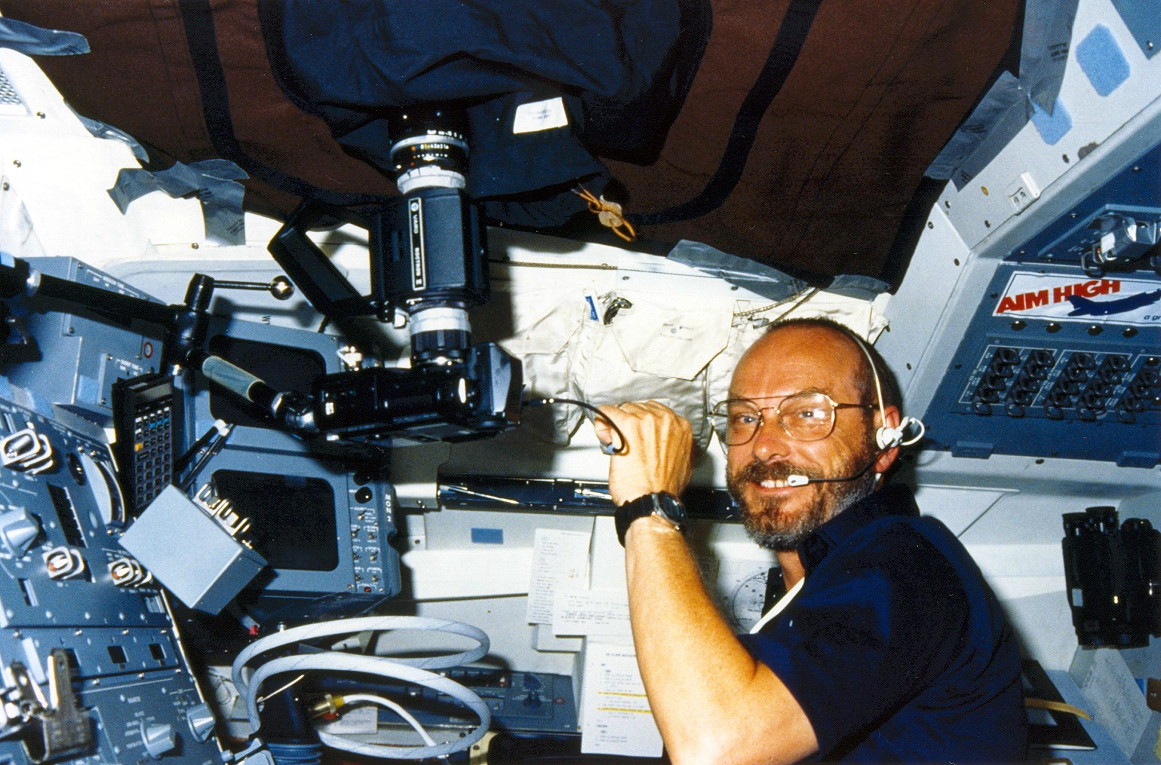

Unlike previous Spacelab missions, this flight did not have the luxury of a pressurized research module and the astronauts worked from the relatively small area at the back of Challenger’s flight deck. “I held a joystick control in my hand, like on a video game,” recalled Bartoe, “that permitted us to move the solar pointing telescopes around to point at particular features on the Sun. We would have a conference call—a solar conference—just before sunrise on each orbit. This gave us a chance to talk to the investigators so we’d know what we were trying to do on that orbit.”

Despite their lack of a Spacelab module, the dual-shift system made Challenger’s flight deck considerably more roomy, with no more than four people on duty at any one time. However, it was also noisy, according to Story Musgrave. “They were banging around all night,” he recalled. “It was hard to sleep. I took a pill to help me to sleep and I forgot I took the pill, so I went off to sleep, just out, floating around. You don’t get the head nods in space. Your head doesn’t fall; there’s no gravity to make that happen, so I went off to sleep and actually I went floating upstairs where my buddies were!” Their astonished reaction as the sleeping Musgrave drifted towards them was to shriek: “Oh! A monster!” Using fingertips, they pushed him back downstairs into the middeck. “I bounced around all night,” Musgrave concluded. There was time for fun, too, with the crew recording a few video shorts of their antics. In one episode, Musgrave and Fullerton—both bald—comically argued at length over a hair brush…

The work schedule, though, was punishing. “During your 12 hours “on”, you ran all these instruments,” recalled Fullerton. “During the 12 hours “off”, you had dinner, slept, had breakfast and then went to work. Two weeks before launch, we set that up. I anchored my schedule to overlap transitions, so if something came up on one shift, I could learn about it and carry it over to the next shift. I also had to stagger things so I got on the right shift for re-entry, so I was in some kind of reasonable shape at the end of the mission. We had the red team sleeping up till launch time, so that once we got on orbit, they were the first one up and they’d go for it for 12 hours. The last week [before launch], we didn’t see the other team or I only saw part of one and part of the other myself.”

Later in the mission, they deployed the Plasma Diagnostics Package (PDP) on the end of Challenger’s Canadian-built Remote Manipulator System (RMS) mechanical arm, to examine the electromagnetic environment surrounding the shuttle. Original plans for Fullerton, Bridges and Musgrave to perform a “flyaround” of the PDP, but limited propellant reserves—caused by the Abort to Orbit (ATO)—eventually made this impossible.

“It was a great mission,” Fullerton later reflected on his second and last spaceflight. “Some of the missions were just going up and punching out a satellite and then they had three days with [very little] to do and came back. We had a payload bay absolutely stuffed with telescopes and instruments.” It proved quite remarkable, journalists reported after the flight ended on 6 August 1985, that Mission 51F had turned into such a grand scientific success after suffering an on-the-pad main engine shutdown, a hairy abort during ascent and the problems with the IPS. “We even made up for the fuel we’d had to dump on the way up because of the engine failure and eked out an extra day on it,” added Fullerton. “We were scheduled for seven and made it eight!”

This is part of a series of history articles, which will appear each weekend, barring any major news stories. Next week’s article will focus on the 25th anniversary of the infamous “Summer of Hydrogen Leaks”, which grounded the shuttle fleet in 1990.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Did the brown staining on the wings and OMS pods (seen in the first image of this installment)burn off during re-entry or did it have to be scrubbed off before the next launch?