Ten years have now passed since the first space shuttle streaked safely back to Earth on 9 August 2005, in the aftermath of the Columbia disaster. The crew of STS-114—Commander Eileen Collins, Pilot Jim “Vegas” Kelly, and Mission Specialists Soichi Noguchi of Japan and NASA astronauts Steve Robinson, Wendy Lawrence, Andy Thomas, and Charlie Camarda—prepared to return home after a spectacular 14-day mission to deliver equipment and supplies to the International Space Station (ISS) and its incumbent Expedition 11 team of Commander Sergei Krikalev and Flight Engineer John Phillips. In the 2.5-year span since the loss of Columbia, significant changes had been implemented across the shuttle program, most visibly manifested in enhanced systems for inspecting the leading edge of the orbiter’s wings, to ensure damage incurred to the critical Thermal Protection System (TPS) could be picked up and addressed before the fiery onset of re-entry. On 8/9 August 2005, the STS-114 became the first shuttle crew to put these new systems to the test.

As described in a previous AmericaSpace article, STS-114 would originally have been the next shuttle flight after STS-107, targeted for launch No Earlier Than (NET) 1 March 2003. Under this plan, Atlantis would have transported a “core” crew of Commander Eileen Collins—who had earlier become the first woman in history to lead a space mission—Pilot Jim “Vegas” Kelly, and Mission Specialists Steve Robinson and Japan’s Soichi Noguchi to the ISS on the first Utilization and Logistics Flight (ULF-1). They would have delivered the incoming Expedition 7 crew of Russian cosmonauts Yuri Malenchenko and Aleksandr Kaleri, together with U.S. astronaut Ed Lu, to the space station to begin a four-month tour of duty, and returned to Earth on 13 March with the outgoing Expedition 6 team of Russian cosmonaut Nikolai Budarin and U.S. astronauts Ken Bowersox and Don Pettit, who were wrapping up their own multi-month residency aboard the international outpost.

Under the original plan, STS-114 was to transport the Italian-built Raffaello Multi-Purpose Logistics Module (MPLM) and attach it to the ISS by means of the shuttle’s Canadian-built Remote Manipulator System (RMS) mechanical arm onto the Earth-facing (or “nadir”) port of the Unity node. Laden with equipment and supplies for the station’s incumbent crew, Atlantis was scheduled to roar into orbit in the early hours of 1 March 2003. At the time of Columbia’s destruction, she was in the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB), having been rolled over from the Orbiter Processing Facility (OPF) on 29 January to be mated to her giant External Tank (ET) and twin Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs), and only days away from rollout to Pad 39B.

The seven astronauts and cosmonauts scheduled to fly uphill on STS-114 had been assigned at separate points throughout 2001. In March, U.S. astronaut Ed Lu, “along with a Russian commander and flight engineer,” were assigned to Expedition 7, who would be delivered to the ISS aboard the shuttle for a four-month tour of duty. A few weeks later, in April, Soichi Noguchi was assigned as a Mission Specialist for what was then designated “STS-113” and expected to fly aboard Endeavour in July 2002, with the expectation that he would likely participate in two EVAs. “Among all tasks in the mission, I take EVA as my main assignment,” he told an audience in January 2003. “I’m assigned as EV1, the primary EVA crew member. I’m responsible for all phases of EVA from training to the specific operation procedures. I feel that I’m the one who is fully in charge of the EVA process from the beginning, including training, to the end, through debriefing, after we’ve landed.”

By August 2001, when Collins, Kelly, Robinson, and the remainder of the Expedition 7 crew—Russian cosmonauts Yuri Malenchenko and Sergei Moschenko—were announced, the flight had been redesignated “STS-114” and scheduled for launch no sooner than November 2002. Delays to the shuttle fleet throughout the summer of the following year pushed STS-114 into the spring of 2003, and the mission eventually settled on a target of 1 March. (However, in the days preceding the loss of Columbia, NASA received Eastern Range approval for a launch attempt on 6 March.) Assuming an on-time liftoff, Atlantis would have docked at the Pressurized Mating Adapter (PMA)-2 interface—then situated at the forward end of the U.S. Destiny laboratory—on Flight Day Three and the STS-114 and Expedition 7 crews would have joined the incumbent Expedition 6 crew. Shortly thereafter, Kelly would have used the RMS to remove the Raffaello MPLM from the shuttle’s payload bay and berthed it onto the Unity node, allowing for the removal of equipment and supplies and three new research racks.

A trio of EVAs by Noguchi and Robinson were planned for the fifth, seventh, and ninth days of the mission, one of whose key tasks was the installation of the second External Stowage Platform (ESP-2)—to be situated on the station’s Quest airlock by means of an ESP Attachment Device (ESPAD)—which would provide eight Flight Releasable Attach Mechanisms (FRAMs) to accommodate Orbital Replacement Units (ORUs). Measuring 8.5 x 14 feet (2.6 x 4.2 meters), ESP-2 would be powered by the Unity node and installed by means of the spacewalkers and Kelly on the RMS. An additional core task was the removal and replacement of one of four 620-pound (280-kg) Control Moment Gyroscopes (CMGs) on the station’s boxy Z-1 truss, which had experienced a failure in June 2002.

Returning to Earth after 12 days, STS-114 would be brought the Expedition 6 crew back home to their families and left the Expedition 7 team aboard the ISS through July 2003. However, the Expedition 7 crew composition had itself changed since their initial assignment. In October 2002, a request was made to the Multilateral Crew Operations Panel (MCOP) to replace “rookie” cosmonaut Sergei Moschenko with his backup, veteran cosmonaut Aleksandr Kaleri, and the change was formally announced by NASA in December. Certainly, training images of the STS-114 and Expedition 7 crews from November 2002 included Kaleri.

At the time of Columbia’s loss, STS-114 was exactly a month away from launch and its crew was immediately stood-down, pending an investigation. In the weeks which followed—as the Columbia Accident Investigation Board (CAIB), chaired by retired U.S. Navy Adm. Harold “Hal” Gehman commenced its complex and laborious task of piecing together the cause of the tragedy—NASA looked ahead to STS-114 as the Return to Flight (RTF) mission. When the CAIB published its final report in August 2003, it identified the primary cause of the accident as a chunk of detached foam from the bipod ramp of the ET during ascent, which had slammed into Columbia’s port-side wing, critically damaging its delicate Reinforced Carbon Carbon (RCC) leading edge. Sixteen days later, when the STS-107 crew returned to Earth, super-heated plasma had entered the wing by means of the RCC breach and destroyed the vehicle. However, in addition to this principal “smoking gun,” the CAIB also uncovered significant cultural and managerial failures within NASA itself and released a raft of 29 recommendations, calling for improved pre-flight inspection routines, better in-flight imagery, and a recertification of all shuttle components by 2010. As NASA dug into the details of the report and prepared for RTF, new systems were implemented, including an Orbiter Boom Sensor System (OBSS) to scan for RCC or other damage at various stages during each subsequent mission.

By the early fall of 2003, STS-114 was targeted to fly no sooner than a four-week “launch window,” extending from 12 September through 10 October 2004, with successive opportunities in January and March 2005. All of these dates were dictated by the CAIB recommendation to launch in the hours of daylight and satisfy thermal constraints at the space station. At the same time, the necessity of the inspections and other tasks prompted NASA to split the STS-114 mission objectives into two discrete flights, for which a pair of shuttle crews were announced in the late fall of 2003. Collins’ original four-member “core” crew was expanded in November with three additional members—Mission Specialists Wendy Lawrence, Andy Thomas, and Charlie Camarda—to handle the significantly increased workload. “STS-114 is going to be a complex developmental test flight and this crew has the right set of skills and experience to get the Space Shuttles flying safely again,” explained NASA Associate Administrator for Space Flight, former astronaut Bill Readdy. “STS-114 was always slated to have a crew of seven, but now, instead of three crew rotating on-and-off the International Space Station, all crew members will be dedicated to the STS-114 mission objectives.” A month later, in December 2003, a four-strong crew of Commander Steve Lindsey, Pilot Mark Kelly, and Mission Specialists Mike Fossum and Carlos Noriega were assigned to STS-121, targeted for late 2004, which would complete the objectives baselined for the original, pre-Columbia STS-114 flight. Subsequent adjustments were made in July 2004 and November 2004, with Piers Sellers replacing Noriega and fellow astronauts Lisa Nowak and Stephanie Wilson joining the STS-121 crew.

As NASA dug into the process of returning the shuttle to operations, the No Earlier Than (NET) target slipped further to the right and by spring 2004 had been moved to March-April 2005 at the soonest. By this stage, the agency’s Space Flight Leadership Council had decided to substitute Atlantis for her sister ship, Discovery, on STS-114, which would be redesignated “Logistics Flight (LF)-1.” It was noted that assessments of the condition of the orbiters’ Rudder Speed Brake (RSB) actuators—one of whose gears had been installed in reverse on both Atlantis and Discovery—together with ongoing analyses of ET foam-loss problems and the construction of the OBSS had been key contributors to the delay and to the switch of orbiter vehicles. By June 2004 efforts to install OBSS wiring and impact sensors in the wing leading edges had gotten underway. Concurrently, efforts to develop ice-reduction heaters and a digital still camera for the External Tank sought to eliminate the need for foam on the troublesome bipod fitting and ensure high-resolution imagery during ascent.

In August, after a lengthy down period for modifications, power was restored to Discovery and normal pre-flight processing operations resumed. However, additional delays triggered by the onslaught of Hurricanes Frances, Ivan, Charley, and Jeanne caused the March-April 2005 launch window to be abandoned, and NASA announced in October that mid-May 2005 was the soonest that STS-114 could potentially fly. “After four hurricanes in a row impacted our centers, it became clear, we needed to step back and evaluate the work in respect to the launch planning date,” Bill Readdy told journalists. “We asked the program to go back and evaluate May and they reported the milestones are lining up. The May launch planning window is based on solid analysis and input from across all elements of the program.” This target date was later refined to a three-week period from 12 May through 3 June.

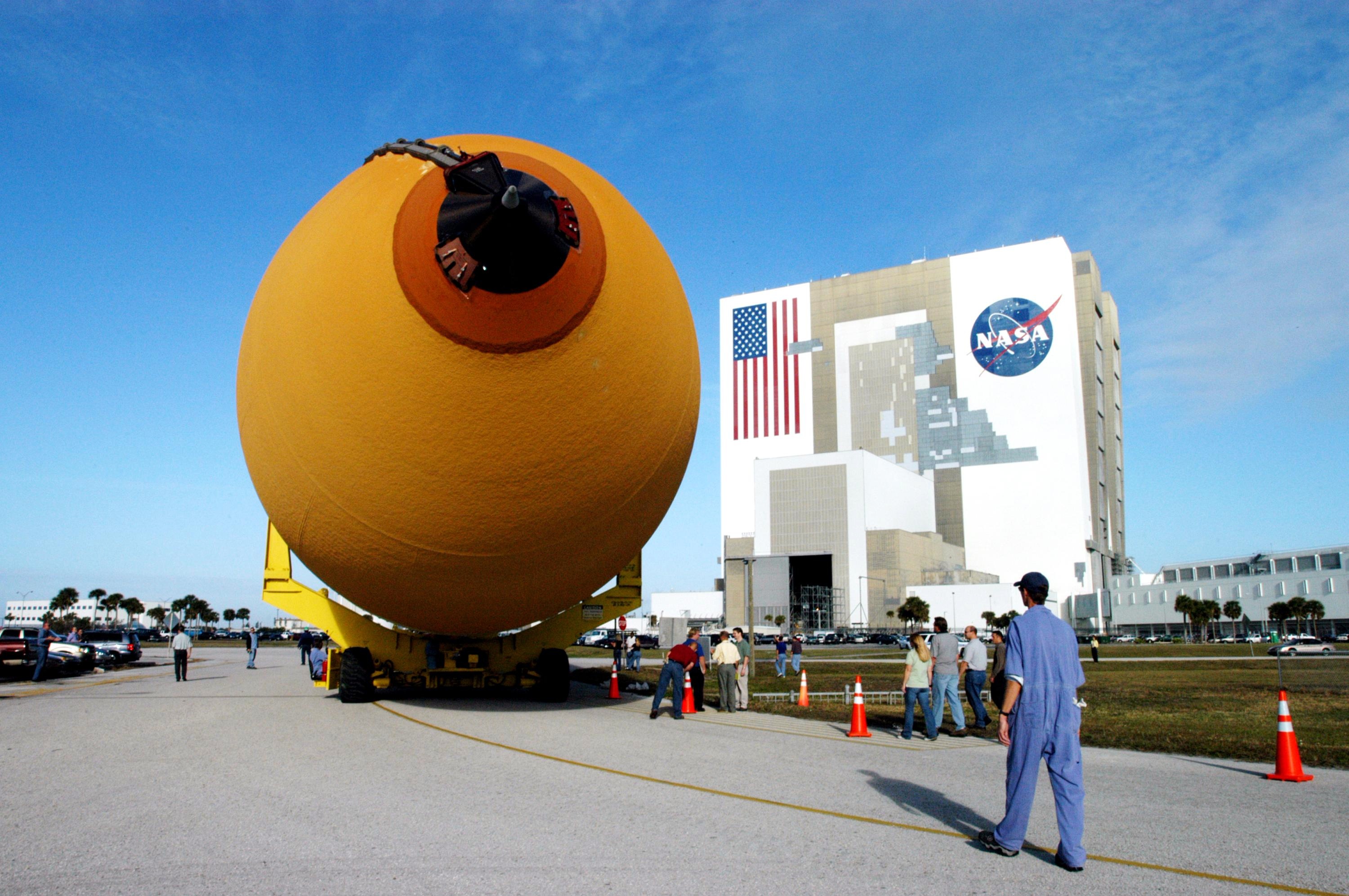

Meanwhile, in October 2004, Discovery’s RMS mechanical arm was installed in her payload bay, and, despite the need to replace its end effector in November, efforts to prepare for rollover to the VAB continued to run relatively smoothly. By mid-December, the shuttle’s cluster of three main engines—No. 2057, 2056, and 2054, with six previous missions between them—were installed, and, according to Discovery’s vehicle manager, Stephanie Stilson, these represented “the last big components to install on the orbiter prior to rolling over.” Finally, on New Year’s Eve, the giant ET departed NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility (MAF) in New Orleans, La., boasting myriad enhancements: an improved bipod fitting, a video still camera to document ascent, reversed bolts on the flange of its mid-section, new spraying procedures for its thermal protection, and a redesigned liquid oxygen feed line bellows. The tank arrived safely at the Cape on 6 January 2005. Almost 23 months since the loss of Columbia, the shuttle system and the ET were ready to return the fleet to orbital operations. “Seeing this tank make its journey to the Kennedy Space Center, where it will be prepared for launch,” said NASA Deputy Associate Administrator for the ISS and Space Shuttle Programs, Michael Kostelnik, “makes it clear how far we’ve come in making the shuttle a safer spacecraft for our astronauts.”

By mid-January, stacking of the twin SRBs for STS-114 had been completed in the VAB, and the ET was mounted onto the stack on 2 March. By this stage, the opening of the STS-114 launch window had been slightly realigned to 15 May, in order “to accommodate daylight launch and to ensure detailed, clear photography of the External Tank.” Final adjustments to payload bay wiring pushed back the rollover of Discovery from the Orbiter Processing Facility (OPF) to the VAB by a few days to 29 March. It had been almost four years since her last voyage into orbit on STS-105 in August 2001; at the time of Columbia’s loss, she was in the midst of a lengthy Orbiter Major Modification (OMM) period, involving 107 enhancements, and had received a further 41 improvements since STS-107. After the shuttle had been attached to the ET/SRB stack—and notwithstanding the discovery of a tiny, hairline crack in the fuel tank’s insulation—the complete STS-114 vehicle was transported to Pad 39B on 7 April.

In the days which followed, the fully fueled ET and Main Propulsion System (MPS) underwent an 11-hour “tanking test,” which helped to demonstrate the new bipod heater mechanism. At around this point, the launch date was moved to NET 22 May, in order to provide “additional time to complete the required engineering analysis, validation and verification testing of the shuttle for a safe Return to Flight.” Within days, however, a more substantial slip came into effect. On 29 April, NASA announced that Discovery would not fly in the May-June window, but that the STS-114 launch would instead occur within a 19-day period from 13-31 July. Citing the need for further validation of engineering analyses and additional ET enhancements, it was noted by newly appointed NASA Administrator Mike Griffin that “we’re going to return to flight; we’re not going to rush to flight.”

A significant driver in the delay was the necessity for a second ET tanking test, which took place on 22 May. During the course of the April test, intermittent readings were noted from the tank’s liquid hydrogen sensors—one of whose responsibilities were to act as a low-level fuel gauge for the shuttle’s three main engines—and a troublesome pressurization relief valve was also causing problems. It was deemed prudent to roll the STS-114 vehicle back to the VAB for destacking and replace the ET/SRBs with the set originally earmarked for STS-121, previously scheduled to fly in the July window. This second tank, which included an ice-prevention heater on the feedline bellows, had arrived at KSC from MAF in mid-March, and its pre-flight processing flow was correspondingly well underway. Following the second tanking test on 20 May, the STS-114 stack was transported back to the VAB on the 26th and Discovery was removed and lowered into the transfer aisle.

As efforts to stack her onto the new ET/SRB set got underway, the opportunity was also taken to perform borescope inspections after the recent detection of hairline cracking in one of the shuttle’s landing gear doors. By 7 June, Discovery had been mated to the new tank and boosters, and, despite a slower than intended rollout, caused by the need to regularly check overheating bearings, the STS-114 stack was back on Pad 39B shortly after noon EDT on the 15th. The stage was now set for the installation of her primary payload—including the Raffaello MPLM, the Lightweight Multi-Purpose Experiment Support Structure Carrier (LMC), containing a replacement Control Moment Gyroscope (CMG), and the ESP-2 spares pallet—which arrived at the pad on 13 June and was installed a few days later. For STS-114, Raffaello was carrying 12 large research racks, including the Human Research Facility (HRF)-2, to be located aboard the station’s Destiny laboratory.

Late in June, the two-day Flight Readiness Review (FRR) confirmed the team’s readiness to support and opening launch attempt at 3:51 p.m. EDT on 13 July, kicking off a 12-day mission to the ISS. Countdown operations commenced on the 10th, and the seven astronauts arrived at Pad 39B by 12:30 p.m. on the 13th. However, less than an hour later, the launch attempt was scrubbed, due to the failed test of one of four low-level liquid hydrogen cut-off sensors aboard the ET. The crew was extracted from Discovery, in anticipation of a second launch attempt on the 14th. However, as troubleshooting got underway, this quickly proved untenable and T-0 was rescheduled for no sooner than the 17th. Following the draining of the ET’s propellants, the troublesome sensor registered itself as “wet,” when it should have been “dry.” Liftoff was pushed back until later in the month, which would bring STS-114 near to the 31 July closure of the window, although Space Shuttle Program managers remained confident that they could get Discovery into orbit before the end of the month.

“My crew will remain in quarantine for the near future, maintaining our proficiency for this mission,” Eileen Collins reported in the aftermath of the delay. “We are keeping in close touch with the troubleshooting plan; we have confidence that the best people are working it. In fact, the plan our engineers have put together is impressive and we are very proud of the work they are doing. While the launch delay is disappointing, we have strong confidence that the mission will launch safely and successfully and we fully support our NASA leadership for taking the time required to understand the problem.”

At length, it was announced on the 19th that a revised launch attempt would be made on the 26th, with the window opening at 10:39 a.m. EDT. Early that morning, the seven astronauts were awakened, showered, breakfasted, and were assisted into their bright orange Launch and Entry Suits (LES) in the Operations & Checkout (O&C) Building. They subsequently departed the O&C Building—to the cheers of spectators and well-wishers—and boarded the Astrovan for the journey to Pad 39B, where they were ensconced in their seats aboard Discovery. By 10:30 a.m., the countdown emerged from its final pre-planned hold at T-9 minutes. It was time to get serious.

The second part of this article will appear tomorrow.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

2 Comments

2 Pings & Trackbacks

Pingback:‘A Wonderful Moment For Us All': 10 Years Since Discovery Came Safely Home to Earth (Part 2) « AmericaSpace

Pingback:Firing Up the Shuttle: Looking Back at the Flight Readiness Firings (Part 2) « AmericaSpace