Thirty years ago, this week, in October 1985, Atlantis became the fourth member of NASA’s Space Shuttle fleet to launch into space, when she flew the classified Mission 51J. It was the start of an illustrious career, which would see her visit space 33 times, visit the International Space Station (ISS) 12 times, visit Russia’s Mir orbital complex a record-setting seven times, visit the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) once and—more than any of her sister orbiters—stage as many as five missions for the Department of Defense. As outlined in yesterday’s AmericaSpace article, she got off to a spectacular start, by setting an empirical landing-to-launch record for a single shuttle of just 50 days, between her first and second missions, but her ambitions for 1986 were cut short by the Challenger tragedy. Following the resumption of shuttle operations in the fall of 1988, Atlantis performed numerous missions which lofted a multitude of payloads into orbit. By the summer of 1992, she had flown 12 times and was ready for her first Orbiter Maintenance Down Period (OMDP). And this was the first instance of Atlantis being in the right place at precisely the right time.

Under original plans—outlined in NASA’s “Payload Flight Assignments NASA Mixed Fleet” document, released in January 1992—the vehicle’s first major period of inspection and maintenance was expected to be comparatively routine. Atlantis would be withdrawn from operational service in the aftermath of her STS-46 mission in August 1992 and would spend several months at prime contractor Rockwell International’s facility in Palmdale, Calif., before returning to the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida to fly STS-57 in June 1993. However, only weeks before STS-46, the first negotiations were underway between the respective governments of the United States and post-Soviet Russia for an expansive joint series of piloted space missions. Already, in the summer of 1991, they had agreed to fly a cosmonaut on the shuttle and an astronaut for several months aboard Mir. However, this plan broadened in mid-1992 to include at least one shuttle-Mir docking mission and several long-duration expeditions by NASA astronauts. By 1 July 1992, a few weeks before she launched on STS-46, it was official: Atlantis’ OMDP would be the first orbiter to receive “modifications to conduct a joint docking mission with the Russian Mir space station.” It was also noted that she would receive the Extended Duration Orbiter (EDO) capability, allowing her to remain in orbit for up to 28 days. “We estimate it will require about a year to modify 104,” explained then-Space Shuttle Program Manager Tom Utsman, referring to Atlantis by her Orbiter Vehicle (OV) designator. “Performing the work at Palmdale gives us the added advantage of being able to maintain a skilled, highly effective workforce in California, which is essential for us to carry out our structural spares work.”

By this time, Atlantis’ OMDP had expanded considerably in scope. After STS-46—the final shuttle mission to fly without a landing drag chute—she was flown atop the Boeing 747 Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA) from Florida to California on 28 October 1992 and spent a total of 19 months on the West Coast. She was outfitted with improved nose-wheel steering, uncommanded brake pressure enhancements, a drag chute in her aft compartment, elevon cove repair and thermal system modifications, new Auxiliary Power Unit (APU) connections, a fifth Power Reactant Storage and Distribution (PRSD) tank set, and the plumbing and electrical connections necessary for future EDO missions. “We’ve added substantially to the cryogenic capability of the vehicle,” said Atlantis’ flow director, Conrad Nagel, “which will allow us to remain in orbit longer than before.” Preparatory work was also undertaken to equip her with the Orbiter Docking System (ODS), to render her compatible with Mir, although the full installation of this hardware was not expected to occur until Atlantis had returned to KSC. Finally, in late May 1994, she was officially turned over by Rockwell to KSC’s Lockheed Space Operations team and returned to the Cape, in order to be readied for STS-66, her first flight in more than two years.

Atlantis’ 13th mission, which got underway on 3 November 1994, was also her longest to date, returning to Earth after almost 11 days in space. Coming only weeks after the successes of STS-64 and STS-68, flown by her sisters Discovery and Endeavour, she also set a three-flight, launch-to-launch record in the post-Challenger era of just 55 days, which would never be surpassed throughout the remainder of the 30-year shuttle program. Only the pre-Challenger era—which saw Mission 51J, 61A and 61B fly all launch in a 54-day span from 3 October to 26 November 1985—achieved better. STS-66 carried the third and final Atmospheric Laboratory for Applications and Science (ATLAS-3) payload and deployed and retrieved the Shuttle Pallet Satellite (SPAS), which was equipped with a battery of infrared Earth-observation sensors. During rendezvous with SPAS, Atlantis’ crew approached the satellite from “beneath,” along the “R-Bar” (or “Earth Radius Vector”), which differed from the “V-Bar” (“Velocity Vector”) profile adopted on previous missions. This technique, which allowed the shuttle to exploit Earth’s natural gravitational gradient to brake her approach and minimize disruptive thruster firings, was being trialed in advance of the Mir docking missions and would also be utilized throughout the ISS era.

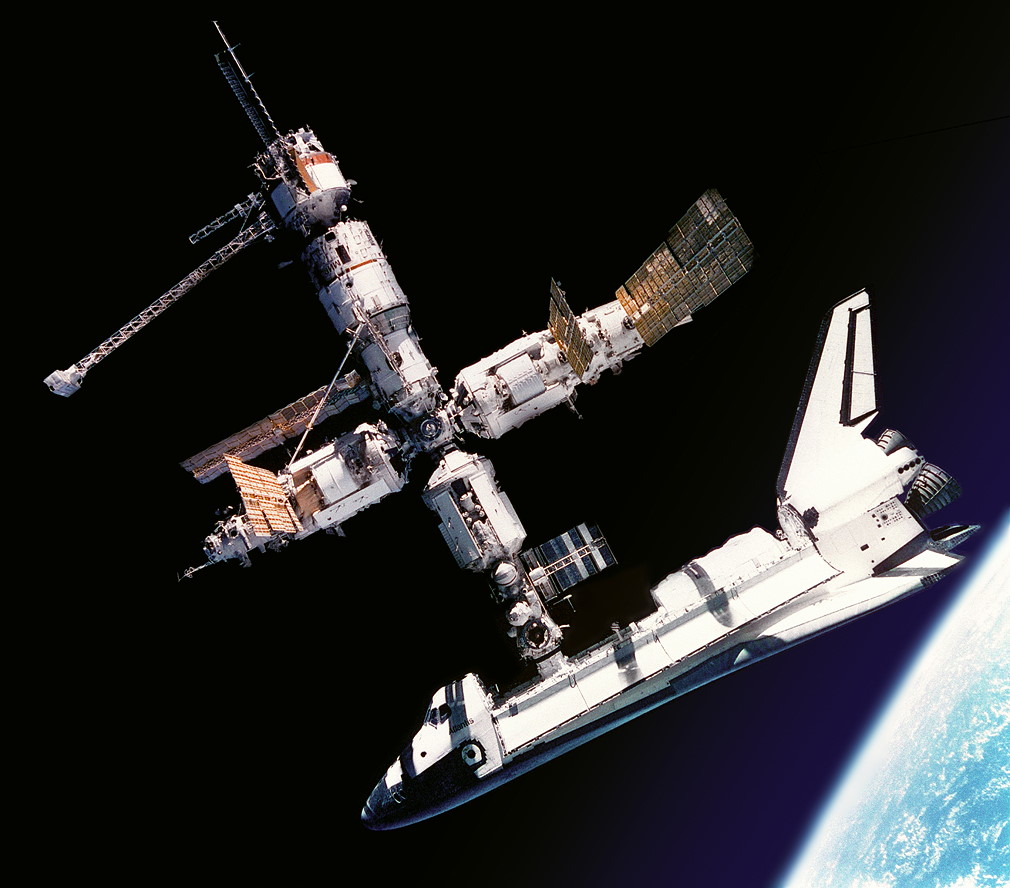

The following year, 1995, saw Atlantis visit Mir not once, but twice, becoming the first shuttle in history to dock with another, inhabited object in space, when she linked up with the Russian space station in the summer of 1995. STS-71, launched on 27 June, arrived at Mir two days later, bringing five U.S. astronauts and a new station crew of Russians Anatoli Solovyov and Nikolai Budarin, which she exchanged for the outgoing station crew of cosmonauts Vladimir Dezhurov and Gennadi Strekalov and NASA’s Norm Thagard for the journey back to Earth. By launching with seven members and landing with eight, STS-71 marked the first time in the shuttle era that an orbiter had returned from space with a larger, and different, crew. It was also the first (and only) time that Atlantis spent U.S. Independence Day in space, an occasion marked with some resonance when the shuttle undocked from Mir to begin her voyage home. Commander Robert “Hoot” Gibson—the first and only person to command two flights of Atlantis—described the event as nothing less than a “cosmic ballet.”

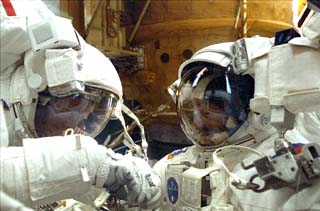

Over the course of the next two years, Atlantis flew six more times to Mir, delivering long-duration U.S. residents Shannon Lucid, John Blaha, Jerry Linenger, Mike Foale, Dave Wolf, and Andy Thomas for multi-month residencies aboard the station. She supported two EVAs—on STS-76 in March 1996 and STS-86 in October 1997—which established their own empirical records. In the former case, it was the first time a shuttle-based spacewalk had ever been performed outside a space station, whilst in the latter case Russian cosmonaut Vladimir Titov became the first non-American to participate in an EVA, clad in a U.S. space suit, and also tested the first “production” version of the Simplified Aid for EVA Rescue (SAFER). On STS-74 in November 1995, she also delivered a docking module to Mir, in order to support future shuttle dockings at the station’s Kristall module. “Atlantis has a history of being the shuttle that did the most international things,” Emily Nelson, lead flight director for the vehicle’s “First-Last” mission on STS-132, later remarked. “It’s the orbiter that the Russians have known best, because it’s one that came to their space station most often and it’s one that we used to deliver a module for them in the past.” In flying a total of seven shuttle-Mir missions between June 1995 and October 1997, Atlantis visited the Russian outpost more times than any of her sister orbiters and, carrying the Spacehab pressurized logistics module in her cavernous payload bay, transported as much as 7,315 pounds (3,318 kg) of water and supplies uphill on each mission.

By the time Atlantis returned to Earth at the end of STS-86, her second-longest mission to date, on 6 October 1997, she had completed 20 flights over a 12-year span and had totaled more than 150 cumulative days in space. During those flights, she had also provided an orbital home for several men and women who would rise significantly through the ranks within NASA, including today’s Administrator, Charlie Bolden, as well as former Deputy Administrator Fred Gregory and the incumbent Director of the Johnson Space Center (JSC), Ellen Ochoa. Less than 24 hours before touching down at the end of STS-86, Atlantis passed another significant milestone, as the five-orbiter shuttle fleet passed two years of combined time spent in space, since the maiden voyage of Columbia, way back in April 1981. By the time of the final shuttle flight in July 2011, the fleet would have accrued more than 1,300 days—or 3.5 years—in orbit, of which Atlantis secured herself in second place for the most-flown orbiter, with more than 306 days across the 33 missions of her career.

In the aftermath of STS-86, Atlantis entered her second OMDP, which would prepare her for an expansive role in the construction and maintenance of the ISS. Five weeks after she returned to Earth, on 11 November 1997, she was flown, via the Boeing 747 SCA, to Palmdale, Calif., for several months of modifications. During her time on the West Coast, Atlantis received the “definitive” ODS system—including the removal of her internal airlock and its replacement in the forward quarter of the payload bay—and numerous weight-saving enhancements, such as the replacement of Advanced Flexible Reusable Surface Insulation (AFRSI) thermal blanketing on her mid- and aft-fuselage, payload bay doors and vertical stabilizer with Nomex Felt Reusable Surface Insulation (FRSI). Additionally, her three Tactical Air Navigation (TACAN) units were removed and the wiring and controls were fitted for an improved, three-string Global Positioning System (GPS) system, whose receivers were to be installed after her return to KSC. Significantly, Atlantis also became the first orbiter to be equipped with the Multifunction Electronic Display Subsystem (MEDS), an upgraded “glass cockpit,” which resulted from a lengthy engineering effort to replace her outdated suite of flight deck instrumentation. The new cockpit consisted of 11 color multifunction display units and made its first flight on STS-101 in May 2000.

Returning to Florida on 27 September 1998, atop the Boeing 747 SCA, Atlantis was transferred the next day from the Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF) into the Orbiter Processing Facility (OPF), to be readied for STS-101. At the time, her next mission—and her first voyage to the nascent ISS—was targeted for August 1999, but lengthy delays ensued, as the Russian-built Zvezda service module met with significant delay and pushed the entire shuttle assembly manifest into disarray. Originally, STS-101 was intended to fly after the launch of Zvezda, in order to outfit the new module, prior to the arrival of the station’s first long-duration crew on Expedition 1. However, as Zvezda’s launch slipped into the summer of 2000, it was recognized that STS-101 would need to fly ahead of it to perform critical maintenance work on the rest of the station, some of whose components were approaching the limits of their operational lifetime, having been in orbit since November 1998. Targeting a launch of STS-101 in April 2000, she was finally rolled into the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) in mid-March for stacking onto her External Tank (ET) and twin Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs). As will be described in tomorrow’s concluding segment of this five-part series, STS-101 marked the first of 12 dedicated missions by Atlantis to the ISS, which would see her deliver more elements of the Integrated Truss Structure (ITS) than any of her sisters, together with two key laboratory modules for the United States and Europe and the long-awaited Quest airlock.

The final part of this five-part article will appear tomorrow.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace