For almost five decades, we humans have been forced to content ourselves with the knowledge that, despite living on a blue-white marble with seven billion other souls, a mere handful of our number—just 12—have traveled across the 240,000 miles (380,000 km) cislunar gulf to walk on the dusty surface of the Moon. From Neil Armstrong’s “one small step” to Buzz Aldrin’s “magnificent desolation” and from Pete Conrad’s “Whoopie” to Jack Schmitt singing about his stroll on the Moon, it is hard to imagine that almost a half-century has passed since human voices last crackled back to Earth from our closest celestial neighbor. And 45 years ago, this month, only days after the triumphant return of the Apollo 15 crew, the names of the last human explorers to visit the Moon for at least the next two human generations were announced to the world.

In truth, their identities should have been obvious. From the dawn of the Apollo era, Deke Slayton—the unflown Project Mercury astronaut, then serving as head of the Flight Crew Operations Directorate at the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC) in Houston, Texas—had followed an unofficial “crew rotation,” whereby a backup crew for a given mission would rotate into the prime crew, three flights down the road. For instance, astronauts Tom Stafford, John Young, and Gene Cernan backed up the Apollo 7 mission and went on to serve as the prime crew for Apollo 10 in May 1969, which executed a full dress-rehearsal of humanity’s first piloted lunar landing.

That should have meant that the crew of Apollo 17, the 20th century’s last manned mission to the Moon, would have been one and the same as the Apollo 14 backup crew. To be fair, Slayton himself admitted that once the first lunar landing had been accomplished, he felt able to step away from the crew rotation system. “I didn’t feel any obligation,” he wrote in his memoir, Deke, co-authored with Mike Cassutt, “technical or moral, to keep [the rotation system] in place.” With longer training templates for the later Apollo crews stretching to more than a year, as opposed to six months for Armstrong and Aldrin, there was greater scope for flexibility.

However, the crew rotation system was loosely followed. On 6 August 1969, shortly after his return from Apollo 10, NASA officially named Gene Cernan as backup commander of Apollo 14. This mission, originally targeted for July 1970, was subjected to extensive delay in the aftermath of the Apollo 13 near-disaster and did not ultimately take place until early 1971. Together with his crew of Command Module Pilot (CMP) Ron Evans and Lunar Module Pilot (LMP) Joe Engle, Cernan could be forgiven for anticipating their names to appear on the prime crew roster for Apollo 17, then scheduled for the fall of 1972.

Sadly, as history has shown, it was not to be. At least, not entirely.

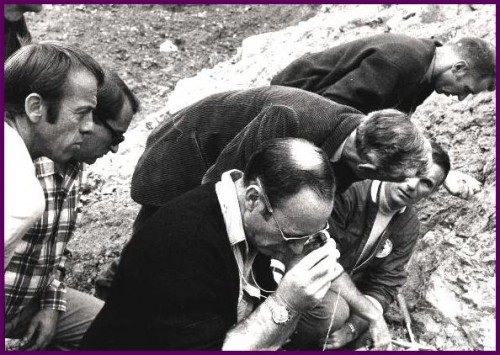

From the very outset, NASA had found itself embroiled in fierce debate with the scientific community over the need to send a professional geologist to the Moon on one of the Apollo missions. Only one member of the astronaut corps held the required credentials: geologist Dr. Harrison “Jack” Schmitt, selected by NASA in mid-1965, who had worked steadily on the development of the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP), as well as lunar module systems, instruments, and tools. Schmitt had single-handedly developed a lunar science program for astronaut Bill Anders on Apollo 8, and he worked extensively on improving the field geology skills of the early lunar explorers.

It paid off on 26 March 1970, when Schmitt was assigned—alongside Commander Dick Gordon and CMP Vance Brand—to the backup crew of Apollo 15. This might then lead to a prime crew selection for Apollo 18, although NASA reported that the trio would “be eligible for selection as prime crewmen for any mission subsequent to Apollo 16.” The significance of Schmitt’s presence on a crew was not lost. “Schmitt … is the first scientist-astronaut to be named to a flight crew,” NASA’s news release continued. “It is likely that he will be a prime crewman on Apollo 17 or 18. Since Dr. Schmitt is the only professional geologist currently qualified for flight crew selection, lunar landing site selection will be an important factor in determining which mission he will fly.”

Another factor was the steadily dwindling number of Apollo lunar landing missions on the manifest radar. As outlined in a previous pair of AmericaSpace history articles—available here and here—NASA initially contracted for the production of enough Saturn V and Apollo hardware to run the program through Apollo 20. However, budget cuts under President Richard M. Nixon’s administration prompted the agency to delete Apollo 20 from the manifest on 4 January 1970. Following the near-loss of Apollo 13, the Washington Post noted that up to four more missions (Apollo 16 through 19) might also face the budgetary ax. After much House and Senate debate, NASA received an allocation of $3.269 billion for Fiscal Year (FY) 1971, which required Administrator Tom Paine to cut Project Apollo’s budget by $42.1 million to a total of $914.4 million. In mid-July 1970, NASA also announced plans to cut its workforce by 900 personnel by October, producing the space agency’s lowest workforce level for seven years.

The possibilities for the twilight of Apollo were stark. One option included stretching out the schedule for four of the six remaining lunar missions—14 through 17—between January 1971 and the fall of 1972, followed by a break to conduct three long-duration Skylab flights in low-Earth orbit, then wrapping up the Moon landing program with Apollos 18 and 19 in 1974. Another proposed canceling Apollos 18 and 19 and making their hardware “available for possible future uses,” including a post-Skylab space station.

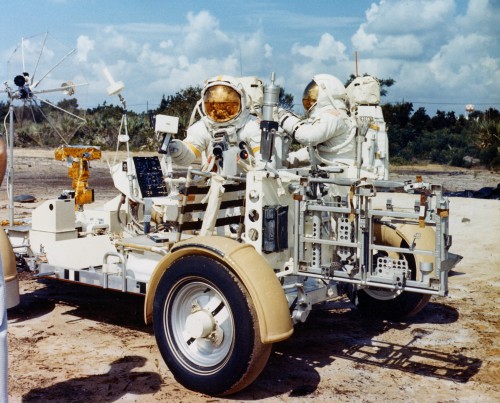

At length, on 2 September 1970, Paine announced the cancelation of Apollos 15 and 19, which would have respectively been the last of the “H-series” and “J-series” landing missions. The former involved a short-duration Lunar Module (LM), 33 hours on the surface and two Moonwalks, each lasting about four hours, whilst the latter encompassed a long-duration LM, up to three days on the surface and three Moonwalks, each running to six or seven hours. Additionally, J-series missions would benefit from a battery-powered Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV) and a Command and Service Module (CSM) equipped with an expansive Scientific Instrument Module bay (SIMbay) of research hardware.

After the cancelation, the remaining missions were renumbered. Apollo 14 became the last H-series mission and the newly renumbered Apollos 15, 16, and 17 formed the “new” J-series. However, the two “lost” missions would be popularly (but incorrectly) remembered as Apollos 18 and 19.

And with Apollo 18 officially gone, so too, it seemed, was Jack Schmitt’s opportunity to visit the Moon. Following the cancelation, Cernan, Evans, and Engle continued training as backups to the Apollo 14 crew and Gordon, Brand, and Schmitt pressed on with their preparations for the Apollo 15 backup role. Both backup crews, however, kept a keen eye on the prime slot for the final scheduled lunar landing mission, Apollo 17, which by this point had slipped until no sooner than December 1972.

Both were acutely accomplished. The commanders, Cernan and Gordon, had both flown two previous missions apiece, including flights to lunar orbit. In December 1970, the stature of Cernan, Evans, and Engle—as well as Schmitt—was raised when they were awarded NASA’s Superior Achievement Award for their efforts in the safe return of the Apollo 13 crew. For both crews, 1971 would be the year of truth in terms of which would secure the prime crew slot on the coveted final lunar landing mission.

The second part of this article will appear tomorrow.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

One Comment

One Ping

Pingback:‘An Even Better Friend’: 45 Years Since the Apollo 17 Decision (Part 2) « AmericaSpace