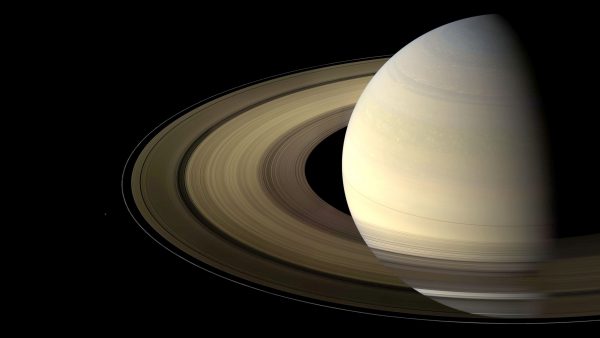

The Cassini mission to Saturn has been one of the most successful planetary missions ever, revealing the ringed giant and its moons as never before. Sadly, that mission is scheduled to end Sept. 15, 2017, and in preparation the spacecraft will be making some never-done-before maneuvers as it gets ready to take the final plunge into Saturn’s atmosphere on that date, aka the Grand Finale. Next week, Cassini will perform one of these feats, flying just past the edge of Saturn’s main rings.

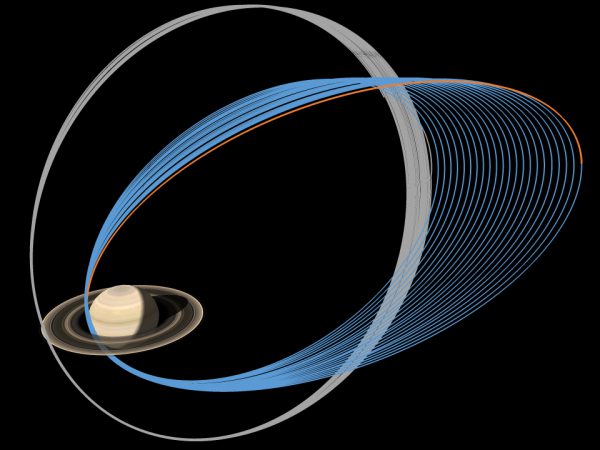

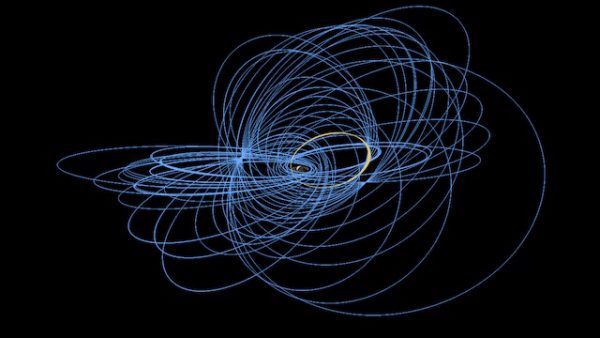

These close passes by the rings are called “Ring-Grazing Orbits,” during which Cassini will come within 56,000 miles (90,000 km) of Saturn itself. Cassini will also use the gravitational pull of Titan to help do this, by passing close to the large moon. Titan’s gravity can affect the spacecraft’s direction and speed as it moves in closer to Saturn. The closest pass by the edge of the rings will occur Nov. 29, when Cassini will enter an orbit which is closer to perpendicular with respect to Saturn’s equator and rings. By doing this, Cassini can get very close to the edge of the rings, which until now has never done before. The spacecraft will even pass through the dusty edges of the F ring, outside of the other larger main rings (A and B rings). This new vantage point will let mission scientists see details in the rings not visible before.

“We’re calling this phase of the mission Cassini’s Ring-Grazing Orbits, because we’ll be skimming past the outer edge of the rings,” said Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif. “In addition, we have two instruments that can sample particles and gases as we cross the ringplane, so in a sense Cassini is also ‘grazing’ on the rings.”

“Even though we’re flying closer to the F ring than we ever have, we’ll still be more than 4,850 miles (7,800 kilometers) distant. There’s very little concern over dust hazard at that range,” said Earl Maize, Cassini project manager at JPL.

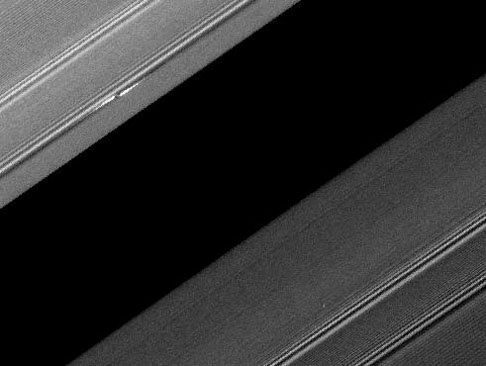

The F ring is usually considered to be the outermost ring, as it marks the boundary of the main ring system. There are, however, other rings which are much fainter and lie much farther out. The F ring is also unique in terms of its structure, containing bright streamers, wispy filaments, and dark channels that appear and develop over periods of only hours. Compared to the other main rings, it is also quite narrow, only about 500 miles (800 kilometers) wide. There is a denser region inside the ring which is about 30 miles (50 kilometers) wide. The F ring also has two tiny “shepherd” moons called Prometheus and Pandora, which orbit inside and outside the ring respectively.

So what other science observations will Cassini make during this flyby?

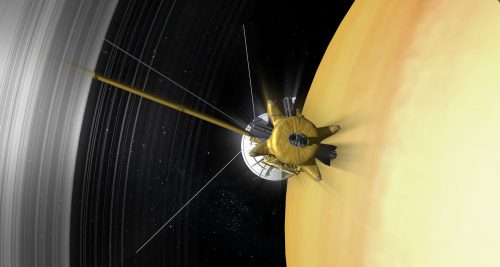

It will be able to “taste” the rings for the first time, from the inside out as it were, by sampling the faint gases surrounding the rings. It will do the same for the tiny particles which make up the F ring.

In December, Cassini will image the entire width of the main rings, resolving details as small as 0.6 mile (1 kilometer) per pixel. Cassini will obtain high-resolution images of the unusual “propellers” in the A ring which are associated with tiny unseen moonlets. The propeller features are up to several thousand miles (kilometers) long and several miles (kilometers) wide. With better images, scientists can learn more about their evolution and structure. Some of them have been named after famous aviators, such as Earhart. There are estimated to be dozens of them and 11 of them were imaged multiple times between 2005 to 2009.

“Propellers give us unexpected insight into the larger objects in the rings,” said Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. “Cassini will have the opportunity to watch the evolution of these objects and to figure out why their orbits are changing.”

“Observing the motions of these disk-embedded objects provides a rare opportunity to gauge how the planets grew from, and interacted with, the disk of material surrounding the early Sun,” said Carolyn Porco, Cassini imaging team lead based at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colo. “It allows us a glimpse into how the Solar System ended up looking the way it does.”

Cassini will also be able to see the tiny moons Atlas, Pan, Daphnis, and Pandora better than before. These little moons orbit near the outer edges of the main rings.

Cassini’s Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer will make a nine-hour movie of Saturn’s north pole, the location of the famous “hexagon,” and other instruments will measure the boundaries of Saturn’s upper atmosphere; future orbits will send Cassini skimming directly through the outermost reaches of the atmosphere for sampling.

NASA/JPL

In March 2017, Cassini will observe the rings backlit by the Sun, something never possible from Earth. Scientists would like to see small clouds of dust ejected by meteor impacts.

The next planned maneuver is in April 2017; at that time Cassini will pass through the 1,500-mile (2,400-kilometer) gap between Saturn and its main rings, something also not done before. It will pass as close as 1,012 miles (1,628 kilometers) above the cloud tops as it dives repeatedly through the narrow gap between Saturn and its rings. The first Ring-Grazing Orbit begins on Nov. 30 with a ring plane crossing five days later on Dec. 4. This will be repeated 20 times, with only about a week between each ring-plane crossing. Also on Dec. 4, Cassini will perform a brief burn of its main engine to help fine-tune the orbit and set the correct course for the remainder of the mission and the Grand Finale.

“This will be the 183rd and last currently planned firing of our main engine. Although we could still decide to use the engine again, the plan is to complete the remaining maneuvers using thrusters,” said Maize.

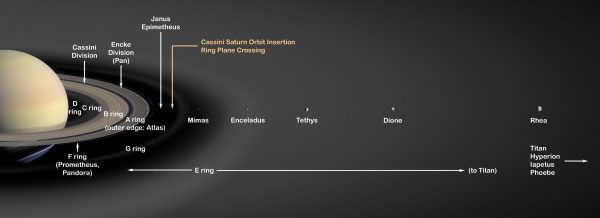

The material in Saturn’s ring is composed primarily of ice particles, ranging in size from microns to tens of meters. The main rings (A, B, and C) are less than 300 feet (100 meters) thick in most places, compared to their width of 38,600 miles (62,120 kilometers). The main rings are much younger than the rest of the Solar System, estimated to be only a few hundred million years old. The rings are named in order of their discovery; from the planet outward, they are D, C, B, A, F, G, and E.

Cassini has been orbiting Saturn since 2004 and has revolutionized our understanding of the giant planet and its moons. The mission will end next year, however, due to the spacecraft running low on fuel. Cassini will plunge into Saturn’s atmosphere, on purpose, to avoid any possibility of it colliding with any of the moons, in particular Titan or Enceladus, and contaminating them with any microbes which may happen to still be aboard the spacecraft.

Titan has lakes, seas, rivers, and rain of liquid methane with many geological similarities to Earth, but much, much colder. There are also vast sand dunes and “rocks” composed of extremely hard water ice and methane fog. The surface is perpetually shrouded in a thick haze, and Cassini was the first spacecraft to peer through it with radar and see the surface in detail.

Enceladus has a subsurface global ocean of water beneath its icy crust, much like Jupiter’s moon Europa. Huge plumes of water vapor erupt from cracks in the surface at the south pole. Analysis by Cassini’s instruments shows they contain water vapor, ice particles, salts, and a variety of organics. There is also evidence for hydrothermal activity on the ocean floor, just like on Earth; with water, heat, and chemical nutrients, Enceladus is now thought to be one of the best places in the Solar System to look for evidence of life beyond Earth.

These and many other discoveries make the Saturn system one of the most active and exciting places to explore in the Solar System. The moons alone are so diverse that the system has been referred to as a “mini-Solar System,” as has the Jupiter system. There isn’t another Cassini-style mission in the works yet, but there are plans for future missions back to Enceladus and Titan. Cassini has unveiled worlds like never seen before, and even after the mission ends the data sent back will continue to be analyzed for many years to come.

A “quick reference guide” for all of the upcoming Ring-Grazing Orbits is available here.

More information about the Cassini mission is available here.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

A testament to mankind’s determination to explore and find out “what’s there.” Remarkable!