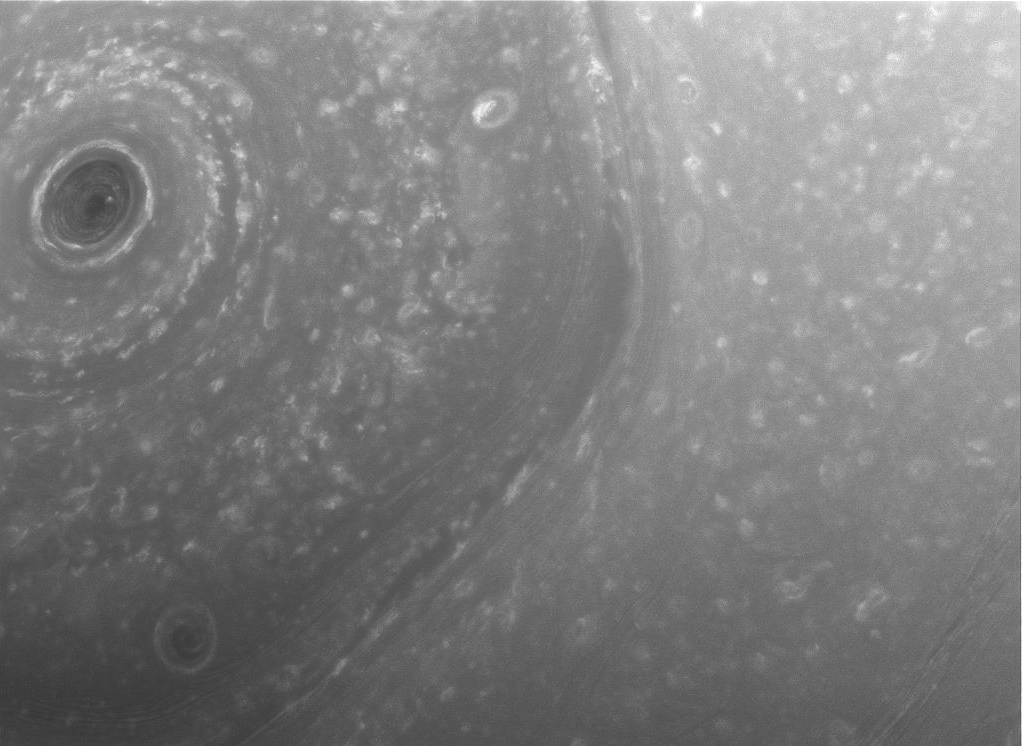

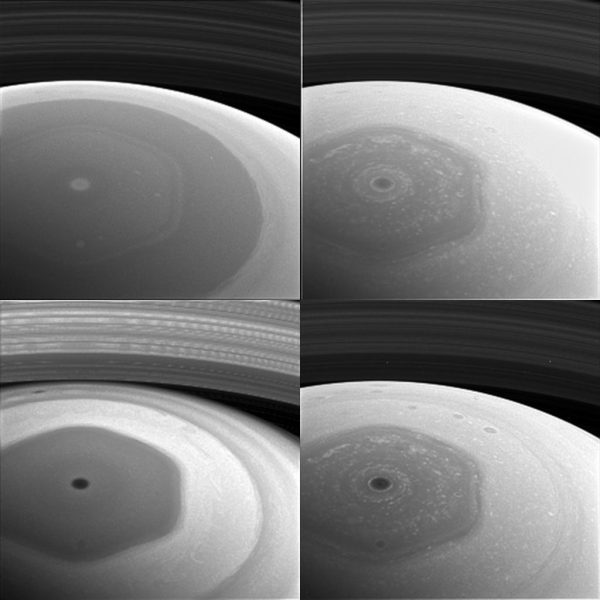

The Cassini spacecraft has successfully completed its first close pass of Saturn’s ring system, part of the Ring-Grazing Orbits phase of its mission, NASA said yesterday. As might be expected, Cassini has sent back some spectacular new images; these first images show Saturn’s northern hemisphere in incredible detail, including the famous “hexagon” jet stream surrounding the north pole.

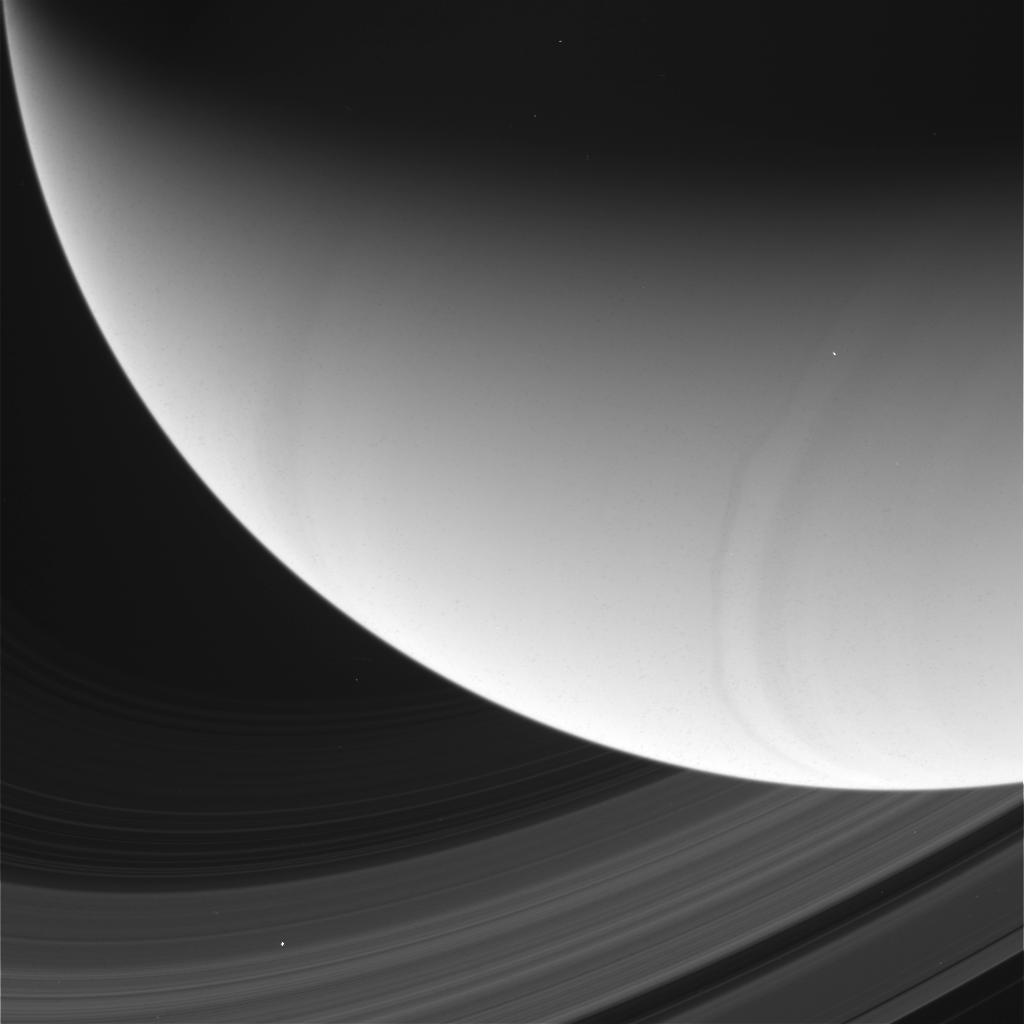

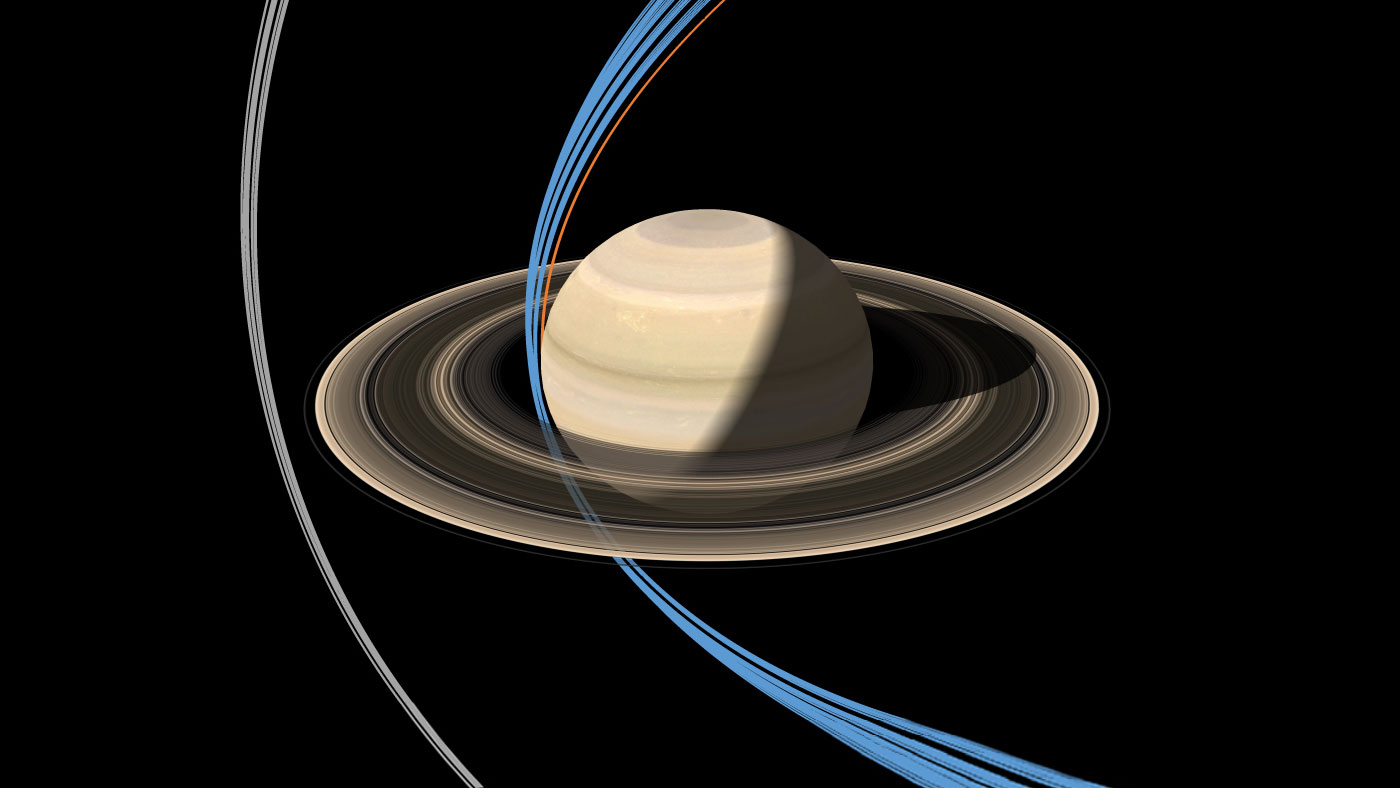

The Ring-Grazing Orbits phase of the mission actually began Nov. 30, and will consist of 20 week-long orbits which pass very close to the outer edges of Saturn’s rings. In each pass, the spacecraft also passes over the northern hemisphere just before “grazing” the rings. Subsequent passes will bring Cassini even closer to the edges of the rings, providing some of the closest images of the rings and the tiny moons which also orbit in that region.

“This is it, the beginning of the end of our historic exploration of Saturn. Let these images – and those to come – remind you that we’ve lived a bold and daring adventure around the Solar System’s most magnificent planet,” said Carolyn Porco, Cassini imaging team lead at Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colo.

“We’re calling this phase of the mission Cassini’s Ring-Grazing Orbits, because we’ll be skimming past the outer edge of the rings,” said Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. “In addition, we have two instruments that can sample particles and gases as we cross the ringplane, so in a sense Cassini is also ‘grazing’ on the rings.”

This first close pass of the rings occurred Dec. 4 at 5:09 a.m. PST (8:09 a.m. EST), at a distance of approximately 57,000 miles (91,000 kilometers) above Saturn’s cloud tops. About one hour previous, Cassini performed a short burn of its main engine for about six seconds. The spacecraft closed its engine cover about half an hour later for protection as it approached the ring plane.

“With this small adjustment to the spacecraft’s trajectory, we’re in excellent shape to make the most of this new phase of the mission,” said Earl Maize, Cassini project manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

“It’s taken years of planning, but now that we’re finally here, the whole Cassini team is excited to begin studying the data that come from these ring-grazing orbits,” said Spilker. “This is a remarkable time in what’s already been a thrilling journey.”

The Ring-Grazing Orbits, in turn, are leading up to the Grand Finale phase of the mission, which will conclude with Cassini plunging into the atmosphere (on purpose) on Sept. 15, 2017, when it runs out of fuel. During the descent, Cassini will analyze the atmosphere until the signal is finally lost. It will be the end of an astounding mission which began in 2004. The fiery ending to Cassini was decided upon in order to prevent the spacecraft from possibly colliding with any of the moons, in particular Enceladus or Titan, where contamination could occur from possible microbes still alive onboard.

The next close pass of Saturn’s rings will occur Dec. 11, and these orbits will continue until April 22, 2017. After that, during the Grand Finale phase, Cassini will plunge through the rings 22 times, through the 1,500-mile-wide (2,400-kilometer) gap between Saturn and its innermost ring, starting April 26.

Cassini will fly much closer to the edge of the outer F ring than it has previously, but mission scientists are confident that Cassini will be safe.

“Even though we’re flying closer to the F ring than we ever have, we’ll still be more than 4,850 miles (7,800 kilometers) distant. There’s very little concern over dust hazard at that range,” said Maize.

The F ring is the outermost ring of the main ring system and is unique in terms of its structure, containing bright streamers, wispy filaments, and dark channels that appear and develop over periods of only hours. It is also quite narrow, only about 500 miles (800 kilometers) wide, with a denser region inside the ring which is about 30 miles (50 kilometers) wide. The F ring also has two tiny “shepherd” moons called Prometheus and Pandora, which orbit just inside and outside the ring respectively.

Although the mission is coming closer to ending, there is still a lot of science to be done by Cassini. The spacecraft recently just made two more close flybys, of the moons Enceladus and Titan. Cassini flew past Titan on Nov. 29, the second-to-last ever flyby of Titan before Cassini enters the Grand Finale phase of its mission. During the flyby, called T-125, Cassini collected images of the moon’s Xanadu, Hotei Arcus, and Menrva regions with the Visible and Infrared Spectrometer (VIMS). From the update:

“Flyby T-125 has two primary goals: Mapmaking of Titan’s surface, and changing Cassini’s orbit to begin what is perhaps the boldest and most thrilling segment of Cassini’s nearly 20-year mission.”

About halfway through the flyby, Cassini switched to using its Composite Infrared Spectrometer (CIRS) instrument, which will be used, for the last time, to take temperature measurements of Titan’s surface, creating a temperature map. Cassini will then use the moon’s gravity to help move it into position for the Ring-Grazing Orbits later on. Cassini will then be in an elliptical orbit inclined about 60 degrees from Saturn’s ring plane.

Cassini revealed Titan to be one of the most fascinating places in the Solar System, with lakes, seas, rivers, and rain of liquid methane/ethane, mountains of water ice, ancient nitrogen rivers, methane fog, and vast “sand dunes” composed of hydrocarbons. Its geological processes mimic those of Earth, but in a much colder environment. Titan is also now thought to have a subsurface ocean of water where temperatures are warmer.

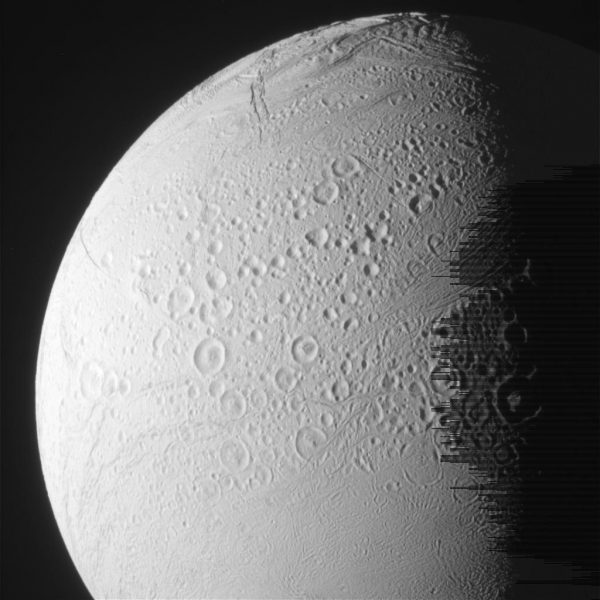

Cassini also made another close pass of Enceladus on Nov. 27, and although not as close as some previous flybys, Cassini still sent back amazing images. Like Titan and some other moons such as Europa, Enceladus is now known to have a subsurface ocean of water beneath its icy crust. On Enceladus, however, the water from that ocean can make its way to the surface, where it erupts in huge plumes or geysers through cracks in the ice at the south pole. It is a very unique world as well, and it is now thought that the ocean could very well be habitable, at least for microorganisms. There is evidence from Cassini for hydrothermal activity on the ocean bottom, which could provide heat and nutrients, just like on Earth. Direct analysis of Enceladus’ plumes has found a variety of organics as well; while not proof of life yet, they are an intriguing discovery.

“Cassini’s legacy of discoveries in the Saturn system is profound,” Spilker said. “We’ll continue observing Enceladus and its remarkable activity for the remainder of our precious time at Saturn. But these three encounters will be our last chance to see this fascinating world up close for many years to come.”

Cassini’s last close flyby of Enceladus was on Dec. 19, 2015, at a distance of 3,106 miles (4,999 kilometers). Cassini performed an even closer flyby on Oct. 28, 2015, passing only about 30 miles (49 kilometers) above the surface. This was the last chance for Cassini to sample the plumes by flying directly through them. While providing valuable clues about the ocean, determining just how habitable it may be, or searching for life itself, will require follow-up missions, such as Life Investigation For Enceladus (LIFE).

Saturn itself is a massive gas giant planet with winds and cyclones in its atmosphere that dwarf any ever seen on Earth both in speed and size. And then there’s that hexagon-shaped jet stream around the north pole, unique in the Solar System. Back in 2014, Cassini may also have witnessed the birth of a tiny moonlet within Saturn’s rings. Such discoveries again show how the Saturn system is an active, dynamic, and changing place. What else might Cassini find as it flys closer to and within the rings and over the atmosphere in the coming months?

Cassini’s mission at Saturn may be winding down, but it’s not over yet. There is still a lot of science to be done, and the views from so close to, and inside, the rings should be like none ever seen by any spacecraft before. The rings of Saturn alone have evoked curiosity and wonder for centuries; what would the astronomers back then say now if they could see what Cassini has discovered? Could anyone have predicted such a wild plethora of worlds were waiting to be found?

More information about the Cassini mission is available here and the Ring-Grazing Orbits specifically here.

Be sure to “LIKE” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Instagram & Twitter!

.

Forthose of us old enough to remember the Mariner 4 Mars flyby in July 1965 and the then-tantalizing crude pictures of Mars, the Cassini images are simply astounding! Wow!

Yep!

And thank you Paul Scott Anderson!

Now when are folks going to start building some big and extremely capable Orion nuclear pulse spaceships on the Moon to get us to Saturn and beyond?

Time will tell, but it is getting a bit old waiting and waiting…

Patience is a virtue.