With a naval officer in command of the International Space Station (ISS), it might have seemed obvious that New Year’s Day 2001 would carry a corresponding nautical tradition. Expedition 1 Commander Bill Shepherd of NASA and his Russian crewmates, Sergei Krikalev and Yuri Gidzenko, rang in the start of what would turn out to be one of the United States’ darkest years with private family conferences and an awareness that a busy few weeks lay ahead. The infant station had just received its first massive set of power-producing solar arrays and in mid-January it was expected that the STS-98 shuttle crew would deliver the Destiny lab.

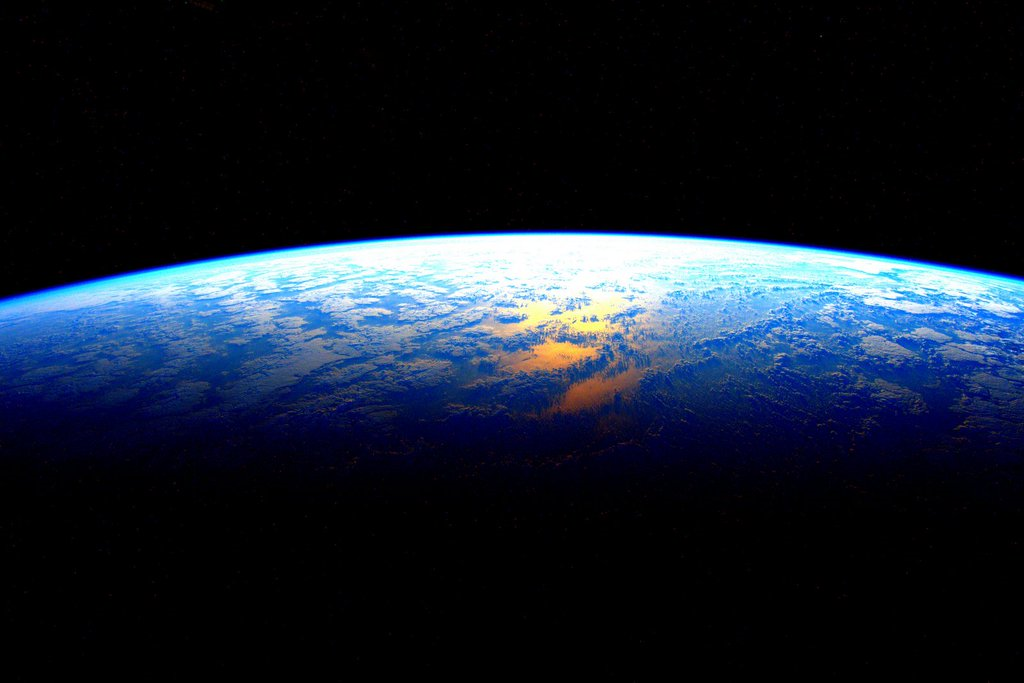

Spending New Year in orbit is nothing new; since the voyage of Skylab 4 in 1973-74, the transition has been celebrated by Americans and Russians, Japanese and Italians, Dutchmen and Canadians, and, last year, also by a Briton. And the 2017 New Year sees a Frenchman, for the first time, in orbit to witness the festivities. All have passed the time quietly, watching the Home Planet for a glimpse of fireworks and marveling at the accomplishments of one year and sharing hope for the promise of the next.

As 2001 began, Shepherd honored his military heritage by sharing a poem about his ten-weeks-and-counting experience aboard the station. “In long-standing naval tradition,” he explained, “the first entry in a ship’s log for the New Year is always recorded in prose.” And without further ado, he waxed lyrical about his crew’s journey, “orbiting high above Earth … traveling our destined journey beyond realm of sea voyage or flight.” Shepherd wrote about ringing in a new era as Earth itself revolved, “counting the last thousand years done,” for 1 January 2001—although the second year of a new decade—actually marked the official start of the 21st century. Then Shepherd added an interesting observation to his piece: “Fifteen midnights to this night in orbit; a clockwork not of earthly pace.” For as he and Krikalev and Gidzenko circled the globe at 17,500 mph (28,100 km/h), they passed through numerous terrestrial time zones and “saw” numerous New Years.

For Shepherd, being in this “new age and place” on such a significant date carried a juxtaposition of the romance and adventure of the past and the scientific and technological possibilities of the future. As he watched “screens dancing shapes in pale glow / We guide her course by electronic pulse” and acknowledged the important role played by his ship’s solar panels and stabilizing gyroscopes, he could not escape from the reality that this had few of the navigational devices of old.

“On this ship’s deck,” Shepherd wrote, “sits no helm now / Rudder, sheet and rigs long since gone / but here still—a pull to go places / Beyond lines where sky meets the dawn.” Still, his prose was laced with traces of older times: Though star trackers mark Altair and Vega, same as mariners eyed long ago, we are still as wayfinders of knowledge, seeking new things that mankind shall know.

Of course, the station runs on Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) and Shepherd and his men had their own “official” instant of midnight and the dawn of the New Year, but the peculiarity of their position aroused much fascination back on Earth. In spite of their on-board clocks, they exchanged earlier greetings with mission controllers in Moscow (at GMT+3 hours) and later ones with Houston (at GMT-6 hours).

Shepherd’s Expedition 1 crew was by no means the first team of spacefarers to see in the New Year from beyond the veil of Earth. Back in 1973-74, the astronauts of the final Skylab mission—Commander Gerry Carr, Science Pilot Ed Gibson, and Pilot Bill Pogue—were six weeks into their 84-day voyage when they endured (rather than enjoyed) the passage of one year into the next. The first part of their flight had left them excessively overworked and exhausted, and on 28 December 1973 Carr had been obliged to engage in a heart-to-heart with Mission Control. Two days later, it was agreed that routine chores would be placed on a so-called “shopping list,” to be completed when time permitted, and the crew were to be left unhassled during meal times and undisturbed after dinner in the evening. At around the same time, on the 29th, Carr and Gibson performed an EVA to collect micrometeoroid samples and photograph Comet Kohoutek, which was visible in Earth’s skies that winter.

Unfortunately, Kohoutek did not live up to its media billing as the “Comet of the Century,” but the spacewalkers were impressed. “We observed a gorgeous thing,” recalled Carr in a NASA oral history, “small, faint, but gorgeous.” Today, a handful of pencil sketches by Gibson are enshrined in the Smithsonian. On the ground, the excitement was not so intense among the general public. Journalists started calling Kohoutek the “Flop of the Century,” ignoring with typical mass-media cynicism the scientific yield and focusing only on its brightness as a marker of significance. But in reality, the fault lay fairly and squarely upon their own shoulders; for it was the media which treated Kohoutek as a sure thing, a dead cert, right from the outset. In March 1974, Sky & Telescope glumly told its readers that, whilst professional astronomers were jubilant with their observations, “the general public wondered what had happened to the spectacle promised by the news media.”

Over the years, several Soviet and Russian crews spent New Year in orbit. Yuri Romanenko and Georgi Grechko celebrated the dawn of 1978 aboard the Salyut 6 space station, as did Vladimir Titov and Musa Manarov from the Mir outpost in 1988. From then onward, every New Year until 1999 would see at least two humans in orbit on Mir, including a female cosmonaut—Yelena Kondakova—together with Germany’s Thomas Reiter and a pair of NASA astronauts, John Blaha and Dave Wolf. With no one in space at the dawn of 2000, there followed a resumption of activity from 2001 to the present day, aboard the multi-national ISS.

Of the 1990s, little detail has emerged about how the transition from one year to the next was celebrated, although the dawn of 1998 was marked by a failure of Mir’s motion control system computer. During the recovery process, the entire station—save for the base block and the Kvant-1 astrophysics module—was powered down as a electrical conservation measure. With the departure of Mir’s second-to-last crew in August 1999, the station was left unoccupied for the transition into 2000, and it was Bill Shepherd’s Expedition 1 team who celebrated the next New Year, high above Earth.

Since then, each 1 January has seen at least two spacefarers circling the Home Planet. Expedition 4 crewmen Yuri Onufrienko, Carl Walz, and Dan Bursch enjoyed a serene New Year in 2002, relaxing and communicating with family and friends, whilst Expedition 6’s Ken Bowersox, Nikolai Budarin, and Don Pettit saw the dawn of 2003 during their official sleep shift. “The first day of the New Year,” noted a NASA press release, “involved only a few routine maintenance tasks, exercise and time off for the crew.” Exactly a month later, on 1 February, Space Shuttle Columbia was lost with its entire crew during re-entry and NASA was thrust into one of the worst crises in its half-century of existence. Although the ISS would continue to be occupied, thanks to the assured crew return capability offered by Russia’s Soyuz craft, the outpost would host only a skeleton staff of two men, each remaining aboard for rotating six-month tours. By New Year’s Day 2004, the resumption of shuttle operations in the wake of the disaster was in sight, but a long and tortured road remained before the ISS could be completed.

The second part of this article will appear tomorrow.

Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace