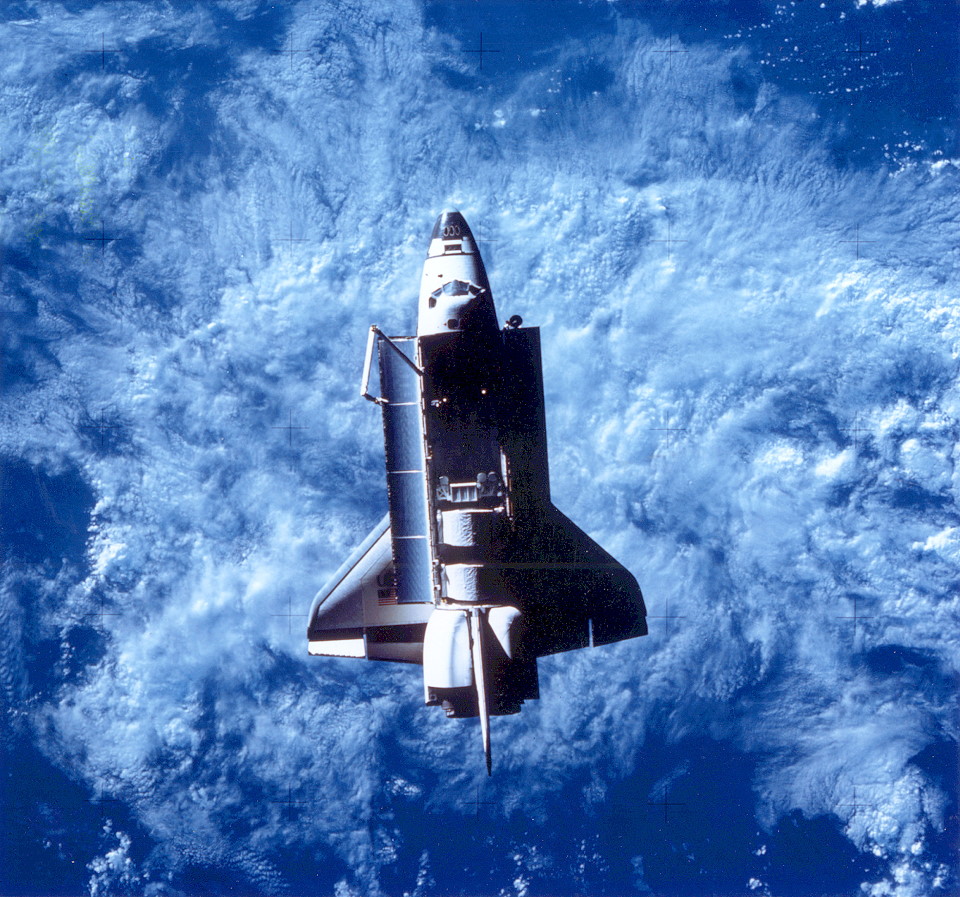

Thirty-five years ago, this week, America launched its first woman into space. Physicist Dr. Sally Ride rocketed into orbit aboard shuttle Challenger—accompanied by fellow STS-7 astronauts Bob Crippen, Rick Hauck, John Fabian and Norm Thagard—and became the third female spacefarer, following in the footsteps of Soviet cosmonauts Valentina Tereshkova and Svetlana Savitskaya. STS-7 marked the first time that five people had launched into space on the same vehicle and, during their six days aloft, the crew deployed two communications and released and later retrieved the German-built Shuttle Pallet Satellite (SPAS), which returned the first “full” photographs of the shuttle, drifting serenely above the Home Planet.

Ride, who was selected as part of NASA’s first class of shuttle astronauts, had been told of her assignment to STS-7 in private by George W.S. Abbey, head of Flight Crew Operations, and Johnson Space Center (JSC) Director Chris Kraft. In a NASA oral history interview, Ride—who died in 2012—recalled their conversation, in which it was noted that a great deal of media attention would fall on her shoulders. Kraft’s message, she remembered, was that they would offer her all the support she needed. “It was a very reassuring message,” Ride said later, “coming from the head of the space center.” Crippen, Hauck, Fabian and Ride were formally named in April 1982, with Thagard joining them a few months later.

Years later, Hauck recalled a few “awkward” occasions, including training on the shuttle’s toilet, whilst some NASA engineers convinced themselves that Ride might need a makeup kit. “So they came to me, figuring that I could give them advice,” Ride laughed. “It was about the last thing in the world that I wanted to be spending my time training on, so I didn’t spend much time on it at all.”

By early 1983, the STS-7 launch date had slipped from late spring to early summer and on the morning of 18 June the astronauts departed the Operations & Checkout (O&C) Building at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida, bound for Pad 39A and the shuttle. When they reached the pad, Crippen turned to his crewmates and told them that they had just said goodbye to the last sane people in the facility, “because we’ve got to be crazy to do what we’re doing!” Their countdown proceeded smoothly and at 11:33 a.m. EDT Challenger rose from Earth to begin her second mission into space. This was fortuitous, for the deployment “windows” of Canada’s Anik-C2 and Indonesia’s Palapa-B1 communications were so short that only five minutes were available to launch on 18 June.

“Physically, the simulator does a pretty good job,” Ride said of its closeness to the real thing. “It shakes about right and the sound level is about right and the sensation of being on your back is right. It can’t simulate the G-forces that you feel, but that’s not too dramatic on a shuttle launch. The physical sensations are pretty close and, of course, the details of what you see in the cockpit are very realistic. The simulator is the same as the shuttle cockpit and what you see on the computer screens is what you’d see in flight.” There, however, the similarities ended. “The actual experience of a launch is not even close to the simulators,” Ride exclaimed. “The simulators just don’t capture the psychological and emotional feelings that come along with the actual launch. Those are fuelled by the realisation that you’re not in a simulator—you’re sitting on top of tons of rocket fuel and it’s basically exploding underneath you! It’s an emotionally and psychologically overwhelming experience; very exhilarating and terrifying, all at the same time.”

Over the following days, Fabian and Ride oversaw the deployment of their two commercial satellite payloads. For her part, Ride found that—after an hour or so to learn how to move around in the strange environment—weightlessness was very relaxing. During the second half of STS-7, the crew used the Remote Manipulator System (RMS) arm to deploy and later retrieve SPAS, whose cameras captured the first full view of a shuttle in space. In addition this historic photograph, another historic view was getting the RMS into a configuration that created the number “7” to honor their mission.

This was not originally intended, even though the crew had trained to maneuver the arm on the ground and their mission patch included the “7” configuration as part of its design. Still, some engineers were concerned that it would stretch the arm to its structural limits. “We worked out the position [with] the arm in the shape of a ‘seven’ for the seventh flight and we didn’t tell anybody about this, of course. We had this on a back-of-our-hand-type of procedure—what angles each joint had to be in order for it to look like that—and then we had worked on the timing, so that we could catch the space shuttle against the black sky, with the horizon down below. That was the picture we most wanted. Now, we got a lot of good pictures, against the cloud background and against the total black sky…It had just a whole battery of cameras: a still camera, a TV camera, a motion-picture camera and so we’re running these various cameras by remote as we fly the shuttle around it so that we can get the shuttle in various types of positions.”

Capturing the SPAS after a couple of days, Challenger demonstrated the shuttle’s capacity for rendezvous and cleared a significant hurdle, ahead of the planned 1984 retrieval and repair of NASA’s Solar Max satellite. “It was a big deal,” Bob Crippen remembered later, “and we wanted to make sure that we could rendezvous with satellites, could come back in and grab them. It turned out that it all went extremely well.

All in all, STS-7’s six days in orbit ran smoothly. One of the worrisome problems was a small “pit” in one of the shuttle’s forward flight deck windows, caused by an impacting fragment of debris, probably a paint fleck, moving a 4 miles (6.4 km) per second. Crippen elected to say nothing to the ground and the issue did not receive attention until after Challenger was back on the ground.

Landing on 24 June was originally targeted to mark the shuttle’s first return to the specially-constructed runway at KSC, but poor weather forced a wave-off to the backup site at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. This gave the astronauts a few hours of free time to perform their own in-space Olympics, in which Ride—by default—won the distinction as the fastest woman on the crew.

Ride’s accomplishment in becoming the first U.S. woman in space was magnified a year later, in October 1984, when she flew again. A third mission was on the cards, but the loss of Challenger in early 1986 marked the end of her astronaut career. Since her flight, 45 further American women have followed in her footsteps—including Expedition 56’s Serena Auñón-Chancellor, who arrived aboard the International Space Station (ISS) a few days ago—and secured a raft of achievements for the United States. Kathy Sullivan became the first female U.S. spacewalker, Shannon Lucid the first U.S. woman to fly a long-duration mission to a space station, Eileen Collins the first woman to pilot and command the shuttle and Peggy Whitson the first woman to command a space station. Others, sadly, died whilst reaching for the stars: Ride’s classmate, Judy Resnik, aboard Challenger’s final flight, together with Laurel Clark and Kalpana Chawla aboard STS-107.

The human space program for women has changed markedly since Ride’s flight, 35 summers ago. Whilst the early shuttle-era astronaut classes included a mere handful of women astronauts, the two most recent groups—selected in June 2013 and last year—have seen women fill about half of their ranks. It is an indicator, perhaps, that the importance of U.S. women in space continues to grow.

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook!

.

Strange there hasn’t been an all-female crew. Could happen if Russia’s only female cosmonaut gets to fly with NASA female astronaut and either ESA’s Samantha Cristoforetti or Canada’s Jenni Sidey.

Had the Soviet Voskhod series not ended after Leonov’s space walk on March 23, 1965, there were tentative plans for an all-female crew.

*correction:Leonov’s space walk took place on March 18, 1965. Gemini 3 launched on March 23, 1965.