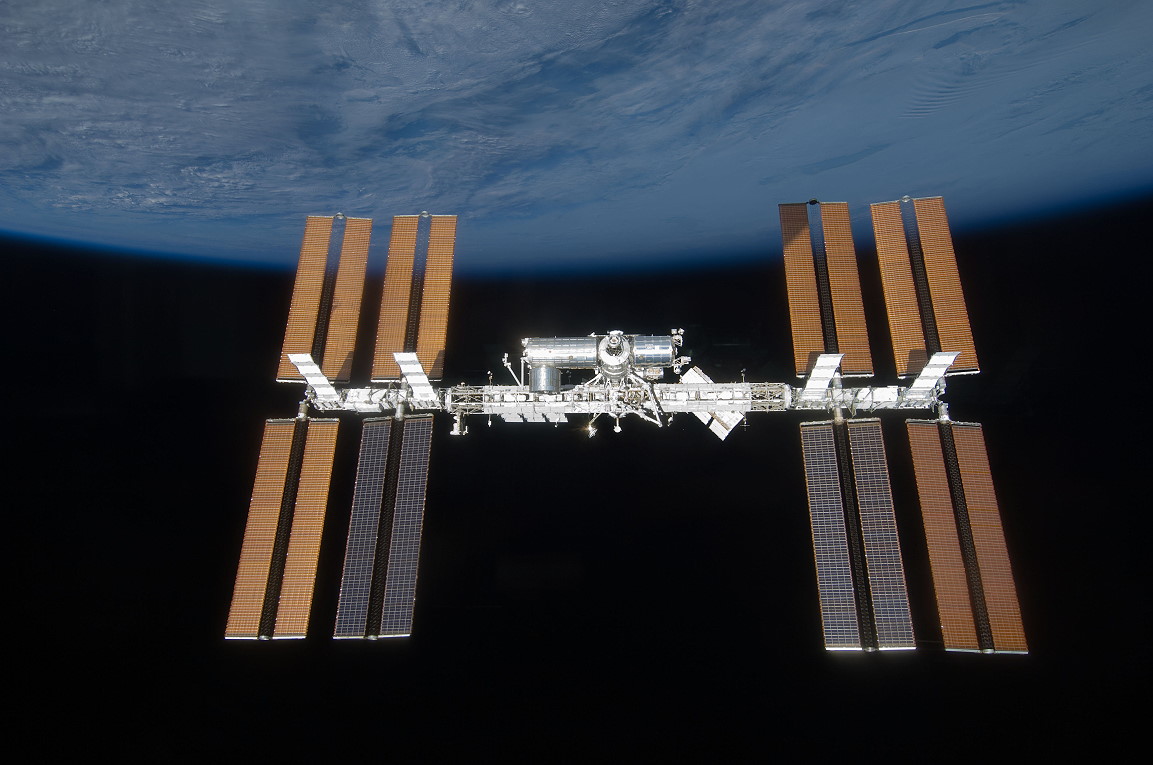

Ten years ago, this month, the crew of shuttle Discovery roared to orbit and achieved—in the words of Kennedy Space Center (KSC) launch commentator Candrea Thomas—“full power for full science” aboard the International Space Station (ISS), by delivering the fourth and final set of U.S.-built solar arrays, batteries and radiators to the sprawling orbital outpost. During their 13 days in space, STS-119 Commander Lee “Bru” Archambault and his crew supported extensive robotics, three sessions of Extravehicular Activity (EVA) and rotated long-duration crew members aboard the ISS, bringing NASA veteran Sandy Magnus home after four months and dropping off Koichi Wakata to become the first Japanese astronaut to fly a long-duration space station mission.

Yet STS-119 had changed significantly in character over the years. Originally planned to occur much sooner in the ISS assembly sequence, ahead of the delivery of the U.S. Harmony node and Japan’s Kibo and Europe’s Columbus labs, it found itself shifted downstream in the reshuffling of shuttle missions and ISS priorities following the Columbia tragedy. In December 2002—seven weeks before STS-107 was lost during re-entry—NASA announced a four-man “core” crew for STS-119, then targeted to fly in January 2004 aboard shuttle Atlantis.

Commander Steve Lindsey, Pilot Mark Kelly and Mission Specialists Mike Gernhardt and Carlos Noriega would support up to three EVAs to install the S-6 segment onto the farthest point of the station’s starboard truss. They would also deliver the Expedition 9 crew of Russian cosmonauts Gennadi Padalka and Oleg Kononenko, together with U.S. astronaut Mike Fincke, and bring home the Expedition 8 crew of U.S. veterans Mike Foale and Bill McArthur and seasoned Russian flyer Valeri Tokarev.

Video Credit: National Space Society

Following Columbia’s loss, all shuttle launches were indefinitely suspended and most crews were disbanded. In December 2003, Lindsey, Kelly and Noriega were reassigned to STS-121, intended as the second Return to Flight (RTF) test-mission to evaluate new technologies and techniques for inspecting and repairing the shuttle’s heat shield.

Several months later, Noriega was removed from the crew for medical reasons, and left the astronaut corps in January 2005. By this time, their original STS-119 flight had moved further to the right, with both the European and Japanese space agencies desiring more time to utilize their respective pressurized labs before the retirement of the shuttle program.

Eventually, in October 2007, a wholly-new STS-119 crew was announced. Commander Lee “Bru” Archambault was an obvious selection, having piloted a similar truss-delivery mission on STS-117 a few months earlier. Joining him was his STS-117 crewmate Steve Swanson—“a real honor to fly with him a second time”—together with Tony Antonelli, long-duration ISS veteran John Phillips and former schoolteachers-turned-astronauts Joe Acaba and Ricky Arnold. The six-man core crew would deliver Koichi Wakata to the ISS and bring home Sandy Magnus, forming a seven-strong team for both ascent and descent.

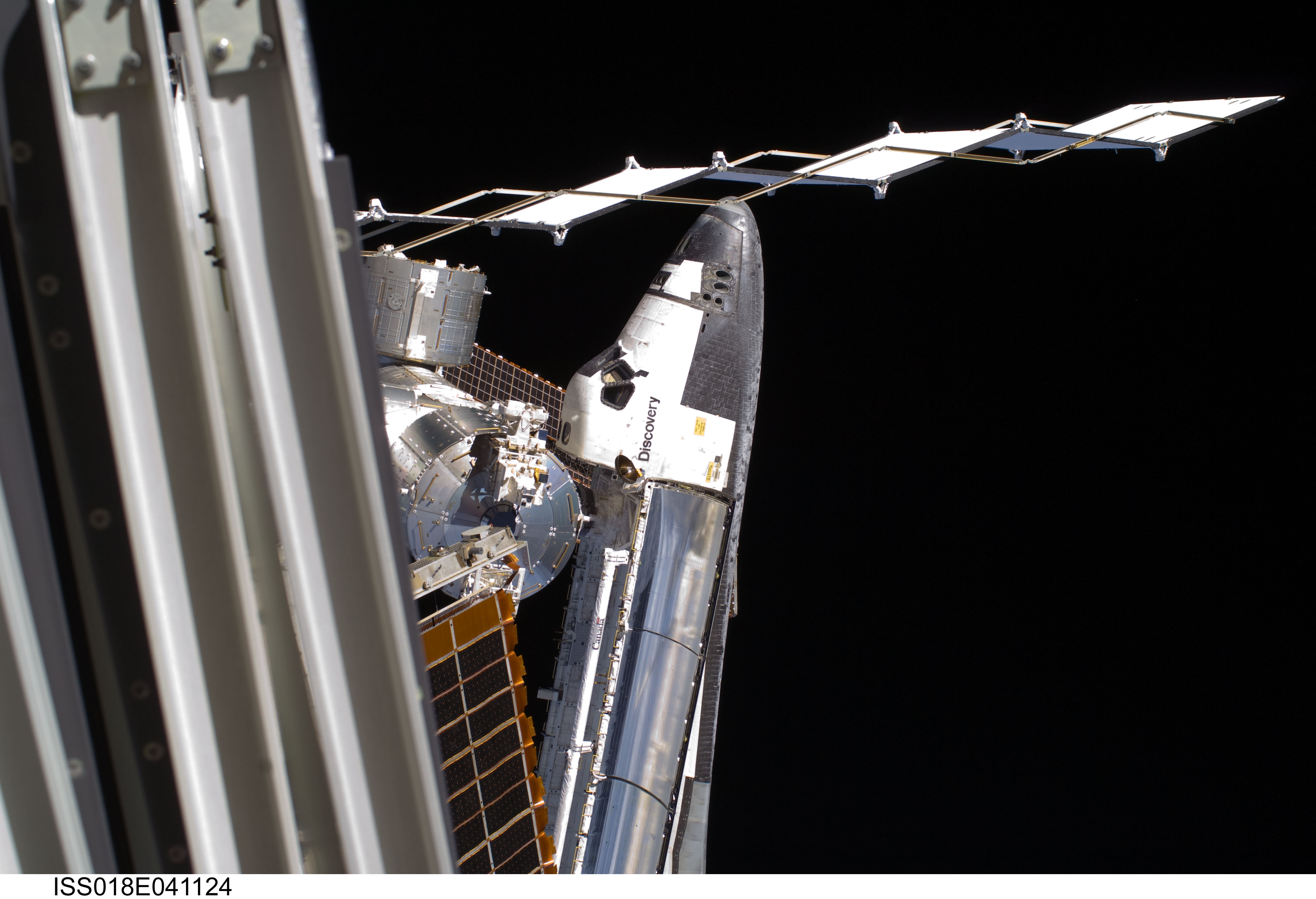

Launch of STS-119 was originally slated for the fall of 2008, but delays to preceding shuttle missions pushed the manifest inexorably to the right and Archambault’s crew found themselves targeted to fly in early-mid February 2009. However, following the Flight Readiness Review (FRR) in January, managers opted to undertake additional analysis and particle-impact testing of flow control valves on the shuttle’s three main engines, following damage observed during a previous mission in late 2008. The valves were replaced and following a scrubbed launch attempt on 11 March, Archambault and his men roared away from historic Pad 39A at 7:43 p.m. EDT on the 15th.

The launch—and particularly the instant of Main Engine Cutoff (MECO)—was met with great joy by Sandy Magnus, who was seen whooping and punching the air in a televised view aboard the space station. “Sandy never really believed we were gonna get there until that moment,” Archambault mused at the post-flight press conference. Over the first two days of the mission, the astronauts checked out their space suits, inspected Discovery’s wing leading edges and heat shield for damage and prepared tools and equipment for rendezvous and docking.

Archambault performed a smooth link-up with the ISS at 5:20 p.m. EDT on 17 March, as both space vehicles soared high above Western Australia. A couple of hours later, hatches were opened and the STS-119 astronauts boarded the station, to be greeted with great enthusiasm by Magnus and her Expedition 18 crewmates Mike Fincke and Yuri Lonchakov. After a safety briefing, Swanson, Acaba and Arnold began moving their space suits from the shuttle into the Quest airlock, whilst Lonchakov helped Wakata to install his custom-molded seat liner into the Soyuz spacecraft.

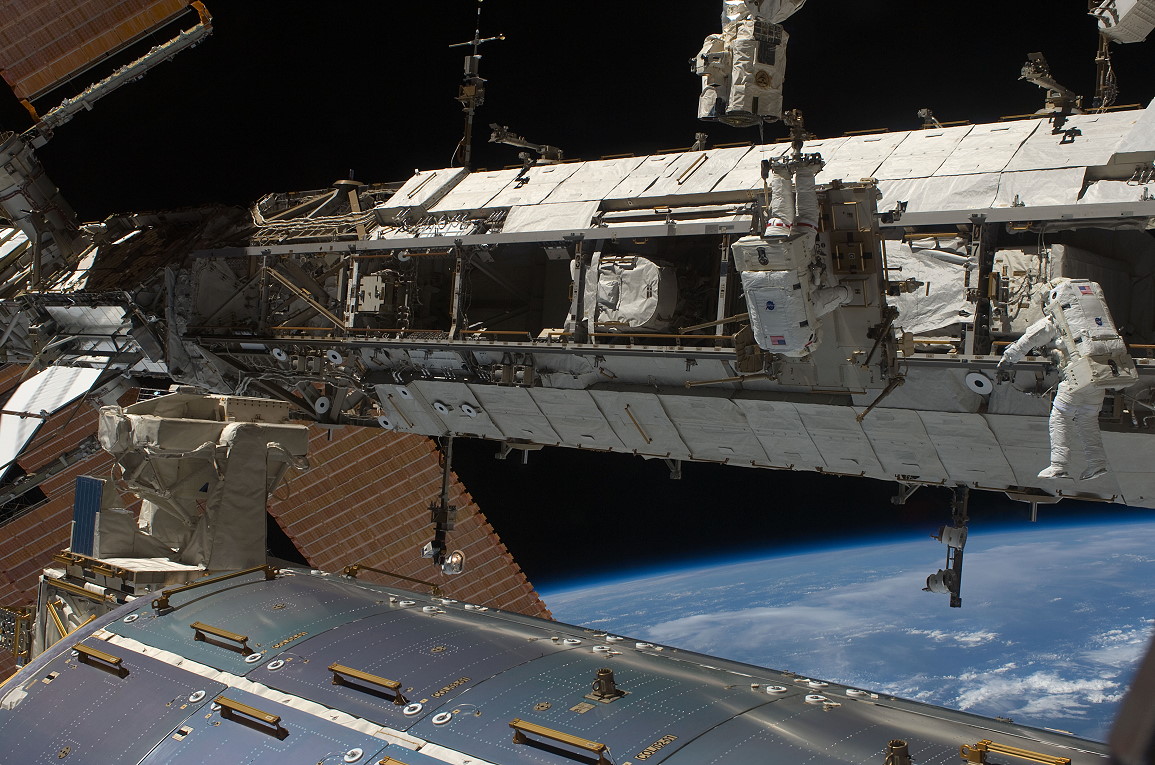

Installation of the 31,000-pound (14,000 kg) S-6 truss segment required astronauts working the controls of both Discovery’s Remote Manipulator System (RMS) mechanical arm and the space station’s own Canadarm2. With Antonelli and Acaba on the shuttle side and Phillips and Magnus on the station side, Canadarm2 grappled the gigantic S-6 and plucked it from Discovery’s payload bay and “overnight-park” positioned it for installation early on 20 March. Swanson and Arnold floated out of the Quest airlock and provided guidance to Phillips and Wakata, as they maneuvered S-6 into place at the outboard tip of the starboard truss. When S-6 was in place, the spacewalkers removed launch restraints and established power and data connections, before returning to the airlock after six hours and seven minutes.

Next morning, with Phillips’ finger hovering over the abort switch in case he needed to halt the process, the S-6’s two solar arrays were successfully deployed, bringing the total surface area across a total of four pairs of U.S.-provided “wings” to almost an acre. The second EVA, performed by Swanson and Acaba and lasting 6.5 hours, saw the spacewalkers working to prepare a location on the port side of the truss for a future battery replacement, then installing an unpressurized cargo carrier attachment mechanism on the P-3 segment, a Global Positioning System (GPS) antenna on the pressurized logistics module of Japan’s Kibo facility and completing other miscellaneous tasks. STS-119’s third and final spacewalk, by Acaba and Arnold, saw them relocating one of two crew equipment carts from one side of the Mobile Transporter (MT) to the other and lubricating the end-effector capture snares on Canadarm2. All told, the three EVAs totaled 19 hours and four minutes.

With their mission objectives triumphantly concluded, a farewell ceremony on the morning of 25 March provided an opportunity for the two crews to part company. At 2 p.m. EDT, hatches between Discovery and the ISS were closed and the shuttle undocked from the complex a little under two hours later. Antonelli took the controls for a fly-around inspection of the station, before departing the vicinity.

A late inspection of Discovery’s thermal-protection system was conducted and Archambault guided his ship to a smooth touchdown on the Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF) at Kennedy at 3:14 p.m. EDT on 28 March. In bringing the ISS to full power for full science, STS-119 also proved a critical step in enabling the expansion of expedition crew strength from three to six permanent residents. And only eight weeks after Discovery’s wheels kissed the concrete at KSC, the first six-person long-duration crew was on-orbit to usher in a new decade of unparalleled science.