For almost two decades, the Fourth of July—that most quintessential day of celebration in the United States—has seen at least one American citizen off the planet, aboard the International Space Station (ISS). This year, astronauts Drew Feustel, Ricky Arnold and Serena Auñón-Chancellor will observe the 242nd anniversary of the Declaration of Independence from their orbital perch, 250 miles (400 km) above Earth. Yet before the era of continuous ISS habitation, several shuttle crews and Mir residents spent the holiday aloft and in two cases, in 1982 and 2006, astronauts landed and launched on the day itself.

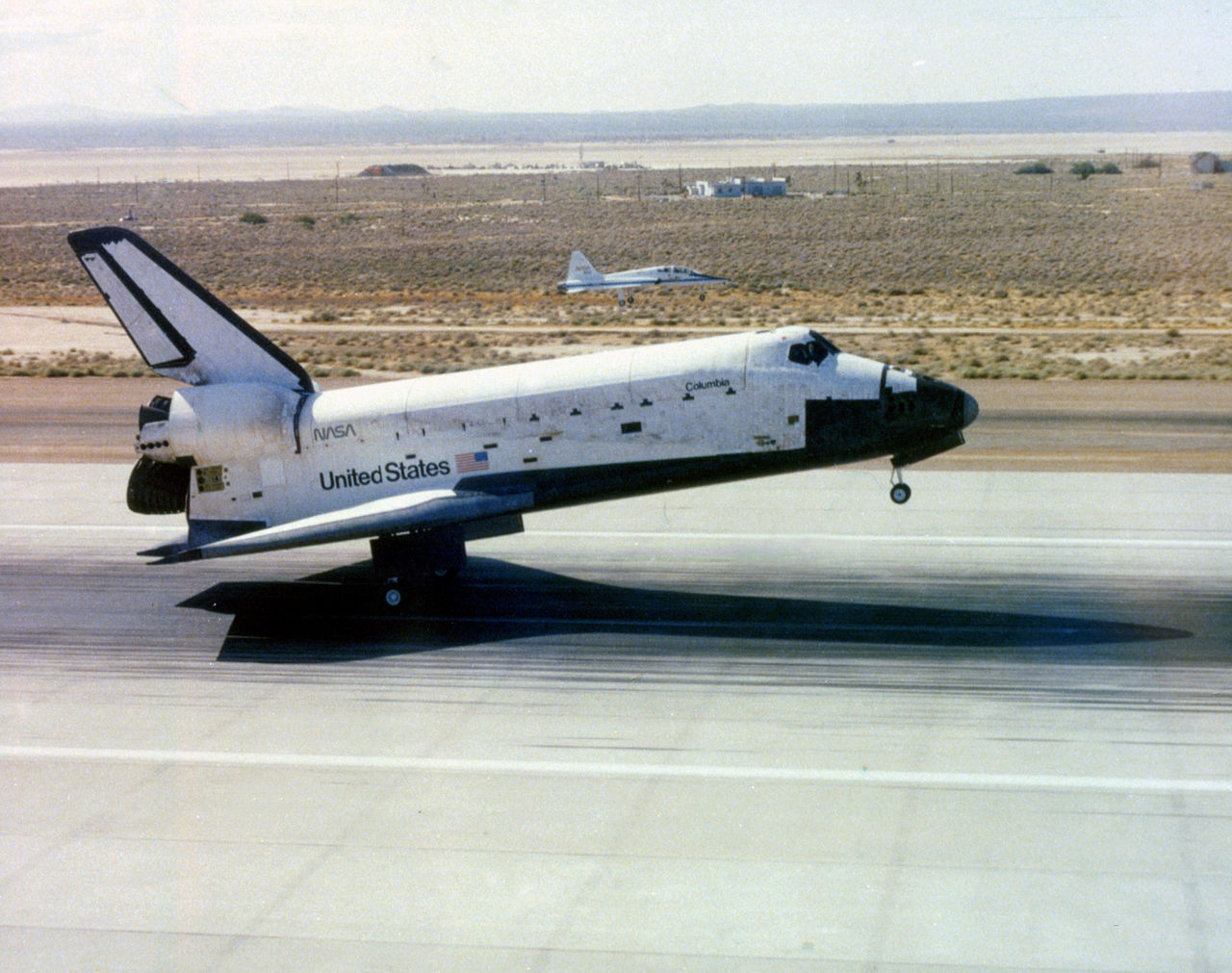

Early on 4 July 1982, a rapidly-moving black-and-white speck appeared on the horizon at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., bringing STS-4 crewmen Ken Mattingly and Hank Hartsfield back home. The first Independence Day spent in orbit by U.S. astronauts began in a rather comical fashion. Mattingly and Hartsfield were in the process of packing away much of their research hardware, after seven days in orbit aboard shuttle Columbia. It had been a highly successful mission and the last of four Orbital Flight Tests (OFTs), before the shuttle was declared fully operational. Among the research performed by Mattingly and Hartsfield were the first classified payload, flown on behalf of the Department of Defense.

“On one experiment, they had a classified checklist [and] because we didn’t have a secure comm link, we had the checklist divided up in sections that just had letter-names, like Bravo-Charlie, Tab-Charlie, Tab-Bravo, that they would call out,” recalled Hartsfield. Whenever the astronauts spoke to U.S. Air Force controllers at the Satellite Control Facility in Sunnyvale, Calif., they would be told, for example, to ‘do Tab-Charlie.’ We had a locker that we kept all the classified material, and it was padlocked, so once we got on orbit, we unlocked it and did what we had to do.” As the end of the mission neared, Hartsfield packed away the remainder of the classified materials and secured the locker.

He told Mattingly. “I got all the classified stuff put away. It’s all locked up.”

“Great!” replied Mattingly.

Half an hour later, the Mission Control Center (MCC) at the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas, called and told them that the military staff at Sunnyvale wanted to talk to them. The Air Force controller asked them to “do Tab-November”. The two astronauts looked at each other, bewildered. What the hell was Tab-November? Neither of them could remember. The secretive nature of the instruction and the lack of a secure communications link also meant they could not ask over the radio. The only option was to reopen the classified locker, dig through all the materials, and find the checklist. Eventually, after much searching, Hartsfield finally found the glossary entry for Tab-November.

It read: Put everything away and secure it!

Shortly afterwards, the STS-4 crew commenced their hypersonic descent back through the “sensible” atmosphere, bound for Edwards. Their arrival in the California desert was being watched closely by President Ronald Reagan and First Lady Nancy Reagan, and Mattingly and Hartsfield had already been briefed by NASA Administrator Jim Beggs and asked to think of some memorable words to mark the occasion. “We knew they had hyped-up the STS-4 mission, so that they wanted to make sure we landed on the Fourth of July,” Mattingly recalled in his NASA oral history. “It was in no uncertain terms that we were going to land on the Fourth of July, no matter what day we took off. Even if it was the Fifth, we were going to land on the Fourth! That meant, if you didn’t do any of your test mission, that’s okay, as long as you land on the Fourth…because the President is going to be there. We thought that was kinda interesting!”

Fortunately, Columbia’s landing occurred precisely on time on Independence Day, wrapping up a textbook flight. Now came Mattingly’s biggest challenge: How to welcome the Reagans inside the shuttle. He and Hartsfield considered putting up a notice, worded to the effect of Welcome to Columbia: Thirty minutes ago, this was in space.

Immediately after wheelstop, he turned to Hartsfield. “I am not going to have somebody come up here and pull me outta this chair! I’m going to give every ounce of strength I’ve got and get up on my own!” Previous crews had come back to Earth, some feeling fine, others feeling nauseous, and still others required a gurney to carry them off the spacecraft for medical attention. That would not happen with the president in attendance. Mentally and physically set up to meet the chief, Mattingly pushed himself upward out of his seat…and smashed his head sharply on the overhead instrument panel!

“Oh, did I have a headache,” he recalled later.

“That’s very graceful,” Hartsfield quipped.

Nevertheless, the two returning space heroes composed themselves and Mattingly wiped away the few spots of blood. In the few minutes before Columbia’s hatch was opened, they walked around the middeck, to get themselves acclimated, before descending the steps to meet Reagan. Hartsfield—well known for his humor—was on top form that day. “Well, let’s see. If you do it like you did gettin’ out of your chair, you’ll go down the stairs and you’re going to fall down, so you need to have something to say,” he told Mattingly. “Why don’t you just look up at the president and say ‘Mr. President, those are beautiful shoes?’ Think you can get that right?”

By 4 July 2006, the shuttle program had changed considerably, with 114 missions behind it and a pair of accidents, which had resulted in the loss of 14 astronauts. Yet launching shuttle Discovery that afternoon—the first, and only, time to date that a U.S. piloted orbital space vehicle has launched on Independence Day—followed a process well-trodden over the preceding 25 years. The shuttle’s three main engines roared to life, producing a noticeable “twang” effect, as the vehicle structurally flexed upward, ahead of the ignition of the twin Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs).

“And liftoff of the Space Shuttle Discovery,” came the call, as six American astronauts and one German spacefarer speared into a crystal clear Florida sky, “returning to the space station, paving the way for future missions beyond.” It was 2:37:55 p.m. EDT. Aboard the orbiter were Commander Steve Lindsey—who went on to serve as chief of NASA’s astronaut office and led Discovery’s final mission—and crewmates Mark Kelly, Mike Fossum, Lisa Nowak, Piers Sellers, Stephanie Wilson and Thomas Reiter. Bound for a 12-day logistics and resupply mission to the International Space Station (ISS), Lindsey’s crew would drop off Reiter for a half-year increment aboard the orbital lab. In doing so, Reiter would become the first European astronaut to embark on a long-duration voyage to the ISS.

The morning had begun with some confusion for Lindsey. Departing the Operations & Checkout (O&C) Building at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC), the seven astronauts had waved their respective national flags for the gathered press and wellwishers. With so many red, yellow and black flags around, Lindsey was not sure if it was the German Fourth of July. Launching on this quintessential U.S. holiday, though, occurred primarily by happenstance. Discovery’s two previous launch attempts on 1 and 2 July had both been scrubbed, leading to a 48-hour delay and, serendipitously, a third try on the 230th anniversary of the day that members of the Second Continental Congress had ratified the language of separation of the Thirteen Colonies from Great Britain.

“On the nation’s 230th birthday, Discovery rocketed into the Florida sky this afternoon,” NASA reported after the successful launch, noting that this was “the first human spacecraft to launch on an Independence Day holiday.”

It was a remarkable achievement and yet numerous other shuttle crews had also spent the day in orbit. Following Mattingly and Hartsfield’s landing in 1982, five more shuttle crews observed the holiday from their orbital perch, beginning with STS-50 in July 1992. Three years later, the crew of STS-71 undocked from Russia’s Mir space station on 4 July, wrapping up the first of nine rendezvous and docking flights between the two former foes. That morning, the STS-71 astronauts were awakened, unsurprisingly, to America the Beautiful, and a year later, in 1996, the crew of STS-78 were nearing the end of their record-setting 17-day mission on Independence Day.

Awakened by Bruce Springsteen’s Born in the USA and Lee Greenwood’s I’m Proud to Be an American, STS-78 Commander Tom Henricks noted that the U.S.-born crew members of this multi-national crew were proud to be Americans on the 220th anniversary of independence. Later that same day, Henricks showed his terrestrial audience a view of the United States from space, complete with patriotic background music, and paid particular tribute to 19 U.S. service personnel recently killed a few days earlier in the Khoban Towers bombing in Saudi Arabia. A further dozen months passed before another shuttle crew—that of STS-94, reflying the Microgravity Science Laboratory (MSL)-1—celebrated the historic date in orbit. The STS-94 astronauts were awakened on 4 July 1997 to the tune of Kate Smith’s God Bless America, as well as the news that NASA’s Sojourner rover had successfully touched down on the surface of Mars, becoming the first wheeled vehicle ever to land on the Red Planet.

For the last 17 years, of course, at least one U.S. citizen has always been in space on Independence Day, aboard the ISS. On 4 July 2001, NASA astronauts Jim Voss and Susan Helms were in residence aboard the fledgling space station as members of Expedition 2. “The Nation’s largest Independence Day celebration will be joined by visitors from outer space—not aliens, but NASA’s International Space Station crew,” it was reported, as the United States marked 225 years of political existence. “The two NASA members of the space station crew will send their “out of this world” birthday message, reflecting on the birth of America, during the Fourth of July gala concert beginning at 8 p.m. EDT from the West Lawn of the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C.”

The following Independence Days were times of triumph and sadness, as Expedition 5’s Peggy Whitson welcomed the holiday in 2002, followed—in the aftermath of the Columbia disaster—by Expedition 7’s Ed Lu in 2003. For Whitson and her crewmates, the day “was essentially a holiday in space…although they did some work off a generic task list”, whilst that of Lu and his companion, Russian cosmonaut Yuri Malenchenko, their schedule comprised “light activities interspersed with time off”. A year later, Expedition 9’s Mike Fincke and his Russian commander, Gennadi Padalka, enjoyed a three-day weekend to enjoy the holiday period, whilst the following Fourth of July fell just shy of the Return to Flight (RTF) of the shuttle fleet after the loss of Columbia. Aboard the ISS for the 2005 celebration was the Expedition 11 crew, including U.S. astronaut John Phillips, whilst the following year NASA’s Jeff Williams of Expedition 13 was watching via a monitor in the station’s Destiny laboratory as shuttle Discovery rocketed into orbit.

Subsequent years have seen increased crew sizes, from three to six, with U.S. astronauts Clay Anderson, Greg Chamitoff, Mike Barratt, Tracy Caldwell-Dyson, Doug Wheelock, Shannon Walker, Ron Garan, Mike Fossum, Joe Acaba, Chris Cassidy, Karen Nyberg, Steve Swanson, Reid Wiseman, Jack Fischer, Jeff Williams and Peggy Whitson (both on two occasions) and One-Year crewman Scott Kelly having celebrated Independence Day in orbit between 2007 and 2017. With Drew Feustel, Ricky Arnold and Serena Auñón-Chancellor aboard the station this year, it can be expected that a U.S. presence in space over the holidays will continue for several more years to come.