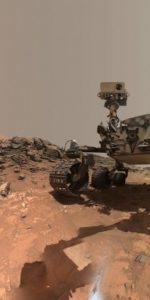

Dave Griggs, pictured during the Space Shuttle program’s first contingency spacewalk in April 1985, lost his life 30 years ago this month. Photo Credit: NASA

Thirty years ago, America’s Space Shuttle program had risen from the depths of despair—following the calamitous loss of Challenger—to a triumphant return-to-flight and the three surviving orbiters, Columbia, Discovery and Atlantis, were beginning to establish a tempo for a resumption of mission operations. In November 1988, two months after STS-26 finally laid Challenger’s ghosts to rest, several new shuttle crews were announced for the following year.

One of them, the crew of STS-33, included retired U.S. Navy Naval Air Reserve rear admiral Dave Griggs, who would the most senior military officer ever to fly aboard the shuttle. Griggs had flown once before and would be embarking on his first flight in the pilot’s seat, but only six months later, on 17 June 1989, he lost his life in a shocking tragedy that no one could possibly have foreseen and which altered the face of STS-33 forever.

STS-33 was the first nocturnal Shuttle launch and landing of the post-Challenger era; entirely appropriate, perhaps, in light of the shroud of darkness which covered its primary payload. Photo Credit: NASA

Labeled “a superb pilot” by fellow astronaut Jeff Hoffman, Griggs came from a naval aviation background and his stern, moustached countenance would not have been out of place in the portrait of a Civil War officer. Born in September 1939, he graduated from the Naval Academy and flew the A-4 Skyhawk on three overseas cruises to the Mediterranean and Vietnam, before attending Naval Test Pilot School at Patuxent River, Md. Griggs resigned from active duty in 1970, earned a master’s degree and joined NASA as a civilian research pilot, although he remained a naval reservist.

He served as project pilot and later head of the Shuttle Training Aircraft (STA) office, participating extensively in the design, development and testing of its systems. Selected as one of the first class of shuttle astronauts—the so-called “Thirty-Five New Guys” (TFNGs)—in January 1978, he had already accrued over 8,000 hours in high-performance jet aircraft, as well as flight instructor certification and over 300 carrier landings in more than 45 distinct aircraft. Even today, Griggs remains one of the most experienced pilots ever picked for astronaut training.

The “core” NASA crew of Mission 41F, scheduled for launch on 9 August 1984 for a seven-day flight. From left to right are Commander Karol “Bo” Bobko, Pilot Don Williams and Mission Specialists Dave Griggs, Rhea Seddon and Jeff Hoffman. Photo Credit: NASA, via Joachim Becker/SpaceFacts.de

He was selected for his first shuttle flight in September 1983. Originally slated for launch in the summer of 1984, it was extensively delayed and its payloads shuffled, before being canceled and the entire NASA crew—Commander Karol “Bo” Bobko, Pilot Don Williams and Mission Specialists Rhea Seddon, Jeff Hoffman and Griggs—shifted to another mission in early 1985. By an incredible stroke of cruel luck, that flight, too, was canceled, but only weeks later, on 12 April, Griggs and his fellows launched aboard shuttle Discovery on a seven-day flight which deployed two commercial communications satellites. Significantly, one of those satellites suffered a malfunction shortly after departing the payload bay and Hoffman and Griggs performed the first-ever “contingency” spacewalk of the shuttle program to effect makeshift repairs.

Griggs was listed as pilot of the Earth Observation Mission (EOM), scheduled for August 1986 but canceled following the tragic loss of Challenger at the start of that year. The entire astronaut corps effectively stood down as efforts got underway to bring the shuttle program back online and in November 1988 he was appointed as pilot for STS-33, then targeted to launch on 10 August 1989. Griggs would be joined by Commander Fred Gregory and Mission Specialists Manley “Sonny” Carter, Kathy Thornton and Story Musgrave. Their four-day flight would deploy a classified payload for the Department of Defense. However, by the early summer of 1989, changes to the shuttle flight manifest had pushed STS-33 into the fall, with an expected launch date no sooner than the second half of November.

Dave Griggs (at right), pictured with Jeff Hoffman during the shuttle program’s first “contingency” spacewalk in April 1985. Photo Credit: NASA

Early on 17 June, Griggs was preparing for a weekend air show in Clarksville, Ark., flying alone in a single-engine, 1940s-era AT-6 vintage airplane. Shortly after 9:10 a.m. CDT, according to eyewitnesses, he was performing aileron rolls, when one wing accidentally touched the ground and the aircraft crashed into a wheat field, just south of the town of Earle. “Griggs was flying for the McNeely Charter Service, a private air service based in Earle,” noted Arlington National Cemetery, where Griggs is buried. “The plane hit the ground in a field of wheat near the company’s hangars.”

As highlighted by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) in its July 1990 final report, an eyewitness saw Griggs’ aircraft approach McNeely Airport in Earle from the west, “low and slow”, as if preparing to land. “Then it was maneuvered to an inverted attitude over Runway 8 at 50-100 feet,” the NTSB report noted. “After remaining inverted for a short time, the aircraft was rolled back to an upright attitude. However, as the aircraft rolled upright, it angled to the right side of the runway, descended and crashed. The witness said the aircraft seemed to “slip” sideway as it rolled to the upright position, before crashing.”

Following Griggs’ passing, John Blaha (left) was selected to serve as STS-33’s replacement pilot. He joined fellow crewmates Sonny Carter, Story Musgrave, Kathy Thornton and, at far right, Commander Fred Gregory. Photo Credit: NASA

Tragically, Griggs lost his life in the accident, aged just 49. According to the NTSB, Griggs “had visited with a prominent AT-6 pilot and had expressed special interest in the AT-6 pilot’s routine involving inverted flight. The AT-6 pilot had provided info, but advised the astronaut against performing rolls in the AT-6 at low altitude.” The board found that the accident arose from improper planning and overconfidence, which resulted in the pilot’s loss of control, coupled with inadequate altitude and airspeed. It was a sad end for a skilled aviator who had, by 17 June 1989, accumulated an impressive 9,500 flying hours and might have gone on to command a Space Shuttle mission of his own.

Griggs’ passing sent shockwaves through the astronaut corps. In his memoir, Riding Rockets, veteran shuttle flyer Mike Mullane remembered seeing STS-33 astronaut Kathy Thornton—her cheeks soaked with tears—walk into Houston’s Outpost tavern after the funeral and numbly place a wreath of flowers onto the bar.

The official mission patch for STS-33, bearing the tiny gold star to honor Dave Griggs. Image Credit: NASA

However, amidst the tragedy, the harsh light of reality continued to glare. With STS-33 only months away, Griggs’ seat as second-in-command needed to be filled. A first-time shuttle pilot was undesirable at short notice, so veteran astronaut John Blaha—newly returned from piloting STS-29, earlier in the year—was slotted into the crew. He had already been assigned to a later flight, but his place was taken by “rookie” Sid Gutierrez.

According to Fred Gregory, it was his choice to pick Blaha. “I liked John,” he told an interviewer for CollectSpace.com in September 2011, and felt that his recent flight experience would make him an ideal fit.

For Gutierrez, the assignment came totally out of the blue. “We were not expecting any new assignments tobe announced for another month or so,” he told AmericaSpace’s Ben Evans in an email correspondence. “I did have some idea that I was getting close and I had reviewed the upcoming missions. It was summer and we headed off on an extended family vacation driving to the East Coast, visiting relatives in Ocean City and touring sites around D.C. We then planned to stay at a friend’s cabin in West Virginia before starting the drive home. It was the days before cell phones or even personal pagers, so I left my assistant with good phone numbers to reach me up until leaving the cabin in West Virginia. From there on back to Houston I told her we would just drive along and stop when and where we felt like it. So, there were a few days where she could not reach me.

The STS-40 crew, with Sid Gutierrez standing at far right. Photo Credit: NASA, via Joachim Becker/SpaceFacts.de

“While reading a paper in DC we learned of the tragic accident involving Dave,” Mr Gutierrez continued. “I thought briefly about the possibility of a funeral at Arlington but heard nothing. It did not cross my mind that his death would have an impact on my flight assignment. We got home on the weekend and slept in. Late in the morning I wondered out into the front yard to pick up the newspaper. My next-door neighbor was out doing something, and he said: “Congratulations.” I thought that he was being sarcastic and making a joke about making it through an extended family vacation driving across the country. I turned to him and said something about not yet being awake. He realized I had missed the point and added: “I was talking about your flight assignment.” I looked at him inquisitively and said: “What do you mean?” He said: “It is in the paper. Not that one. It is old news. It happened days ago.” He quickly realized I had no idea I had been assigned. He gave me some idea of what day it had occurred, and I went back in, rummaged through the pile of old papers and found the article where NASA announced my assignment. I told Marianne and she congratulated me. Of course, we were sad that it was a result of an unfortunate accident.

“I got a call from the STS-40 Commander Bryan O’Connor. He officially notified me I had been selected and explained how they had tried in vain toreach me. They planned to notify all the crew members before the official announcement, but they tried to reach me about half an hour after we had left the cabin. They called the owner of the cabin, who was a manager at NASA Headquarters, and he said: “Sid is gone. You missed him.” After being advised by my assistant that we were out of contact somewhere along the Skyline Drive, they went ahead with the official announcement.”

So it was that shortly after midnight on 23 November 1989, shuttle Discovery rose from historic Pad 39B at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida, bearing Gregory, Blaha, Carter, Musgrave and Thornton on their classified mission. Five days later, after a highly successful flight, Gregory and Blaha guided their ship to a smooth touchdown at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. But the memory and legacy of Dave Griggs was not to be forgotten. In fact, emblazoned on the STS-33 crew patch—alongside the surnames of his former crewmates and a stylized eagle of the United States—was a tiny gold star.

A gold star for an admiral.

.

.

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook and Twitter!

.

.

Tragedy followed STS-33 in 1991 when mission specialist Sonny Carter perished in a domestic airliner crash, not long after being assigned to STS-42.