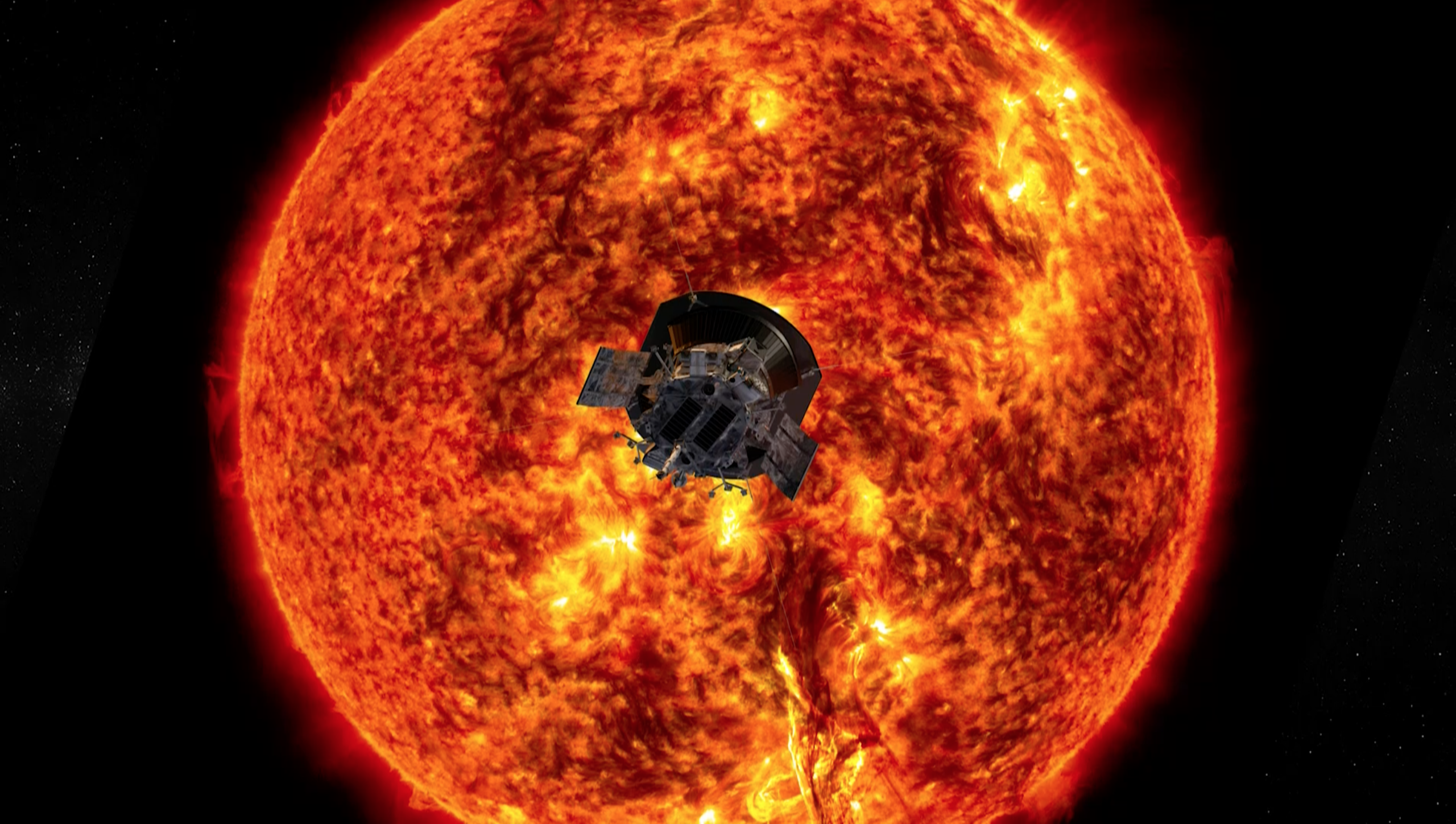

Thanks to NASA’s Parker Solar Probe (PSP), scientists are now learning more about the Sun than ever possible before. The newest findings were announced this morning during a media teleconference.

Four new science papers detailing these findings have just been published in the journal Nature.

These latest discoveries focus on particles and material that are ejected from the Sun, from the turbulent and rotating solar wind, as well as new evidence for a dust-free zone near the Sun and new data on space weather such as energetic particle storms and coronal mass ejections. They provide important clues as to how the sun behaves and the underlying physics involved. This not only helps scientists understand how the Sun formed and evolved, but also to better understand space weather such as particles from solar flares hitting our atmosphere.

“This first data from Parker reveals our star, the Sun, in new and surprising ways,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for science at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “Observing the Sun up close rather than from a much greater distance is giving us an unprecedented view into important solar phenomena and how they affect us on Earth, and gives us new insights relevant to the understanding of active stars across galaxies. It’s just the beginning of an incredibly exciting time for heliophysics with Parker at the vanguard of new discoveries.”

“The Sun has fascinated humanity for our entire existence,” said Nour E. Raouafi, project scientist for Parker Solar Probe at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, which built and manages the mission for NASA. “We’ve learned a great deal about our star in the past several decades, but we really needed a mission like Parker Solar Probe to go into the Sun’s atmosphere. It’s only there that we can really learn the details of these complex solar processes. And what we’ve learned in just these three solar orbits alone has changed a lot of what we know about the Sun.”

PSP has now completed the first three of 24 planned close flybys of the Sun, coming closer than any other spacecraft to date. The spacecraft has, for the first time, traveled through the Sun’s outer atmosphere, the corona.

First, the solar wind. PSP found that the solar wind – the continuous flow of plasma particles from the Sun – is even more active and complex than previously known. This is important to know, since by the time the solar wind reaches Earth, it has become more uniform, with only occasional turbulence. PSP was able to study the solar wind at only 15 million miles from the Sun.

“The complexity was mind-blowing when we first started looking at the data,” said Stuart Bale, the University of California, Berkeley, lead for Parker Solar Probe’s FIELDS instrument suite, which studies the scale and shape of electric and magnetic fields. “Now, I’ve gotten used to it. But when I show colleagues for the first time, they’re just blown away.”

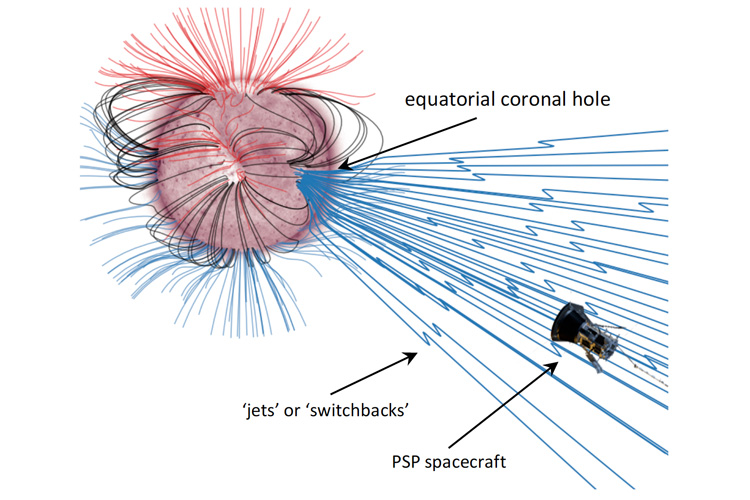

The FIELDS instruments on PSP analyzed the solar wind by measuring how the electric and magnetic fields around the spacecraft changed over time, along with measuring waves in the nearby plasma. The measurements revealed quick reversals in the Sun’s magnetic field and sudden, faster-moving jets of material, which make the solar wind more turbulent. The plasma in the solar wind carries the magnetic field with it, stretching throughout the solar system in a giant bubble spanning more than 10 billion miles.

PSP found that reversals in the direction of the magnetic field, called switchbacks, can last from a few seconds to several minutes as they pass by the spacecraft. Clusters of these switchbacks were measured by PSP during its first two flybys.

“Waves have been seen in the solar wind from the start of the space age, and we assumed that closer to the Sun the waves would get stronger, but we were not expecting to see them organize into these coherent structured velocity spikes,” said Justin Kasper, principal investigator for SWEAP — short for Solar Wind Electrons Alphas and Protons — at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. “We are detecting remnants of structures from the Sun being hurled into space and violently changing the organization of the flows and magnetic field. This will dramatically change our theories for how the corona and solar wind are being heated.”

The switchbacks are thought to be “kinks” in the magnetic field rather than an actual change in the magnetic field. It is expected that the switchbacks will become more common as PSP gets even closer to the Sun during subsequent flybys.

PSP also observed the rotation of the solar wind, for the first time. When first released from the Sun, the solar wind rotates along with it, kind of like how the outer part of a carousel rotates. The farther out you are from the center of the carousel, or the Sun, the faster you move. At some distance between the Sun and Earth, the solar wind stops rotating and continues outward in a straight line. The rotation, observed at 20 million miles from the Sun, was stronger than had been predicted, and the transition to a straight outward flow also more sudden than had been anticipated.

“The large rotational flow of the solar wind seen during the first encounters has been a real surprise,” said Kasper. “While we hoped to eventually see rotational motion closer to the Sun, the high speeds we are seeing in these first encounters is nearly ten times larger than predicted by the standard models.”

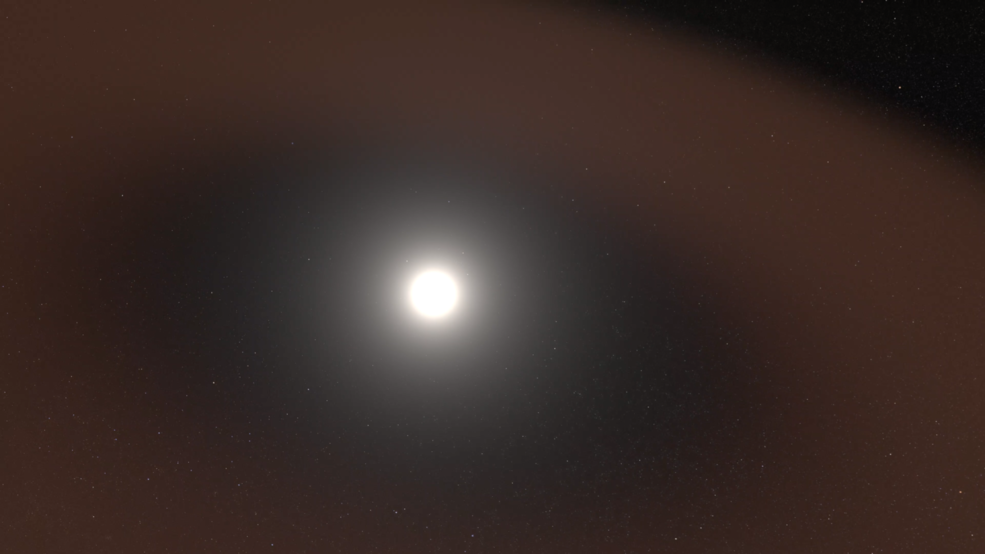

PSP also saw a thinning of cosmic dust near the Sun. This had been expected, since any dust close to the Sun would be heated and turned into a gas. This would have the effect of creating a dust-free zone near the Sun. PSP used its WISPR imager to show how the dust starts to thin out about 7 million miles from the Sun. That decrease continued until at least 4 million miles from the Sun, the limit of WISPR’s measurement capability.

“This dust-free zone was predicted decades ago, but has never been seen before,” said Russ Howard, principal investigator for the WISPR suite — short for Wide-field Imager for Solar Probe — at the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, D.C. “We are now seeing what’s happening to the dust near the Sun.”

Scientists think that the truly dust-free zone starts about 2-3 million miles from the Sun. PSP will reach that zone later in 2020 during its sixth flyby.

Finally, PSP is helping scientists learn more about space weather and how it affects Earth. Both electrons and ions get ejected from the Sun at almost the speed of light, and can be dangerous for both spacecraft and astronauts. PSP’s ISʘIS instruments, led by Princeton University, have measured several never-before-seen energetic particle events. These events are so small that all traces of them are gone before they reach Earth or any near-Earth satellites. But close to the Sun, they are still very energetic. PSP detected a rare type of particle burst with a particularly high number of heavier elements, which suggests that these types of events may be more common than previously thought.

“It’s amazing – even at solar minimum conditions, the Sun produces many more tiny energetic particle events than we ever thought,” said David McComas, principal investigator for the Integrated Science Investigation of the Sun suite, or ISʘIS, at Princeton University in New Jersey. “These measurements will help us unravel the sources, acceleration, and transport of solar energetic particles and ultimately better protect satellites and astronauts in the future.”

As noted in a press release from UC Berkely, “There was a major space weather event in 1859 that blew out telegraph networks on Earth and one in 1972 that set off naval mines in North Vietnam, just from the electrical currents generated by the solar storm,” said Stuart Bale, a University of California, Berkeley, professor of physics and lead author of an article about new results from the probe’s FIELDS experiment. “We’re much more of a technological society than we were in 1972, the communications networks and the power grid on Earth are extraordinarily complex, so big disturbances from the sun are potentially a very serious thing. If we could predict space weather, we could shut down or isolate parts of the power grid, or shut down satellite systems that might be vulnerable.”

The WISPR instrument was also able to view other structures in the corona and solar wind in unprecedented detail. This includes coronal mass ejections, which can produce auroras but also damage power grids and even pipelines.

“Since Parker Solar Probe was matching the Sun’s rotation, we could watch the outflow of material for days and see the evolution of structures,” said Howard. “Observations near Earth have made us think that fine structures in the corona segue into a smooth flow, and we’re finding out that’s not true. This will help us do better modeling of how events travel between the Sun and Earth.”

PSP’s next flyby of the Sun will occur on Jan. 29, 2020. This is one of 21 more flybys to come, each one a bit closer to the Sun than the previous one. At its closest, PSP will come to within 3.83 million miles of the Sun’s blazing surface.

“The Sun is the only star we can examine this closely,” said Nicola Fox, director of the Heliophysics Division at NASA Headquarters. “Getting data at the source is already revolutionizing our understanding of our own star and stars across the universe. Our little spacecraft is soldiering through brutal conditions to send home startling and exciting revelations.”

More information about Parker Solar Probe is available on the mission website. and data from the first two flybys is available here. The media teleconference, with additional graphics, can be viewed here.

.

.

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook and Twitter!

.

.

Missions » Parker Solar Probe »

So, could an e-sail make a turn during a switchback?