Last week, U.S. astronaut Christina Koch returned safely to Earth, wrapping up the longest single space mission ever accomplished by a woman; an astonishing 328 days, easily surpassing the previous record-holder, Peggy Whitson, and coming less than two weeks shy of exceeding the 340-day mission of Scott Kelly in 2015-2016. Women have been setting records off-Earth for almost six decades, ever since Soviet cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova became the first female spacefarer in June 1963. Since then, women have spacewalked, they have worked for hundreds of days aboard space stations and—25 years ago, this week—they entered the spacecraft’s “front seat” for the first time. In February 1995, Eileen Collins became the first woman to serve as a Space Shuttle pilot. In time, her career would also see her command two missions, including the first flight after the Columbia tragedy.

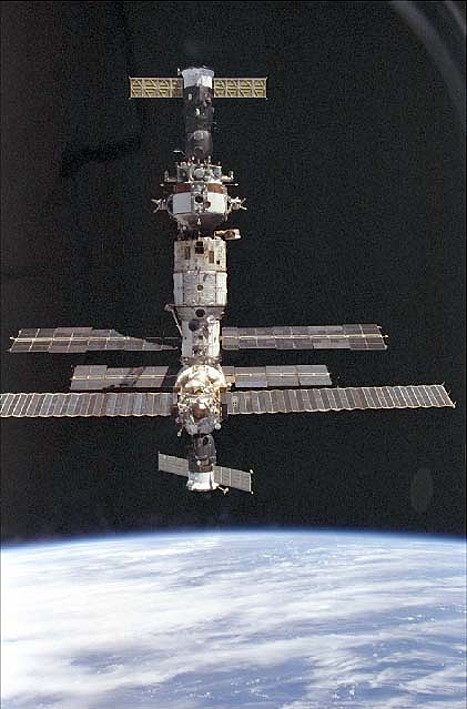

As detailed in last weekend’s AmericaSpace history article, STS-63 was a remarkable shuttle flight, not only because of Collins’ presence, but also the multi-faced smorgasbord of activities performed during its eight days in orbit. Joining Collins were Commander Jim Wetherbee and Mission Specialists Bernard Harris, British-born Mike Foale, Russian cosmonaut Vladimir Titov and Janice Voss. Twenty-three biomedical and technology experiments were performed inside the Spacehab-3 pressurized lab in shuttle Discovery’s payload bay, the free-flying SPARTAN-204 satellite was deployed and retrieved to conduct two days of intensive solar research, the first British and African-American spacewalkers strutted their stuff in the void…and, for the first time, the shuttle performed a rendezvous with another inhabited spacecraft in orbit: Russia’s Mir space station.

But STS-63 hit a serious obstacle almost as soon as the shuttle reached orbit, when two of the 44 Reaction Control System (RCS) thrusters—principally required for orbital maneuvering—began to exhibit irregularities. The two troubled thrusters were situated on Discovery’s aft end, one on her port side (L2D) and one on the starboard (R1U). The former was “deselected” and remained out of use for the rest of the mission, but R1U was classified as a primary thruster for the Mir rendezvous and its full functionality was paramount if the STS-63 crew were to be permitted to advance closer than about 1,100 feet (330 meters) from Mir. Matters worsened when a nose-mounted RCS thruster (F1F) also began leaking. Although the nose thruster issue was later resolved, that of R1U continued to linger.

When the crew bedded down for the night on 5 February 1995, the evening before the Mir rendezvous, Discovery trailed the Russian space station by 1,150 miles (1,850 km) and was closing on its quarry by about 80 miles (130 km) per orbit. Early next morning, STS-63 Commander Jim Wetherbee was awakened to encouraging news: the R1U leak had slowed and stabilized, but had not yet stopped. From the shuttle’s aft flight deck windows, Wetherbee could see that its conical plume was less pronounced and U.S. and Russian flight controllers reached agreement on two possible forward plans. The first called for Discovery to maneuver, as planned, to 33 feet (10 meters), whilst the second adopted a more conservative approach, reaching no nearer than 400 feet (120 meters).

Kicking off the final stage of the rendezvous, Wetherbee fired the RCS at 9:16 a.m. EST and again at 10:02 a.m. to decrease his rate of closure along the so-called “V-Bar,” approaching Mir from “behind,” along its velocity vector, or direction of travel, toward the station’s Kristall module. Later, at 11:37 a.m., at a distance of 9.2 miles (14.8 km), he would perform the Terminal Initiation (TI) burn, to bring the shuttle to a halt 400 feet (120 meters) “ahead” of Mir, about one orbit later at 1:16 p.m. At this stage, the shuttle’s rendezvous radar would begin to provide range and range-rate data, and Wetherbee would take manual control just after passing about a half-mile (0.8 km) below Mir.

In their seminal work Shuttle-Mir: The United States and Russia Share History’s Highest Stage, Clay Morgan noted that STS-63 Flight Director Bill Reeves struggled to explain the effect of the RCS problems to his Russian counterparts.

After one presentation, they asked him a rather odd question: “We understand what you’re saying, but what about the 180-gram snowball?”

Reeves stared blankly at them. “What are you talking about?” “The 180-gram snowball in your fax.”

It transpired that a team of NASA engineers had produced an extremely remote, worst-case plan for an RCS thruster freezing and becoming packed with ice. Communications links between Moscow and Houston were relatively poor and the fax was mistakenly sent directly to the Russians, bypassing Reeves, and thereby leaving in the unenviable position of having to explain that the RCS issue aboard STS-63 was by no means a critical problem.

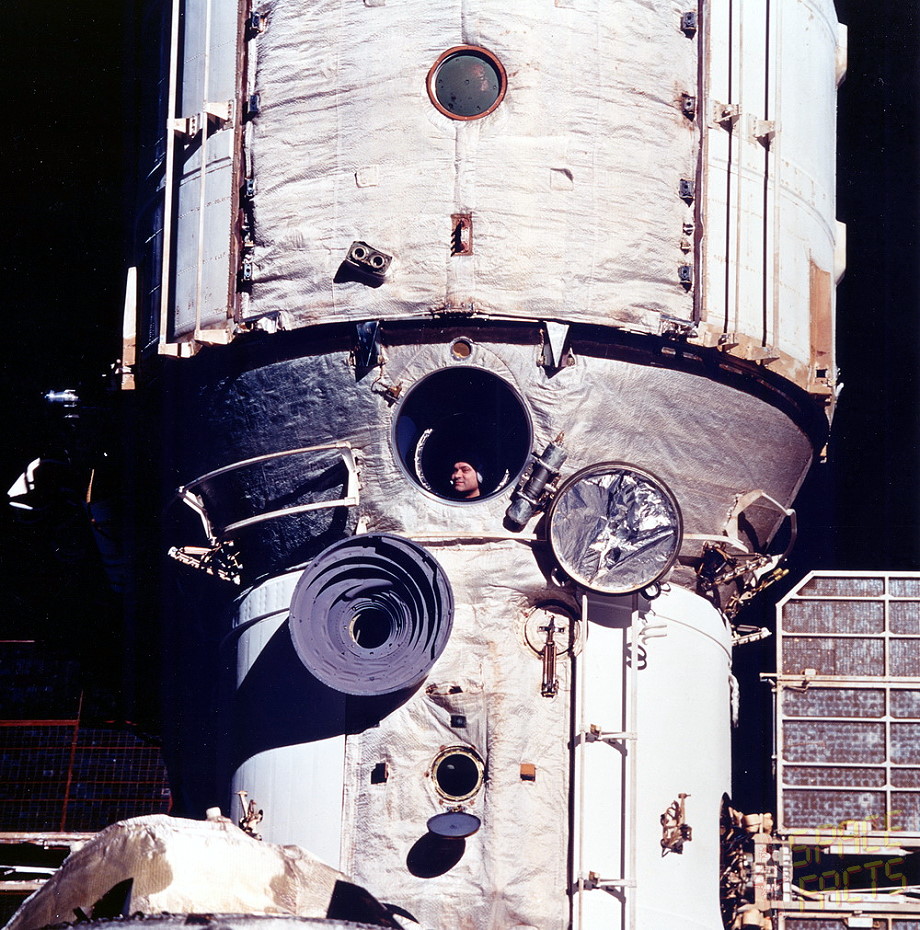

During the final rendezvous, the decision point was approaching about whether Discovery would perform a flyaround of Mir at 400 feet (120 meters) or continue to 33 feet (10 meters). That decision was relayed to the crew, not by Capcom Story Musgrave, but by Russian cosmonauts Aleksandr Viktorenko, Yelena Kondakova and Valeri Polyakov, aboard the space station itself. “We were testing out a new VHF radio that…all the crews used to talk directly with Mir,” Wetherbee later recalled. “You need to have an ability for the crew members to talk to each other, to co-ordinate things separately from the air-to-ground voice loop, from the ground control center in Moscow and from the orbiter to the control center in Houston. We had a separate communication, directly with Mir. The two mission control centers were co-ordinating the approach and they finally had agreed that they were going to let us make the final approach, but Houston didn’t tell us right away. We heard from Mir, from the Russian cosmonauts, that they were going to give us a Go.”

Unfortunately, the actions of the STS-63 crew were being recorded and broadcast live in Houston, although without audio, and there was some surprise when Mission Control saw the astronauts and Titov cheering and clapping. Viktorenko, Kondakova, and Polyakov had stolen their thunder, and Wetherbee had to tell his crew to calm down until they were given a definitive Go. Finally, Musgrave’s voice crackled across the airwaves: “We think you know this, because of the reaction we saw, but you do have a final Go to approach to 10 meters!” As if to echo Musgrave’s words, the STS-63 “simulated” their profound euphoria for the second time.

Flying the orbiter from instruments on the aft flight deck, Wetherbee intersected the V-Bar and after passing within 1,100 feet (330 meters) began executing RCS firings in a so-called “Low-Z” mode, whereby he employed thrusters which were slightly offset to the space station, rather than those which pointed directly at Mir. This helped to eliminate the possibility of contamination. Additional laser ranging data was provided by the Trajectory Control System (TCS), mounted in Discovery’s payload bay, and Wetherbee made use of the centerline camera in the roof window of Spacehab-3. At 400 feet (120 meters), he halted Discovery to await permission to advance closer. At 200 feet (60 meters), VHF ship-to-ship radio communications was initiated between the shuttle and Mir’s crews, and, by 2:23:20 pm, Discovery reached a distance of 37 feet (12 meters) from the station.

At least, that was the detail in the issued press releases. “The closest point of approach between structure was 33 feet,” said Wetherbee in his NASA oral history. “The number that was reported in the press was 37 feet, because that was the distance between the laser system and the target on Mir. You had to triangulate and that’s the longer hypotenuse of the triangle. Not that that matters; it was just interesting to see that when we came back it was reported, and is still reported, as 37 feet, but it really was 33 feet and not one centimeter closer. We did not get a single inch closer to Mir.” True to his word, Wetherbee had flown the first-ever rendezvous between a shuttle and a space station perfectly and with precision.

In the hours before the event, he had another issue on his mind: the right words to say over the space-to-ground communications loop when U.S. and Russian piloted spacecraft reached their closest point in orbit for almost 20 years. Wetherbee knew that the rendezvous would be watched by both a U.S. audience and a Russian audience and he was determined to deliver his message in both languages. That proved easier said than done, for although he had studied a little Russian, his powers of translation were poorer, and he approached Vladimir Titov for help. He wrote down what he wanted to say, showed none of his other crewmates, and passed it to Titov, who read it and translated it on his kneeboard. Armed with the translation, Wetherbee practiced a handful of times until he was satisfied that he could deliver the message and properly pronounce the words. As the point of closest approach neared, the time to speak those words finally came.

“As we are bringing our space ships closer together, we are bringing our nations closer together,” Wetherbee told Viktorenko, via the VHF radio link. “The next time we approach, we will shake your hand and together we will lead our world into the next millennium.”

“We are one. We are human,” came Viktorenko’s heartfelt reply.

For the three cosmonauts aboard Mir, there was no noticeable vibration or movement in the station’s solar arrays and its attitude-control system performed normally. Wetherbee held Discovery at 37 feet (12 meters) for about 15 minutes, before withdrawing to a distance of 400 feet (120 meters) by 3:00 p.m. He then completed a slow, quarter-loop flyaround of Mir and conducted a final separation manoeuvre at shortly after 4 p.m. This positioned the orbiter “ahead” of Mir and began their departure, opening up the distance between them with each successive orbit. Fortunately, no other RCS issues arose during the rendezvous. During a subsequent ship-to-ship communications session, relayed through an interpreter in Houston, Wetherbee and Viktorenko shared their personal perspectives of the historic operation. For Wetherbee, the high point was when Mir maneuvered into a new attitude as Discovery performed the quarter-loop flyaround around the station. “It was like dancing in the cosmos,” he told Viktorenko. “It was great.” The two commanders pledged to meet on Earth after their respective missions were over.

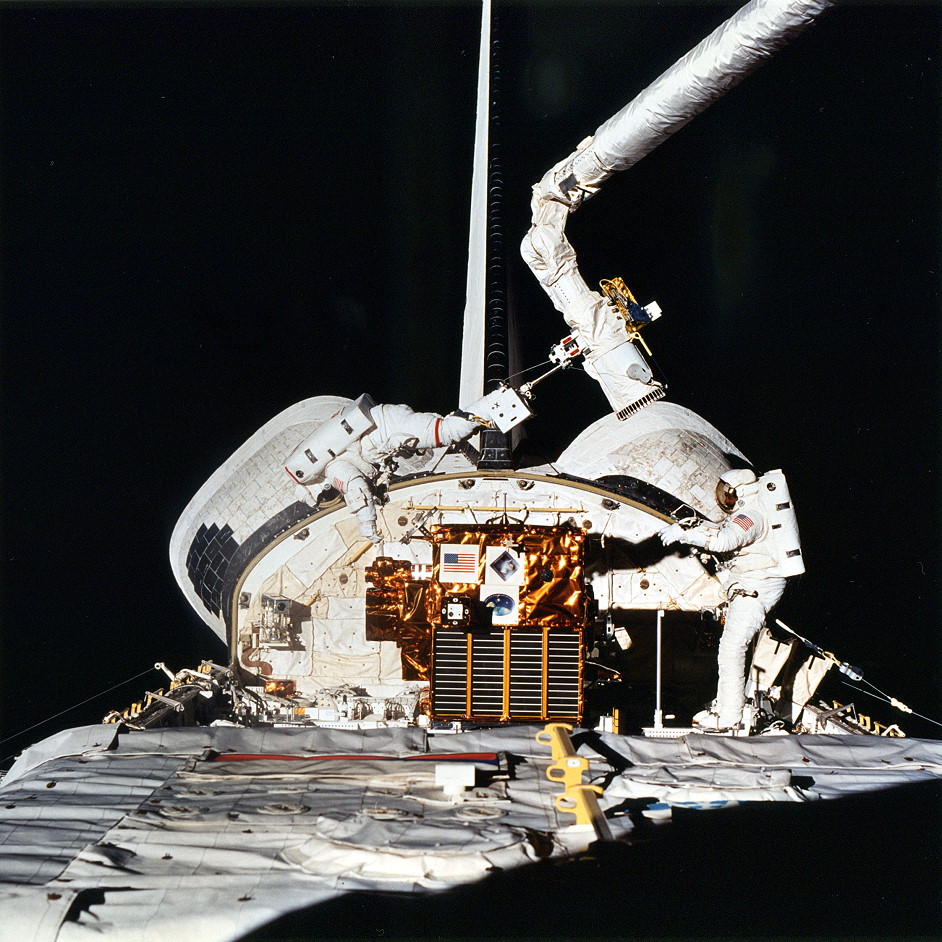

With the Near-Mir operations behind them, the STS-63 crew turned their attention to the deployment of the SPARTAN-204 astronomy satellite on 7 February. It spent two days in free flight, utilizing the Naval Research Laboratory’s Far Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrograph (FUVIS) for astronomical observations, before being retrieved and returned to its berth in the payload bay. It was also used during a five-hour EVA by STS-63 Mission Specialists Bernard Harris and Mike Foale—who became, respectively, the first African-American and first British-born spacewalkers—on the 9th, during which they evaluated new garments and tools to handle the deep cold of working in orbital darkness. After a troubled, but ultimately triumphant eight days in space, Discovery returned to Earth on 11 February, having played an enormous and critical part in making the shuttle-Mir and International Space Station (ISS) programs possible.

.

.

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook and Twitter!

.

.