The United States has lost a pioneer of its early human space program with Wednesday’s passing of Skylab astronaut Jerry Carr, at the age of 88. The retired Marine Corps colonel served for more than a decade in NASA’s astronaut corps and commanded the final manned voyage to the Skylab space station, which established a new world endurance record of 84 days off the planet between 16 November 1973 and 8 February 1974. Not for almost four years after the return to Earth of Carr and his Skylab 4 crewmates Ed Gibson and Bill Pogue was their record finally eclipsed by the Soviet Union. “NASA and the nation have lost a pioneer of long-duration spaceflight,” said NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine. “We send our condolences to the family and loved ones of astronaut Gerald “Jerry” Carr, whose work provided a deeper understanding of life on Earth and in space.”

Gerald Paul Carr came from Denver, Colo., where he was born on 22 August 1932. He grew up in Santa Ana, Calif., where he received much of his education. In his teens, the boy and a friend cycled from their homes to Orange County Airport—now John Wayne Airport—to wash the aircraft in exchange for a 20-minute flight in an old Martin Aviation Taylorcraft. For Carr, the flying bug bit him early.

An active Boy Scout, he became an Eagle Scout and junior assistant scoutmaster, participating in student government and playing high school football. He became a Navy reservist in 1949, during his final year of high school, and recalled in a NASA oral history that his duties included cleaning the F-6F Hellcat, checking its oil and fuel, starting its engine and warming it up each morning.

He entered the University of Southern California to study mechanical engineering, as part of the Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC) detachment. Decades later, Carr remembered one of his commanding officers giving him two choices: if he wanted to join the Navy, he could go to the Naval Academy in Annapolis, Md., or if he wanted to join the Marine Corps, he could select a university of his own choice.

The benefits of taking the second option, the commanding officer told him, were twofold. Firstly, the Marines cared not a jot where he came from or if he was an Academy graduate. And secondly, there seemed little point in locking himself up in the Bastille-like regimen of the Naval Academy for four years, when Carr could go to a normal college with girls for four years. After some thought, Carr picked the Marines.

He received his degree in 1954 and entered basic school in Virginia, undertook flight instruction in Florida and Texas and was assigned to the All-Weather Fighter Squadron, VMF-114, also known notoriously as the “Death Dealers”.

This squadron had earned renown for providing close aerial support during the bloody Battle of Peleliu in Japan in 1944. For three years, Carr flew the Grumman F-9F Cougas and Douglas F-4A Skyray and deployed to the Mediterranean Sea aboard the USS Franklin D. Roosevelt as part of efforts to qualify himself to operate from aircraft carriers.

Midway through this deployment, Carr was told of his selection for the Naval Postgraduate School. He graduated in aeronautical engineering in 1961 and was sent to Princeton University to complete his master’s degree.

As part of his thesis, the young Marine focused upon aircraft stability and control and in 1962 he was sent to Marine Corps Air Station Beaufort in South Carolina, where he flew the F-8 Crusader and was maintenance officer of VMF-122. Carr then deployed to Japan, where he was present in August 1964 when the Tonkin Bay crisis dramatically escalated the Vietnam War.

Upon his return to the United States, Carr worked on fighter aircraft trajectory designs to intercept different aerial targets and it was at this point that he learned of NASA’s plan to select a new class of astronaut candidates.

He knew that two other Marines—Clifton “C.C.” Williams and America’s first man in orbit, John Glenn—had been chosen for astronaut training and decided to give it a try. Late in 1965, as a “conditional candidate”, Carr completed NASA’s physical and psychological evaluations, but was convinced that his flat-footedness and susceptibility to hayfever would scupper his chances.

They did not. In April 1966, he received a call from Chief Astronaut Al Shepard, notifying him of his selection into the fifth group of NASA astronauts, a class which included nine future lunar voyagers and three future Moonwalkers. And it is quite possible that Carr might (had circumstances been different) have walked on the lunar surface himself.

During stints on the support crews for Apollo 8 in December 1968 and Apollo 12 in November 1969, he helped to develop and maintain the astronauts’ flight data files. His performance so impressed Apollo 12 Commander Charles “Pete” Conrad that he was instrumental in recommending Carr to command the final Skylab crew.

But Carr’s experience with the Apollo Lunar Module (LM) raised a reasonable possibility that he would draw at least a backup slot on one of the later Moon missions. Had the final three landings not been canceled due to budget cuts in the summer of 1970, it is quite possible that Carr might have been assigned as Lunar Module Pilot (LMP) for Apollo 19, alongside Commander Fred Haise and Command Module Pilot (CMP) Bill Pogue.

Sadly, it was not to be, and in late 1970 Chief Astronaut Tom Stafford called Carr to his office and asked him if he would be willing to fly with Pogue and another astronaut, physicist Ed Gibson, to Skylab. Their names were formally announced in January 1972.

The trio launched aboard their Apollo Command and Service Module (CSM) from Pad 39B at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida, atop a Saturn IB booster, on 16 November 1973.

Their launch had originally been scheduled for the 10th, which happened to be the official birthday of the Marine Corps, and missing this auspicious date upset Carr, who became the first Marine to command a crew of astronauts. In fact, to commemorate both the anniversary and the milestone, Gen. Robert Cushman, commandant of the corps, and several of his senior staff, intended to be on hand at the Cape to watch the launch.

Uniquely, they were the only all-rookie Apollo crew and only the the fourth crew of astronauts—after Gemini IV, Gemini VII and Gemini VIII—to include no experienced astronaut among its ranks. And when the CSM’s hatch was closed, the three of them looked at one another…and started giggling, “like a bunch of schoolgirls,” Carr reflected.

After almost a decade waiting for this moment, their excitement was understandable. Ascent, in Carr’s words, was like running down a railroad track on square wheels. It was the start of an 84-day mission which brought multiple twists and turns of fortune.

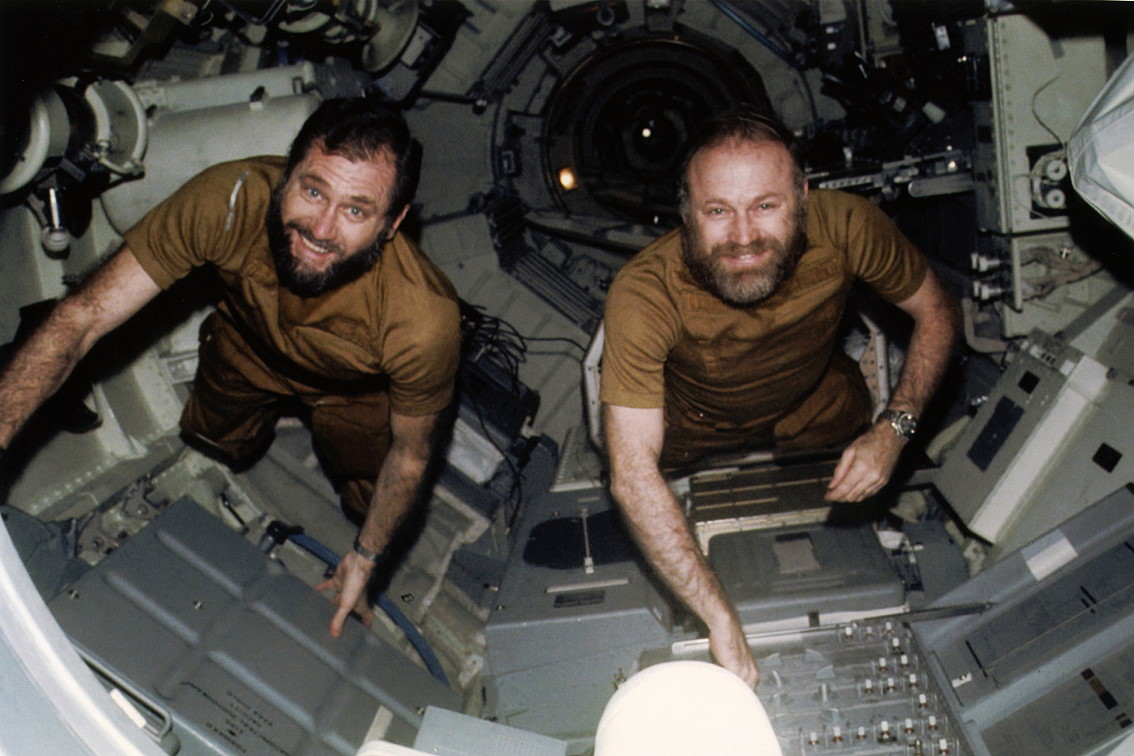

As previously described by AmericaSpace, Carr, Gibson and Pogue’s 84 days in space included the infamous concealment of a sick bag, a notoriously overworked crew and persistent (though unfounded) allegations of a “space mutiny”.

But it also included a vast amount of scientific research with the Earth Resources Experiment Package (EREP) and Apollo Telescope Mount (ATM), observations of Comet Kohoutek and Carr tested the Astronaut Maneuvering Unit (AMU), forerunner of the Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU). four sessions of Extravehicular Activity (EVA), totaling more than 22 hours. Of this figure, Carr himself logged three spacewalks with a career total of 15 hours and 49 minutes, including the first (and so far only) EVA to be performed on Christmas Day.

Returning to Earth on 8 February 1974, Carr, Gibson and Pogue logged 84 days, one hour and 15 minutes on their space mission to Skylab and circled the globe 1,214 times. Years later, Carr would state that “the medical stuff”—the huge corpus of data his crew brought back, which amply demonstrated that humans could indeed live for long durations off-planet—was perhaps the greatest contribution of his mission.

Carr retired from the Marine Corps, with the rank of colonel, and departed NASA in June 1977 to begin a second career as a professional engineer. Together with his wife, Patricia Musick, he founded CAMUS, Inc., in 1984, dedicated to developing crew systems for what later evolved into the International Space Station (ISS).

His family—to whom AmericaSpace extends its sincere condolences—also offered a touching tribute to a man who contributed enormously to enabling long-duration missions which today seem commonplace. “Throughout his life and career, Jerry Carr was the epitome of an officer and a gentleman,” they wrote.

“He loved his family, he loved his country and he loved to fly. We are all enormously proud of his legacy as a true space pioneer and of the lasting impact of his historic mission aboard America’s first space station. We will remember him most as a devoted husband, father, brother, grandfather, great-grandfather and uncle. We will miss him greatly.”

A true American hero.

R.I.P., Jerry.