Forty-five years ago, in May 1973, America launched its first space station—Skylab—into orbit. Its mission appeared jinxed from the outset, with aerodynamic forces during ascent ripping away a protective micrometeoroid shield and one power-producing solar array and leaving the second array clogged with debris. Eleven days later, after an enormous amount of replanning on the ground, Skylab’s first crew triumphantly brought the station back to life. Their record-breaking 28-day mission was followed by another record-breaking 59-day mission, leaving only the third crew of Commander Gerry Carr, Science Pilot Ed Gibson and Pilot Bill Pogue to stage a marathon 84-day expedition, beginning on 16 November 1973. As NASA and its international partners celebrate 20 years of the International Space Station (ISS) era this month, we are also reminded of the spectacular success of the final voyage to Skylab; a mission forever remembered—somewhat unfairly—in the public mind for two things: the concealment of a sick bag and the first “mutiny” in space.

On the eve of their launch, Carr, Gibson and Pogue were aiming for at least 60 days and perhaps as long as 84 days in orbit, making theirs the longest piloted space mission in history at that time. One of the main fears was that the crew might fall foul to “space sickness”, but with U.S. Air Force Thunderbird veteran Pogue aboard, the chances of him being affected seemed infinitesimally small. If anyone’s stomach could be turned inside-out by multiple aileron rolls and other intestine-churning maneuvers, with precious few ill-effects, then surely Pogue was the man.

Following the experiences of their predecessors, Carr, Gibson and Pogue beefed-up their exercise efforts to better combat the effects of prolonged exposure to microgravity. Another problem was that previous Skylab crews had hustled about their work with vigor and that course of action did not seem appropriate for three months in orbit. “We began telling some of the managers that we didn’t think that rate of work was wise for an 84-day mission, because we weren’t sure that we were going to be able to sustain it,” Carr told the NASA oral historian. “We thought that the workload should be slacked off some and there should be more rest. Everyone agreed to that and the experiments were slowed and spread out quite a bit.” Unfortunately, more experiments were added and Carr’s crew quickly found themselves over-committed. In orbit, it would lead to difficulties.

Launch was targeted for 10 November 1973, with the first of up to five spacewalks planned just a week later to install film into the station’s Apollo Telescope Mount (ATM). Repairs of an antenna, observations of Comet Kohoutek, retrieval of material samples from Skylab’s hull and the final collection of ATM film were scheduled for four successive Extravehicular Activities (EVAs) through mid-January 1974, with the astronauts due to return to Earth later that month or in early February. The precise duration of the mission, up to a maximum of 84 days, would be decided and implemented on a weekly basis at it moved into its final stages.

The Apollo Command and Service Module (CSM) and Saturn IB booster were readied for launch, but on 6 November a management meeting at Cape Kennedy, Fla., was interrupted by news that inspectors carrying out routine structural integrity tests had found hairline cracks in the aft attachments of eight stabilizing fins on the base of the first stage. More than a dozen cracks were detected. In all likelihood, they were age-related—this was the second-to-last Saturn IB to fly and the first stage had been delivered to the Cape more than seven years earlier and kept in storage—and exposure to the salty Florida air between August-November 1973 had not helped. With an alarming possibility that the compromised fins might be torn away during ascent, NASA postponed the launch for replacements to be installed. The work was completed on 13 November and launch rescheduled for the 16th.

Carr, a U.S. Marine Corps officer, was particularly upset, because 10 November was the official birthday of his parent service, and—with the exception of John Glenn, who flew alone on Friendship 7 in February 1962—he would become the first Marine to command a space mission. In order to commemorate both the anniversary and Carr’s milestone, the Commandant of the Marine Corps, Gen. Robert Cushman, and several of his senior staff, would visit the Cape to witness the launch. The bitter disappointment quickly turned to frustration, then humor, as the Saturn IB quickly earned the moniker of “Ol’ Humpty Dumpty”. The nickname did not sit well with some members of the repair team, but on launch morning Carr, Gibson and Pogue were inserted into the command module…and greeted with a strange message from them. “Good luck and Godspeed,” it read, “from all the King’s Horses and all the King’s Men.”

As propellant flooded into the combustion chambers of the eight H-1 engines of the rocket’s first stage, Pogue momentarily wondered if someone had simultaneously flushed every toilet in the Astrodome. Seconds later, at 10 a.m. EST on 16 November 1973, the rocket roared away from Pad 39B, and the men’s pulses skyrocketed with it; Pogue’s accelerated from 50 to 120 at the instant of liftoff. Ascent vibrations were so severe that the crew struggled to read their instruments and the incessant din made it difficult to hear each other’s voices through the intercom between their suits. Carr compared the experience to being an insect, glued to a paint-shaker, or riding a train with square wheels. After the first stage was jettisoned, however, and the second stage took over, the G-forces dropped from 4G to 1.5G and the remainder of the journey to orbit was much more smooth.

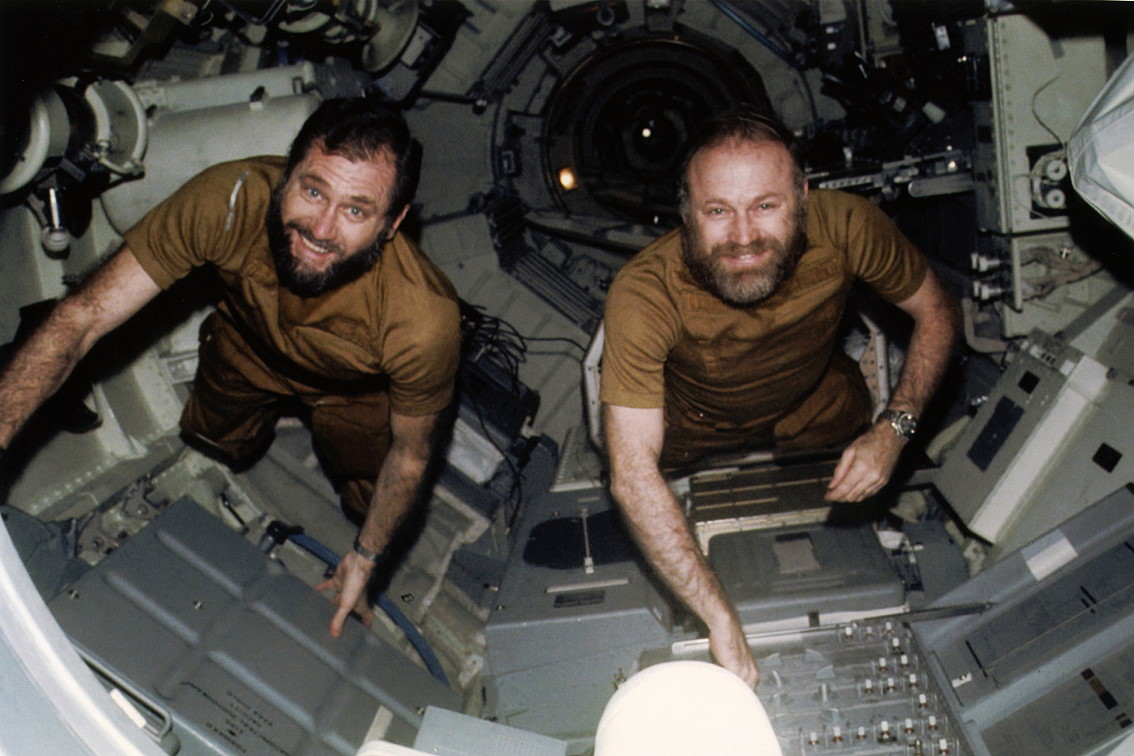

Eight hours later, the crew docked to Skylab and it was intended for them to remain aboard the command module until the following morning, to aid their adaptation before entering the large, disorientating open volume of the station itself. They worked late into the night, stowing equipment, and at some stage sickness gripped Bill Pogue. It initially took the form of a headache and nausea and attempts to eat some food—a mouthful of stewed tomatoes, the only item left on his evening-meal ration—quickly (and unsurprisingly) sent him scurrying for his sick-bag.

Thus, in one of the great ironies of this mission, the Thunderbird suffered space sickness and yet his crewmates did not. It was another indication that the medical community’s understanding of the ailment was still improperly understood and, even today, its causes and predictors of which astronauts it might affect remain unclear. However, at that particular moment, the crew’s main concern was what to tell Mission Control. Skylab had drifted out of radio communications and Gibson suggested disposing of the sick bag in the trash airlock and keeping quiet about the matter. Carr agreed that it would prevent the medical community getting “all fuzzed” and hopefully enable them to get their busy slate of mission tasks underway. They tried putting Pogue into Skylab’s docking tunnel, in the hope that air from a cabin fan might make him feel better, and Carr told Mission Control that his crewmate had experienced nausea and had not eaten all of one of his meals.

Unfortunately, one of Pogue’s responsibilities was the communications system and—as specified in his checklist—he had left a switch to record their in-cabin conversations in the “on” position. Whilst the astronauts slept, Mission Control downloaded the tape and heard their entire conversation about disposing of the evidence.

Next morning, the 17th, Pogue felt a little better, but took things slowly as he and his crewmates attempted a light breakfast. Later that day, Chief Astronaut Al Shepard came onto the communications loop and addressed Carr directly.

“I just wanted to tell you,” he said, “that on the matter of your status reports, we think you made a fairly serious error in judgement here in the report of your condition.”

Carr accepted the rebuke. “Okay, Al, I admit it was a dumb decision.”

But Shepard would not be put off. If Pogue’s sick bag had been disposed in the trash airlock, it could have compromised many of the mission’s medical experiments, including mineral-balance investigations. The incident seemed comparatively minor in some minds, although it underscored a growing concern that Carr’s crew were unwilling to engage in frank and open conversations with Mission Control. Flight Director Neil Hutchinson did not doubt the astronauts’ integrity, but made certain that any further problems would require mission controllers to take immediate steps to set things right. And over the coming days, as the astronauts fell behind schedule, thanks to an overloaded program of work, the situation would go from bad to worse.

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook and Twitter!

.