Forty years ago, nine men occupied America’s first space station, high above the Earth. Much of the history of Skylab is clouded by its early troubles following launch—one of its solar arrays was torn off, another left jammed by debris—and the actions of its heroic astronaut crews to bring it back from the brink of outright failure and transform it into a remarkable success cannot be underestimated. Yet Skylab was always intended as a quantum leap in the U.S. human spaceflight arena, with dozens of scientific experiments planned. One of the most visible, at least in the winter of 1973-74, was the arrival of a long-haired messenger, a few tens of millions of miles from Earth: Comet Kohoutek.

Comets have long been thought to carry ill-tidings and, certainly, for the first year of Skylab’s life, good and bad luck were but different faces of the same coin. Nearly a thousand years ago, a comet convinced King Harold’s men that cruel fortune awaited them on the battlefield of Hastings, and to the ancients they foretold imminent catastrophe: a plague or a flood, perhaps, or the impending death of a nobleman or king. To the biblical Book of Revelation and the Jewish Book of Enoch, such “falling stars” were believed to represent heavenly visitations, and in 7 BC King Herod is said to have been warned that the apparition of a “hairy star” over Judea would herald the birth of a boy whose achievements would outshine his own.

Indeed, until the 16th century, the mainstay of scientific opinion about the nature of comets rested with the Greek philosopher Aristotle, who believed that they could not possibly belong to the “perfect” celestial realm and posited that they were a phenomenon of the upper atmosphere, from which hot, dry exhalations gathered and burst into flame. Then, in 1577, the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe used measurements of a comet taken from several geographical locations, including some by himself, to determine that it must have been at least four times more distant from Earth than the Moon. In Brahe’s mind, comets could not be elements of the upper atmosphere, but must represent something from beyond.

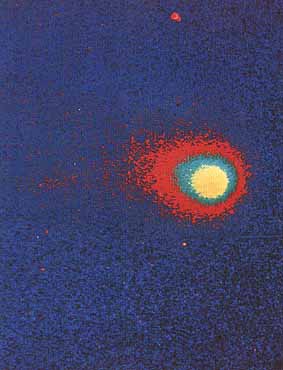

Since the beginning of the Space Age, our understanding of these long-haired messengers has sharpened: we now know them to possess irregularly-shaped nuclei of rock and water-ice and a multitude of other volatiles—prompting the nickname of “dirty snowballs”—and as they approach the inner Solar System, these volatiles quickly vaporise and stream away, carrying dust particles with them. These streams create a vast “atmosphere” around the comet (its “coma”), and the force exerted by the Sun’s radiation pressure and solar wind cause immense “tails” to form, sometimes many millions of miles long.

Our knowledge of their appearance, their composition, and their evolution has multiplied, thanks to our extraterrestrial emissaries: from Giotto’s impressive photographs of the nucleus of Halley’s Comet, with its “jets” of dust, in the winter of 1985-86, to Deep Space 1’s astonishing shots of the hot, dry Comet Borrelly 1 in September 2001, to Stardust’s collection of crystalline, “fire-born” material from Comet Wild 2 in January 2004, to Deep Impact’s spectacular effort to blast a man-made crater into Comet Tempel 1 in the summer of 2005. Further flights of exploration are also planned. A second voyage of Stardust revisited Tempel 1 in February 2011 to analyse the after-effects of that collision and to test the hypothesis that much of the ice in a comet is stored in subsurface “reservoirs.” Europe’s Rosetta spacecraft will land its instrumented Philae probe onto Comet Churyumov-Gerasimenko in November 2014. Once there, Philae will use harpoons and drills to physically anchor itself, for the first time, onto the surface of a comet.

As for Comet Kohoutek, it was first spotted on 7 March 1973, by Czech astronomer Luboš Kohoutek, a professor at the Hamburg-Bergedorf Observatory in West Germany, whilst he was undertaking observations of minor planets. At the time, it was little more than a diffuse point of light, moving slowly north-westward in the constellation of Hydra, but its distance from the Sun—some 5 Astronomical Units (AU) or around 460 million miles—quickly whetted astronomers’ appetites that it would be a particularly bright comet. Calculations by Brian Marsden of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Mass., added that it would reach a perihelion of just 0.14 AU and would subsequently pass Earth in January 1974 at a distance of just 60 million miles.

All in all, the early discovery of Kohoutek’s object pointed to something intrinsically brighter than Halley’s Comet and probably something quite large, too. Elizabeth Roemer of the University of Arizona estimated that the nucleus could measure 20 miles or more in diameter, whilst other astronomers speculated that it might weigh many billions of pounds. Spectroscopic evidence for water-ice had been obtained and astronomers had reason to hope that hydrogen cyanide and methyl cyanide—both “polyatomic molecules,” previously only detected in intergalactic space, never in comets—were present in the nucleus. Consequently, in the late spring of 1973, Comet Kohoutek carried much promise. Its hyperbolic trajectory led to theories that it originated in the Oort Cloud, a spherical “shell,” far beyond the orbit of Neptune on the very edge of the Solar System, and as such it was suspected that this might be the latest in a series of very infrequent visits to the inner Solar System. Unlike the “worn-out” Halley’s Comet, the possibility that Kohoutek might be a “virgin” comet from the Oort Cloud sparked optimism that it would offer scientists a chance to study material unchanged from the primordial state and that it might be visually stunning.

A spectacular display of “outgassing” of this material and a brilliant, glittering tail as it neared the Sun was also increasingly likely. Sky and Telescope magazine predicted in May 1973 that it should be a conspicuous, naked-eye object of first magnitude or brighter, whilst other writers expected it to rival or even surpass the best views of Halley’s Comet. It was predicted that by early 1974, after perihelion, Kohoutek’s tail would be a fully grown and shimmering “streamer,” extending across maybe one-sixth of the night sky. In such an eventuality, exulted Harvard astronomer and comet specialist Fred Whipple, it might “well be the comet of the century.”

Not everyone was convinced, however. Many observers acknowledged that comets were notoriously unpredictable, and even The New York Times warned that Kohoutek might not live up to its billing, but none of this deterred the sky-watchers of 1973. Kohoutek shows were held in planetariums around the world, binocular and telescope purchases picked up and escalated at an exceptionally brisk pace—one company even announcing a 200 percent profit in its sales—and the luxury liner QE2 sailed from New York with 1,700 passengers on a special “comet cruise.” New York’s Hayden Planetarium planned a spectacular, six-day “Flight of the Comet” aboard a chartered Boeing 747, in time for the January 1974 perihelion, when Kohoutek was expected to reach maximum visibility. With candlelit (and comet-lit, it would seem) dinners offered for a total package of more than a thousand dollars per person, it was bound to be spectacular.

Yet as one journalist later remarked, the desire for success has a tendency to make us smug, and although Kohoutek would indeed be visible to the naked eye and would reach a magnitude of about -3, it did not live up to the hype. Today, it is generally thought not to be a pristine Oort Cloud comet, but a rocky object from the Kuiper Belt, a disk of material in the outer reaches of the Solar System, a “long-period” comet which will not again grace humanity with its presence for another 75,000 years. In fact, perhaps a little unfairly, Kohoutek’s name has become synonymous with spectacular duds. As for the unfortunate ocean voyagers, their thousand-dollar QE2 dinner tables actually brought them little more than disappointment, cloudy skies. and seasickness. …

Today, Kohoutek’s greatest claim to fame is that it appeared when it did: for America’s Skylab space station, with its powerful Apollo Telescope Mount (ATM), was in orbit and its second and third human crews were primed and ready for their missions of discovery. The timing could hardly have been better. Astronaut Karl Henize, himself an astronomer, summed up an excited spirit of optimism in the scientific community as spring burned into summer and summer cooled into fall in 1973. He saw Kohoutek, potentially, as an astronomical “Rosetta Stone”: an unexpected find, an incredibly fortuitous quirk of serendipity which might reveal vital clues to unlock the mystery of how the Sun and its attendant planets—and, by extension, ourselves—came into being more than 4.5 billion years ago.

By the fall of 1973, the third and final crew of Skylab—astronauts Gerry Carr, Ed Gibson, and Bill Pogue—were primed and ready to launch in November and spend as long as three months aboard the space station. The first few weeks of their mission were difficult, due to excessive overwork, but they clearly savored the appearance of Kohoutek: in addition to building a makeshift Christmas tree from food containers and packing material, they crafted a long-tailed star from silver foil and put it in pride of place at the top. In late November, Pogue began taking images of Kohoutek’s intrinsic brightness and commenced analyses of its coma and tail over the following days.

On Christmas Day, Pogue and Carr spent seven hours outside on a spacewalk, during which time they were assigned the task of photographing the comet. They set up a camera, mounting it onto a strut and positioning it in such a way that Skylab’s ATM solar arrays blocked the Sun. Although neither man could physically “see” Kohoutek, they followed instructions from Mission Control. “The instructions were clear and it was a fairly easy job,” recalled Pogue in his NASA oral history. “I turned on the camera and I was finished.” Another EVA on 29 December, this time by Carr and Gibson, conducted more observations using a far ultraviolet camera provided by the Naval Research Laboratory.

Like many disappointed observers back on Earth, the astronauts could hardly describe the comet as brilliantly spectacular, but Carr was impressed, nonetheless. “It was so faint,” he told the NASA oral historian, “that we really had to work to find it. Once we did find it, we observed a gorgeous thing: small, faint, but gorgeous.” Still, although he and Gibson shot as much film as they could during their three and a half hours outside, they privately doubted that it was sensitive enough to record sufficiently good data. Over the next few days, from inside the workshop, the best results came from the ATM’s coronagraph … and, interestingly, from a series of pencil sketches by Gibson himself, today enshrined in the Smithsonian.

With the dawn of the New Year, 1974, much of the comet-hunting on the ground had come to an end, and there was disappointment that Kohoutek had not lived up to its media-hyped billing. Journalists started calling it the “Flop of the Century,” ignoring the scientific yield and focusing only on its brightness as a marker of significance. In reality, the fault lay fairly and squarely upon their shoulders; for it was the media which falsely treated Kohoutek as a sure thing. In March 1974, Sky & Telescope glumly told its readers that, whilst professional astronomers were jubilant with their observations, “the general public wondered what had happened to the spectacle promised by the news media.”

This is part of a series of history articles, which will appear each weekend, barring any major news stories. Next weekend’s article will focus on Gemini V, a crucial mission in August 1965 which demonstrated that astronauts could survive in space for eight days: the minimum duration necessary to travel to the Moon and back.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter:@AmericaSpace