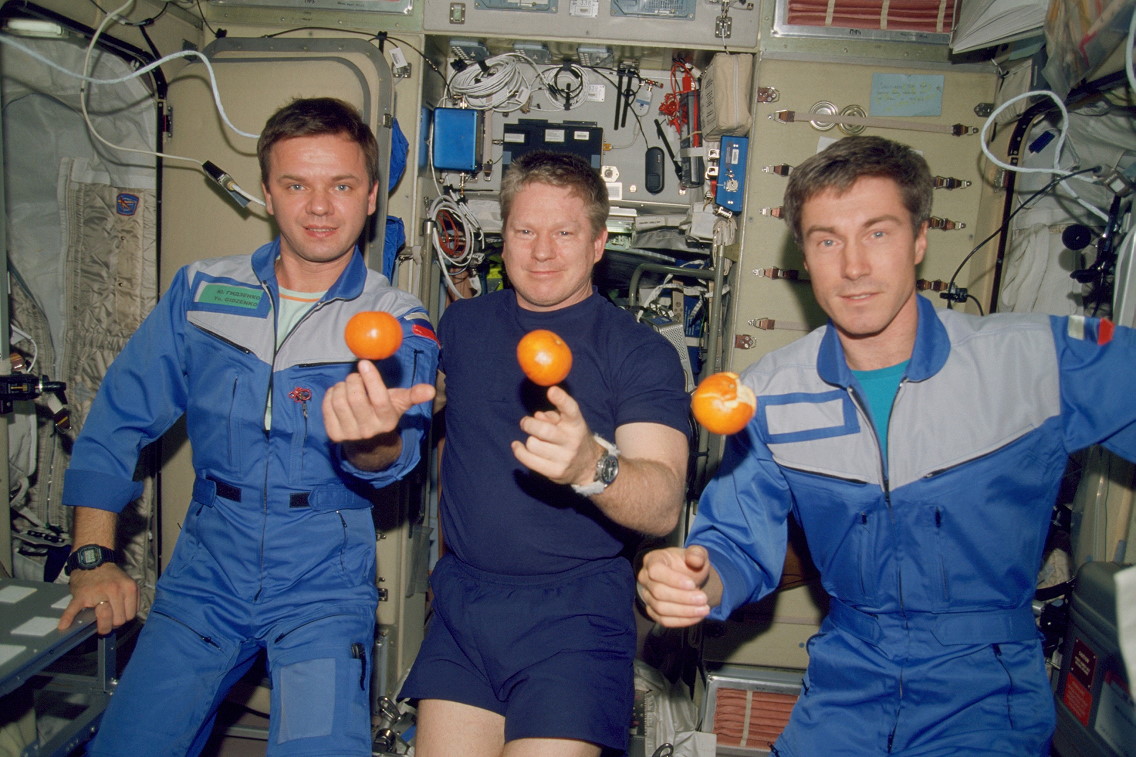

At 4:21 a.m. EDT on Monday, 2 November, the International Space Station (ISS)—which has to date provided an off-Earth homestead for 241 humans from 19 sovereign nations—will pass its 20th year of continuous habitation, extending right back to the historic arrival of Expedition 1 Commander Bill Shepherd and his Russian crewmates Yuri Gidzenko and Sergei Krikalev aboard Soyuz TM-31.

Launched on 31 October 2000, the three men had been training together for over four years and would go on to spend 4.5 months overseeing perhaps the most critical phase of ISS activation. During their 136 days aboard the infant space station, Shepherd, Gidzenko and Krikalev welcomed three Space Shuttle crews as their planet-circling habitat gradually grew into the largest and most massive inhabited structure ever placed outside of Earth’s atmosphere.

For Shepherd, his personal and professional relationship with the creation that would become the ISS had extended to a time far earlier than commanding its first long-duration increment. In June 1993, with three shuttle missions already under his belt, Shepherd was named by NASA Administrator Dan Goldin as an Assistant Deputy Administrator (Technical), based at the agency’s Washington, D.C., headquarters, with responsibility for leading the transition effort as Space Station Freedom was rescoped and redesigned to become the embryo of what became the ISS.

Only a few months later, Shepherd was named as the Space Station Program Manager at the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas, a position which he held for the next two years.

Remaining available to return to active astronaut training, it seemed likely that Shepherd would draw an early ISS assignment and in January 1996 he and Krikalev were named to Expedition 1, with launch initially targeted aboard a Russian Soyuz spacecraft in the summer of 1998. Krikalev had trained extensively with NASA, becoming the first Russian to fly aboard the shuttle and seemed an obvious choice.

Interestingly, the third member of Expedition 1 went unannounced for some time, which Bryan Burrough, in his controversial book, Dragonfly, attributed in part to the thorny question of whether a Russian or an American should command Expedition 1. Burrough suggested that veteran cosmonaut Anatoli Solovyov—who had commanded three previous long-duration missions to Russia’s Mir space station—had been assigned to Expedition 1, but had resigned his position when it became clear that Shepherd would command.

“His resignation,” wrote Burrough, “capped months of behind-the-scenes maneuvering.” Whatever the reality of the situation, Yuri Gidzenko was assigned to Expedition 1 and by May 1997 was deep into training with Shepherd and Krikalev, tracking a launch in early 1999.

Unfortunately, delays in the arrival of Russia’s Zvezda service module—which provided critical crew quarters and life-support functionality for the early expeditions—pushed its launch back from the fall of 1998 to April 1999 and beyond, before it eventually reached orbit in July 2000. This created a domino-like impact on a stream of shuttle assembly missions and the Expedition 1 crew found their own launch pushed back to 31 October 2000, exactly 20 years ago today.

“The day went by really fast,” Shepherd remembered in a 2010 NASA interview to commemorate the 10th anniversary of continuous occupation of the ISS. “It was foggy, a kind of dew on all the windows. I waved goodbye to my wife, got on the bus, went down to the Launch Assembly Area and we got our space suits on. Then, out of nowhere, my wife came up when we were suited up and gave me a big hug, which was something you just don’t do in our program.”

Upon arrival at Baikonur’s Site 1/5—the famed “Gagarin’s Start”, from which Yuri Gagarin had begun his epochal voyage into orbit—they beheld the enormous Soyuz-U booster, topped by their Soyuz TM-31 spacecraft, and 400 well-wishers. To Shepherd, it could not have contrasted more markedly from his shuttle career. “This is a couple of million pounds of rocket, all ready to go fly in space, all sitting there steaming and smoking, and we got 400 people, right there,” he said, incredulously.

With Gidzenko in Soyuz TM-31’s center seat, commanding the flight uphill, Krikalev in the left-side “Flight Engineer-1” position and Shepherd in the right-side “Flight Engineer-2” position, the first long-duration crew of the ISS began their voyage at 12:53 p.m. local time (2:53 a.m. EST). “The main thought I had was now it’s starting,” Krikalev recalled in a NASA interview. “This is our first work and, oftentimes, it’s the way you start is how it’s going to go next. I felt a huge load of responsibility.”

Rising rapidly, the Soyuz-U—powered uphill by the single RD-108 engine of its core stage and the RD-107 engines of its four strap-on boosters—exceeded 1,100 mph (1,770 km/h) within a minute of clearing the tower.

As they ascended, television images of Shepherd revealed him to be pumping his fist. “As a crew, we had waited a long time to get to that point in life, where this is actually happening,” he recalled, “and I was very keen to emphasize, you know, Let’s go get this done!”

At T+118 seconds, the tapering boosters were jettisoned, leaving the core alone to continue the boost into low-Earth orbit. By two minutes, Gidzenko, Krikalev and Shepherd had surpassed 3,350 mph (5,390 km/h) and, shortly thereafter, the escape tower and launch shroud were jettisoned, exposing Soyuz TM-31 to the near-vacuum of the rarefied high atmosphere.

A little less than five minutes since leaving the desolate steppe of Central Asia, the core booster was jettisoned at an altitude of 105 miles (170 km) and the third and final stage ignited, accelerating the Soyuz to a velocity of more than 13,420 mph (21,600 km/h).

By the time it separated, about nine minutes into the flight, Gidzenko, Krikalev and Shepherd were in an orbit of 144 x 113 miles (233 x 182 km), inclined 51.6 degrees to the equator. They deployed their craft’s communications and navigation antennas and electricity-generating solar arrays and, 90 minutes later, opened the hatch between Soyuz TM-31’s cramped Descent Module and the slightly roomier Orbital Module.

The crew spent a standard two days in transit, before Gidzenko oversaw a smooth, automated docking at the aft longitudinal port of the station’s Zvezda module at 2:21 p.m. Baikonur time (4:21 a.m. EDT) on 2 November. At the time of Contact and Capture, Soyuz TM-31 and the ISS were orbiting high above central Kazakhstan. An hour later, at 3:23 p.m. Baikonur time (5:23 a.m. EDT), the hatch was opened into Zvezda’s main compartment, with Gidzenko and Krikalev entering first, followed by Shepherd, who had to prepare tools to sample the station’s atmosphere and collect gas specimens.

“I think Sergei was the first guy in,” Shepherd chuckled later, “but then there was kind of a very busy scramble to do the initial things that we had to do and, particularly, to find the TV hook-up and the TV cable so that we could give you that downlink. We were really close to the wire getting all that rigged and happy and we almost missed it.”

The trio clasped hands in unison, although Shepherd reflected that they were too busy to regard themselves as pioneers at that time. “After the downlink was done, we just kind of all sat back and said, ‘Okay, we’ll call it a day’, because it was very hectic.”

For Krikalev, it represented a historic moment, too, but it was actually the second time that he had opened the hatches to the ISS, having also flown on STS-88—the inaugural shuttle assembly mission—back in December 1998, during which he and Bob Cabana had opened the hatches between the newly installed Unity node and the Russian-built Zarya control module.

Asked about whether he considered himself to be a pioneer, Krikalev’s thinking mirrored that of Shepherd, that their arrival was too busy, bringing the infant station and its systems to life. It was not like his two previous long-duration increments aboard Mir, both of which had brought him to an already fully functional orbital outpost. “At that moment, we were thinking of the present,” he said, “although, subconsciously, we understood that was a certain threshold we were supposed to cross.”

There could be no denying that it was a historic occasion. Although Soviet and Russian cosmonauts had occupied the Mir space station continuously from September 1989 through August 1999—more than 3,600 days—it was expected that the ISS era would usher in an unbroken new age of human habitation of the heavens. “If all goes well on this and future missions,” NASA explained in a pre-launch press release, “30 October 2000 will be the last day on which there were no human beings in space.”

And notwithstanding the trials and tribulations and tragedies and geopolitical difficulties which befell the project in the years which followed, those words have remained true to this very day.

The second part of this two-part Expedition 1 commemorative article will appear on Monday.

.

.

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook and Twitter!

.

.

What a great blast from the past! I was so lucky to be there and follow the crew around for Exp-1. Trip of a lifetime.