More than three months since its most recent mission, United Launch Alliance (ULA) plans to fly another gargantuan Delta IV Heavy rocket later this spring to deliver the highly secretive NROL-82 payload to orbit on behalf of the National Reconnaissance Office. Earlier this week, the Centennial, Colo.-headquartered organization announced that it had completed a customary Wet Dress Rehearsal (WDR) of the triple-barreled booster at Space Launch Complex (SLC)-6 at Vandenberg Air Force Base, Calif. A precise launch date for ULA’s 13th Delta IV Heavy flight and its 31st mission for the National Reconnaissance Office will be determined closer to the time.

Having flown only six times last year—flying five missions with its venerable Atlas V and the Delta IV Heavy just once—ULA aimed for an increased cadence of launches in 2021, spearheaded by the maiden voyage of the Vulcan-Centaur heavylifter.

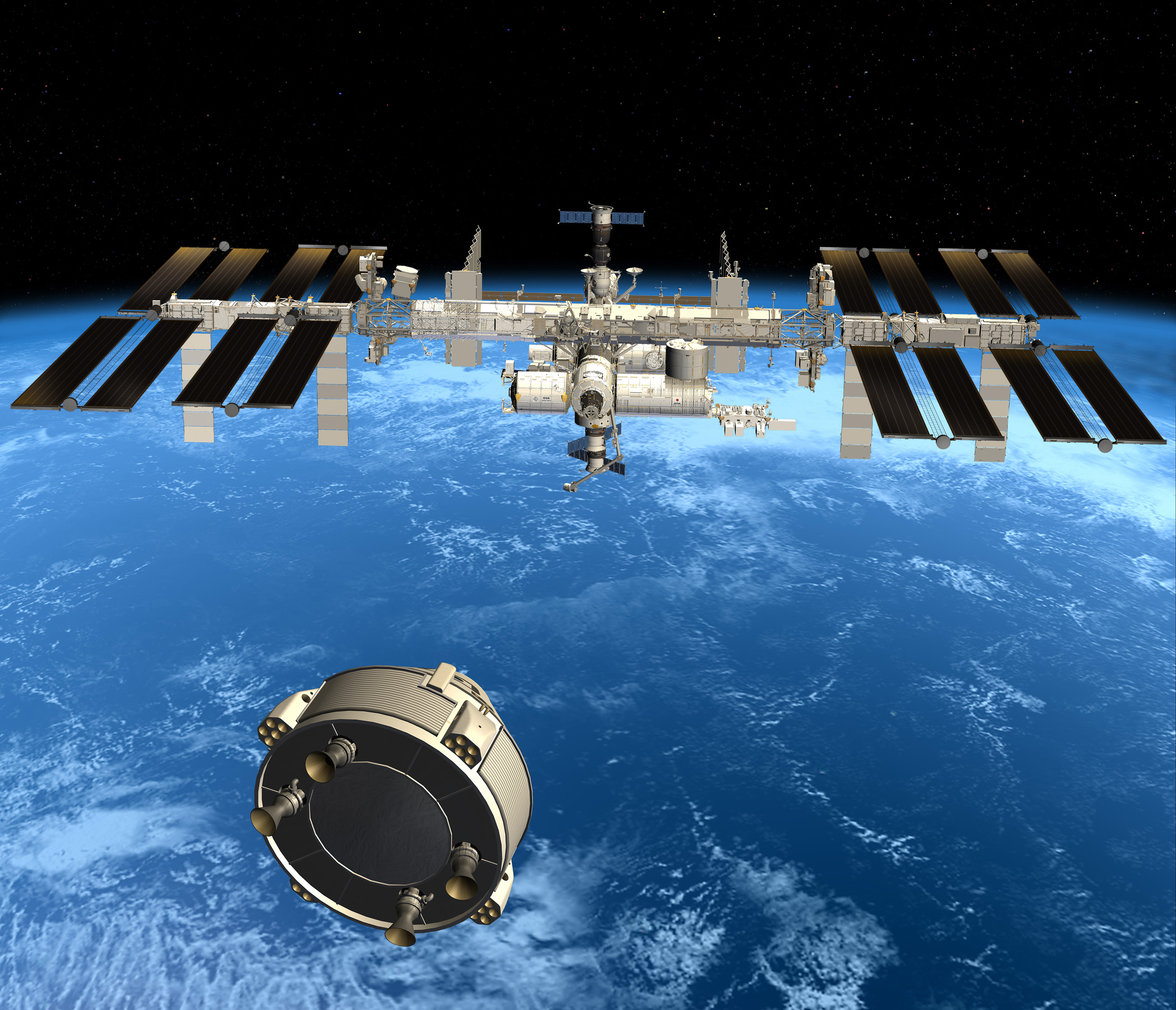

But delays to the Department of Defense’s Space Test Program (STP)-3 mission for “launch readiness” evaluations and with the second uncrewed Orbital Flight Test (OFT-2) of Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner to the International Space Station (ISS) having moved from March into April and now categorized as “Under Review”, the first quarter of the year has proved a launchless one for ULA. It remains to be seen if the first horse out of the gate will be OFT-2 from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Fla., or NROL-82 from the soon-to-be-renamed Vandenberg Space Force Base, Calif.

The giant Delta IV Heavy, which is composed of three Common Booster Cores (CBCs), bolted together, has flown 12 times between December 2004 and the long-delayed flight of the highly classified NROL-44 mission last December. Its launches have been conducted either from Space Launch Complex (SLC)-37B at the Cape or from SLC-6 at Vandenberg.

And it was the most powerful active operational rocket in the world until the arrival of SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy in February 2018. At liftoff, its three Aerojet Rocketdyne RS-68 engines produce an estimated 2.1 million pounds (1.1 million kg) of thrust and can lift up to 63,470 pounds (28,790 kg) into low-Earth orbit and as much as 14,880 pounds (6,750 kg) directly to Geostationary Earth Orbit (GEO).

Although its maiden test flight in December 2004 suffered a premature shutdown of one CBC, its subsequent missions enjoyed impeccable levels of success. The Delta IV Heavy lofted what is believed to have been the final Defense Support Program (DSP) early-warning satellite, NASA’s Parker Solar Probe, eight reconnaissance/intelligence payloads for the National Reconnaissance Office and the inaugural voyage of the Orion spacecraft on Exploration Flight Test (EFT)-1 in December 2014.

Only four more missions—two from Vandenberg and two from the Cape—remain on the booster’s books, as ULA aims to phase out and retire the expensive Delta product-line by the middle of the present decade. In September 2019, the Space and Missile Systems Center (SMC) at Los Angeles Air Force Base in El Segundo, Calif., in partnership with the National Reconnaissance Office, awarded a sole-source, five-year $1.18 billion Firm-Fixed Price (FFP) contract modification to ULA for Launch Operations Support (LOPS) for the launches of NROL-82 and four other missions on the final flights of the Delta IV Heavy. One of those launches, NROL-44, took place last December.

And preparations for the first of the four remaining missions, NROL-82, got underway last April when the three 134-foot-tall (40.5-meter) CBCs arrived at Vandenberg aboard ULA’s RocketShip vessel and were transported to the Horizontal Integration Facility (HIF) for several months of configuration and erection in SLC-6. Launch was originally targeted for the fourth quarter of 2020, although four months of agonizing delays to NROL-44 between August and December pushed this hope inexorably to the right.

Last month, ULA confirmed that the Delta IV Heavy for the NROL-82 mission had been rolled out from the HIF to the SLC-6 pad surface, securely fastened in place by a dozen explosive bolts to the structural base furnished by its Launch Mate Unit (LMU). The horizontal rollout of the booster (minus its payload fairing) took place atop a 36-wheel diesel-powered transporter on 15 February and the stack—which stands 170 feet (51.8 meters) tall, inclusive of its Delta Cryogenic Second Stage (DCSS)—was raised to the vertical the next day. It was then secured inside the pad’s Mobile Assembly Shelter, affording it protection from weather and the elements.

Earlier this week, ULA announced that it had concluded the customary Wet Dress Rehearsal (WDR) for the NROL-82 mission, in which the Mobile Service Tower (MST) at SLC-6 was rolled back from the vehicle and the site configured for fueling. WDRs are key pre-flight milestones performed to mitigate any issues ahead of launch day. They are typically executed prior to missions with narrow “launch windows” or at the request of their payload’s primary customer. In NROL-82’s case, the WDR involved loading all three CBCs with 440,000 pounds (200,000 kg) of liquid oxygen and hydrogen propellants, then counting down through a simulated Terminal Count to a cutoff point at T-10 seconds.

“Wet Dress Rehearsals are completed at customer request,” ULA’s Heather McFarland previously told AmericaSpace. “NRO missions typically have WDRs.”

When the NROL-82 payload is attached to the top of the Delta IV Heavy, the stack will rise 235 feet (72 meters) above the pad surface. The nature of the payload remains highly classified, although it has been suggested that it might be a KH-11 Kennen reconnaissance satellite, weighing up to 41,900 pounds (19,000 kg).

This class of satellites—of which another recent Delta IV Heavy payload, NROL-71, is also believed to have been one—are thought to operate in slightly elliptical orbits at an altitude of 160 x 620 miles (260 km x 1,000 km). They are thought to possess eight-foot-wide (2.4-meter) primary mirrors which afford them a ground-imaging capability of less than six inches (15 cm).

From a purely aesthetic point of view, watching the Delta IV Heavy launch is comparable to the magnificent Saturn V. Pure, raw power. And credit obviously goes to the engineers and scientists who designed and built these incredible machines.