Twenty years ago this morning, Columbia roared into space on what would be her last fully successful mission, STS-109. It was the 27th voyage of a vehicle which had ushered in the Space Shuttle Program, way back in April 1981, and gone on to secure a raft of other accomplishments: becoming the first spacecraft to return to low-Earth orbit with a crew, the first to deploy large communications satellites, the first to carry Spacelab and the first to be commanded by a woman. During her career, Columbia flew the shortest and longest shuttle missions and in March 2002—only a few months before her untimely demise—she flew to her highest altitude to service the Hubble Space Telescope.

Selection of her crew had gotten underway in September 2000, when spacewalkers Jim Newman, Mike Massimino, Rick Linnehan and veteran “Hubble Hugger” John Grunsfeld were assigned to STS-109. Working in two alternating pairs, they would execute five complex sessions of Extravehicular Activity (EVA) to replace the telescope’s aging solar arrays and fit new science instruments.

Six months later, in March 2001, the remainder of the crew was announced. Commanding STS-109 would be Scott Altman, joined by pilot Duane “Digger” Carey and flight engineer and Remote Manipulator System (RMS) mechanical arm operator Nancy Currie.

Officially, STS-109 was the fourth Hubble Space Telescope Servicing Mission yet was internally designated “HST SM-3B” by NASA, since it represented the second half of what was originally intended as a single shuttle flight.

Planned for June 2000—with a record-breaking six EVAs—that flight was necessarily split into two halves following a spate of failures on Hubble in the spring and early fall of 1999. As such, SM-3A flew in December 1999 and SM-3B would follow a couple years later. Grunsfeld was assigned to both missions to provide continuity.

Priority-wise, the STS-109 astronauts would replace Hubble’s Power Control Unit (PCU), in what NASA described as nothing less than “open-heart surgery” on the showpiece observatory. They would also fit a new Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS) and a cryocooler to support the Near-Infrared Camera and Multi-Object Spectrometer (NICMOS), the latter of which had run out of liquid nitrogen coolant.

Additional tasks including removing Hubble’s window-blind-like solar arrays with smaller, higher-capacity, rigidized ones. For more than a year, Grunsfeld, Linnehan, Newman and Massimino devoted at least 12 underwater training hours for every hour of their planned 30 hours of EVA.

Originally scheduled to fly in November 2001, delays in getting Columbia flight-ready after two years of refurbishment pushed the launch into February 2002 and finally the opening day of March. And in spite of dire predictions that a broken deck of cloud could scupper the launch attempt, all went smoothly.

“On board Columbia, we worked through our procedures down to the last couple of minutes,” Grunsfeld wrote in a diary entry. “Then, it was up to the computers on Columbia, the main engines and finally the boosters. In the last six seconds, the main engines announced that they were ready to rock and roll.”

Liftoff occurred at 6:22 a.m. EST, right on the opening of a 62-minute “window” and STS-109 rose on a pillar of flame into the pre-dawn darkness. From the pilot’s seat, Carey, a “rookie” astronaut, noticed how hard it was to speak. He had to adopt a sort of guttural grunt at the high-G phases of ascent.

But he had no trouble reaching for switches. High above them, and two days’ travel away, was Hubble, sitting at an altitude of 360 miles (580 kilometers), waiting for its next human visitors.

But all was not well with Columbia. Less than 90 minutes after launch, her payload bay doors were opened to reveal sluggish performance from one of two Freon coolant loops. A small shard of foreign debris had gotten stuck in the loop and raised the specter of a premature return to Earth.

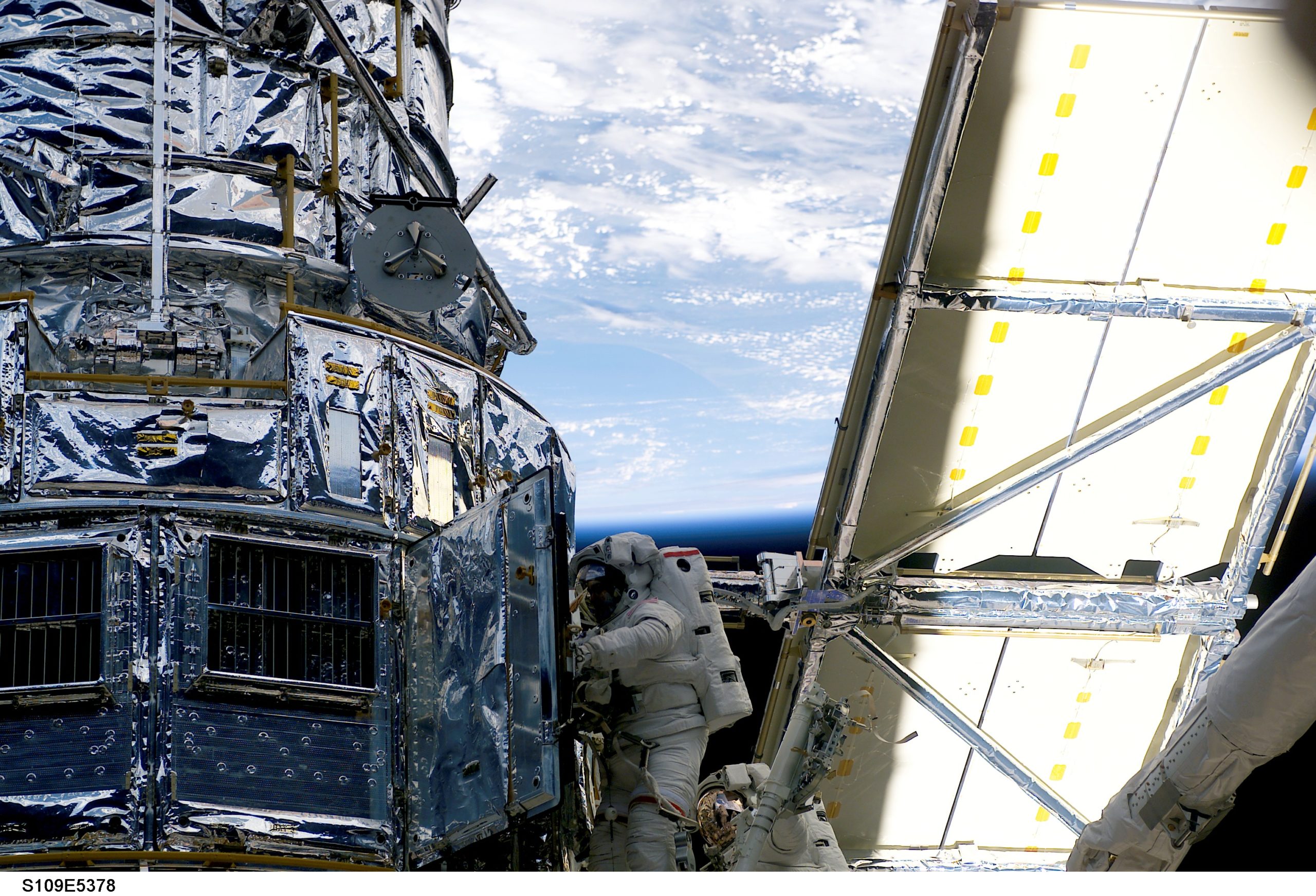

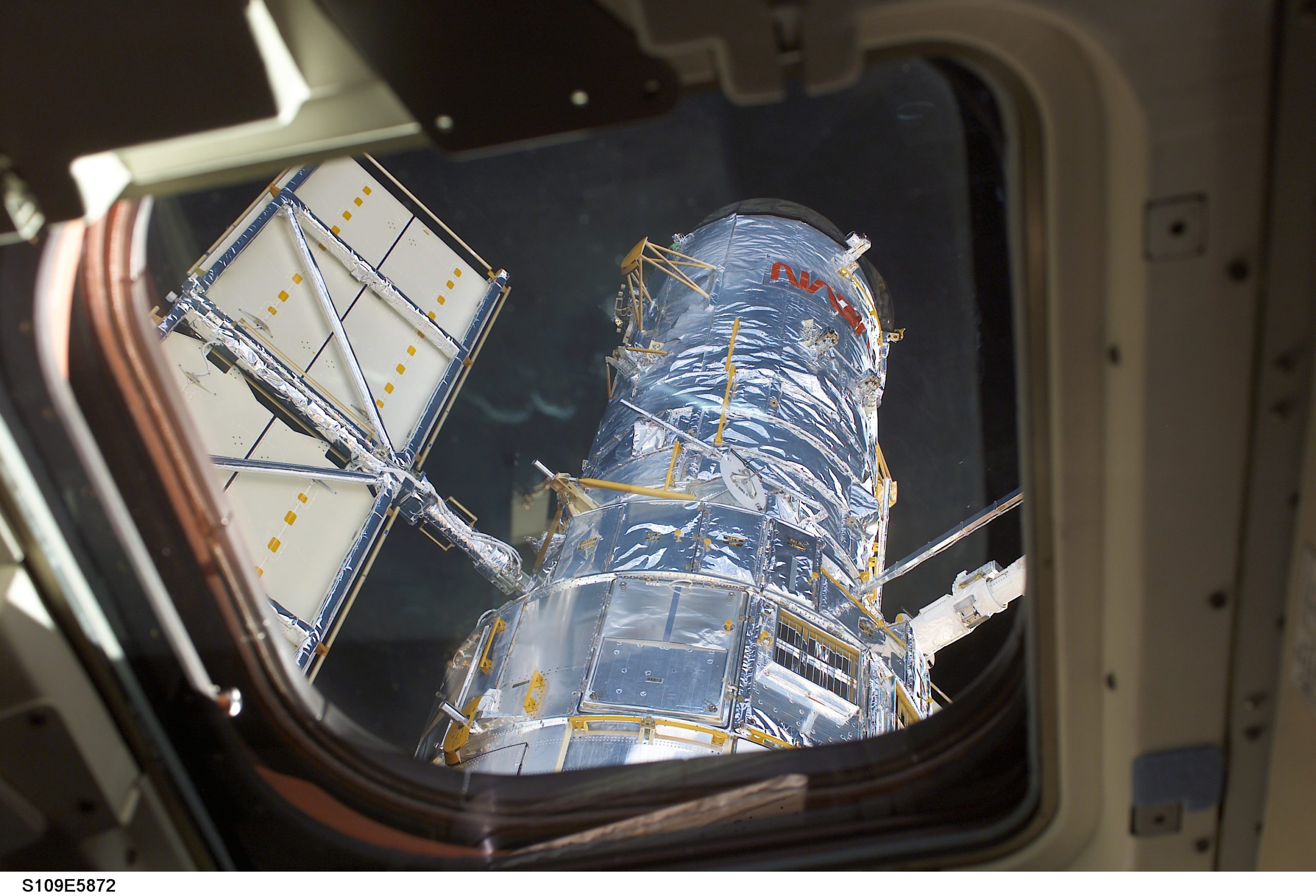

Fortunately, this did not prove necessary and early on 3 March the shuttle rendezvoused with Hubble and Currie grappled the 43-foot-tall (13-meter) telescope with the RMS mechanical arm and anchored it in the bay.

“Houston,” radioed Altman, “we have Hubble on the arm!”

“Copy, Scooter,” replied Capcom Mario Runco. “Outstanding work.”

Ahead lay five challenging EVAs, each baselined for six hours. For EVA-1, Grunsfeld and Linnehan would swap out the first of Hubble’s solar arrays. Then on EVA-2, Newman and Massimino would repeat the work for the second array. Each of the old arrays stood 39 feet (12 meters) tall and both were replaced without incident.

By March 2002, after almost a decade in orbit, they had degraded to provide only 63 percent of their original power output. The new, rigidized arrays, which folded out like the halves of a book, provided 30 percent more power, yielding 5,270 watts as opposed to 4,600 watts of their predecessors.

Grunsfeld was the only member of the STS-109 crew who had visited Hubble before; he would go on to fly the final servicing mission, STS-125 in May 2009, and today stands as the only human to have worked on the telescope in orbit three times. He introduced himself to “Mr. Hubble”, then declared that he had come “to give you more power to see the planets, stars and the Universe”.

Without further ado, Grunsfeld and Linnehan marched through the removal of the starboard-side array, stowed it and installed a diode box to ensure that power from new array flowed directly to the telescope’s batteries. Next morning, Newman and Massimino set to work on the port-side array, then replaced a reaction wheel which encountered difficulties a few months earlier. Validation tests from the Space Telescope Operations Control Center at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) in Greenbelt, Md., confirmed that both arrays and the reaction wheel were behaving as expected.

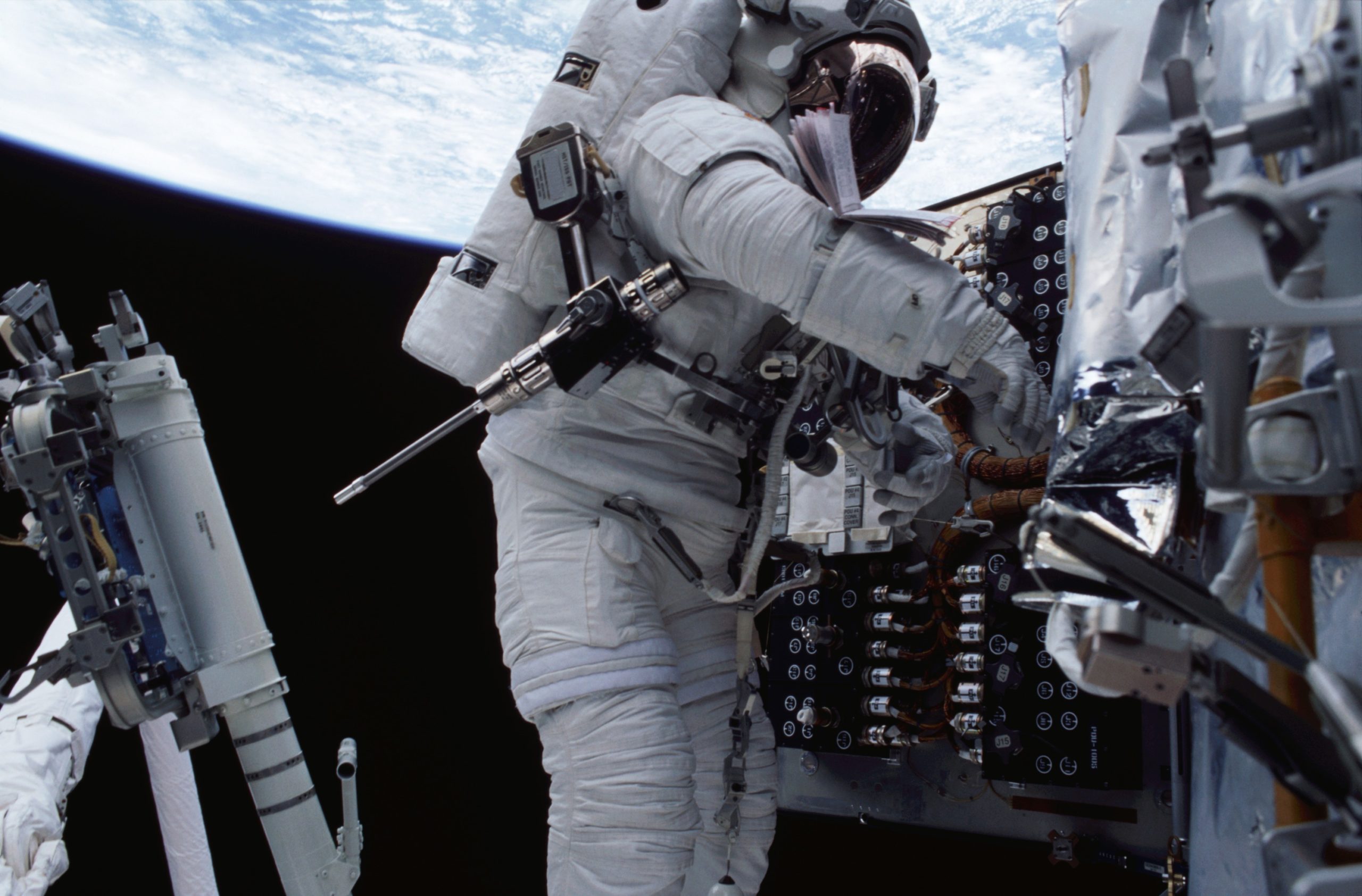

Next up, on EVA-3, Grunsfeld and Linnehan replaced the PCU, in a campaign whose complexity was likened to open-heart surgery. The day began ominously, with a water leak from Grunsfeld’s space suit, requiring him to swap it for a backup suit before the spacewalk began.

Eventually, two hours later than planned, the astronauts emerged from Columbia’s airlock and got to work. Delicately, they cut off power to Hubble’s six batteries, setting off a time-critical eight hours to complete the PCU changeout.

Complicating the procedure was the bulkiness of the cables, which made the 36 electrical connectors extremely difficult to reach. In fact, they were so tightly spaced that Grunsfeld and Linnehan needed to use a wrench, rather than their gloved hands, to get to them. Five hours into EVA-3, the PCU replacement was complete.

“You did it, buddy!” exulted Linnehan. “You did it!”

It was truly a significant moment. Although Hubble had been partially powered-down during STS-61, the first servicing mission in December 1993, a total shutdown of the telescope for several hours had not been attempted prior to SM-3B. Altman’s crew were certainly relieved when Runco came back with a post-operative report. “Columbia, Houston,” he told them. “We have a heartbeat!”

In what were described as “masterful performances”, the tone had been set for the remainder of the mission. Before launch, Grunsfeld joked that failure would mean he could never show his face at meetings of the American Astronomical Society (AAS) again; fortunately, that possibility was now averted.

During EVA-4, Newman and Massimino exchanged Hubble’s instruments. They pulled out the Faint Object Camera (FOC)—its sole remaining “original” instrument, in place since the telescope’s launch—and replaced it with the Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS). The new camera would cover significantly broader patches of the sky with greater clarity and speed than had previously been achievable.

With 80 percent of the mission complete, only EVA-5 now remained. And for Carey, there simply was not the option of “coasting” at this stage. He remembered some advice from Nancy Currie: she could only relax when she was outside the shuttle, in the bus, heading back to crew quarters, after landing.

“One of the main challenges on the mission is to keep that mental focus,” said Carey, “to wake up each morning and say: Okay, this is the big day! And then waking up the next morning and having that same attitude.”

Such an attitude pushed the crew through Grunsfeld and Linnehan’s EVA-5, which saw the installation of a cryocooler to bring NICMOS—out of service since early 1999—back to life. At the end of the spacewalk, Grunsfeld gave the telescope a farewell tap, convinced that he would never see the telescope again.

“But I have been touched by its magic,” he said, “and changed forever.” Little did Grunsfeld know that he would go on to play a major role in developing the final shuttle mission to Hubble. And in May 2009, he wound up flying to the telescope again.

With 35 hours and 55 minutes of spacewalking completed during STS-109, a new record had been established for servicing Hubble. In the meantime, STS-109 was nearing its conclusion.

A rejuvenated Hubble was deployed back into space on 9 March 2002 and Columbia herself returned to Earth a few days later. “Wheels Stop, KSC,” radioed Altman, as he guided his ship to a smooth halt on the Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF) at the Kennedy Space Center on the 12th.

It was Columbia’s last successful homecoming.

During descent, Linnehan—seated on the shuttle’s aft flight deck—observed the glowing trail of super-heated plasma, stretching behind them, as they plunged back to Earth. He managed to acquire the view by means of a hand-held mirror.

At one point in the descent, he offered Carey the chance to look in the mirror and see Columbia’s white-hot vertical stabilizer. Carey politely declined.

“No thanks, buddy,” he told Linnehan. “Some things you just don’t want to see!”

STS-109 was lucky. On Columbia’s next flight, her luck tragically ran out.