Three decades ago today, Columbia—the oldest and first-flown of NASA’s Space Shuttle fleet—stood patiently ready on historic Pad 39A at Florida’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC), awaiting her 14th launch. Devoted to a variety of U.S. and German research experiment, the Spacelab-D2 mission had been delayed repeatedly in the wake of the January 1986 Challenger tragedy and had been postponed by more than a month from her original February 1993 placeholder date, due to mechanical problems with Columbia herself. But on 22 March 1993, the gremlins of misfortune would have one final, dramatic card to play.

Early that morning, the seven STS-55 astronauts—Commander Steve Nagel, Pilot Tom Henricks, Payload Commander Jerry Ross, Mission Specialists Charlie Precourt and Bernard Harris and German Payload Specialists Ulrich Walter and Hans Schlegel—departed the Operations & Checkout Building at KSC, bound for the pad. It would prove to be one of the most hazardous shuttle launch countdowns ever endured.

The nine-day mission had been beset by problems since the dawn of the year. In January, suspicions were raised that Columbia’s three Space Shuttle Main Engines (SSMEs) might have obsolete tip-seal retainers on the blades of their High Pressure Oxygen Turbopumps (HPOTs). If the retainers were indeed of an older variety, flight rules dictated that they should be checked prior to each mission, but if they were newer-specification ones, they could fly safely several times, without inspection.

Certainty could not be established from the relevant engineering paperwork, so the retainers were removed and checked. It turned out that they were indeed of the “newer” variety, but by the time the three SSMEs were back in place the STS-55 launch had been unavoidably postponed from late February until the mid-March timeframe.

More trouble reared its head when a flex-hose in Columbia’s aft fuselage burst, spilling hydraulic fluid and triggering another delay. An Atlas I rocket poised on Space Launch Complex (SLC)-36B at neighboring Cape Canaveral Air Force Station—whose own launch with a military communications satellite would end in failure on 25 March—competed with the shuttle for Eastern Range tracking assets, ultimately pushing STS-55 deep into the second half of March.

Early on the 22nd, Nagel—a veteran of Spacelab-D1 in the fall of 1985 and therefore ideally placed to command the second German mission—led his men out to the pad and an anticipated T-0 at 9:51 a.m. EDT. The countdown proceeded smoothly and at T-31 seconds, as intended, Columbia’s computers assumed primary control from the Ground Launch Sequencer (GLS).

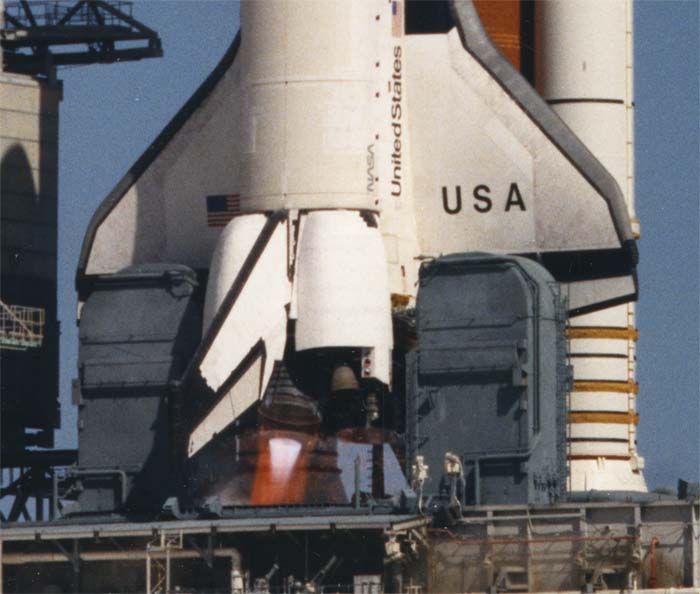

Six and a half seconds before launch, the ignition sequence of the SSMEs got underway with its familiar, low-pitched rumble. But within three seconds, all three shut down.

It was later determined that a liquid oxygen preburner check valve in the No. 3 engine had leaked in the final seconds, causing its purge system to be pressurized above the maximum redline of 50 psi. With the No. 3 engine having thus incompletely ignited, Columbia’s computers commanded all three to shut down, in a Redundant Set Launch Sequencer (RSLS) abort. The cause was traced to a tiny shard of rubber, lodged in an engine valve.

With unburnt hydrogen still lingering underneath the hot engine bells, the risk of a fire or explosion was very real. Seconds after the shutdown, the launch pad’s “white room” was automatically moved into position, alongside Columbia’s crew access hatch, preparatory to an evacuation, known as a “Mode One Egress”.

Although the astronauts had trained to escape from a pad abort and slide to a fortified bunker, the danger of having them evacuate Columbia and run through an invisible hydrogen holocaust prompted controllers to instruct them to remain aboard the orbiter. For 40 tense minutes, Nagel and his crew remained strapped into their seats as ground personnel deactivated all electronic components.

Paramedics were rushed to the pad as a precautionary measure, but for the astronauts all was well—albeit eerily still—in the swaying cabin. “I’d convinced myself,” Nagel said, “and all my crew that we were going to fly.” When the brief noise of the engines died, he called over the intercom to announce the abort to his crewmates.

“I wouldn’t call it fear,” he said later about those adrenaline-charged moments. “There’s a couple of moments wondering what’s happened, because all you see on-board are red lights, indicating an engine shutdown. You know the computers shut down the engines, but you don’t know why or exactly what went wrong with them.”

The situation was equally tense in the Launch Control Center (LCC), where ashen-faced Launch Director Bob Sieck watched the proceedings. “Your initial reaction,” he said later, “is to make sure there are no fuel leaks or that there’s nothing that’s broken that’s causing a hazardous situation.

“Really, it was one of those nice, boring countdowns until the last few seconds,” he continued. “What did work, and worked very well, were the safety systems on-board. As a result, the crew is safe and the vehicle is on the pad and safe as well.”

Nonetheless, the STS-55 crew emerged from the orbiter looking visibly shaken by the incident. A month would elapse before Columbia rocketed smoothly into orbit on 26 April 1993, but the RSLS abort suffered by Steve Nagel and his men provided a stark reminder of the inherent dangers involved in launching shuttle crews into orbit.

One Comment

One Ping

Pingback:“Sure Hope I Like This”: Remembering a Complex Shuttle Mission, 30 Years On - AmericaSpace