Thirty years ago, an unusual conversation was had between a grocery store shopper and one of his friends. The pair were using amateur radio to discuss the progress of the second German Spacelab mission, underway at that very moment aboard shuttle Columbia. Nothing unusual about that, one might think, except that the shopper’s “friend” happened to be NASA astronaut Steve Nagel, the shuttle commander, who had arranged the call via a colleague in Mission Control before Columbia’s 26 April 1993 launch.

The two friends spoke for four or five minutes, their words crackling between low-Earth orbit and the grocery store’s parking lot. Bemused shoppers paused to listen. When the call ended, one of them approached Nagel’s friend.

“Who were you talking to?”

“If I told you,” the friend grinned, “you wouldn’t believe me!”

Launched three decades ago today, STS-55 was a half-billion-dollar scientific venture between the United States and the newly unified Federal Republic of Germany, utilizing Europe’s expansive Spacelab pressurized module in the shuttle’s payload bay. Designated “Spacelab-D2” (for “Deutschland”), the mission featured 88 experiments spanning life sciences, radiation physics, materials science and technology.

“I’m not fluent in German,” said STS-55 Payload Commander Jerry Ross. “Fortunately, most of the international science people work in English anyhow, because you’ve got all the other languages in Europe that have to find some common language, and fortunately, that’s it.

“I tried to learn some German, but I’m not good in foreign languages to start with,” Ross continued. “And trying to do all the other things I was doing, there wasn’t time to learn much German.”

An earlier mission, Spacelab-D1, had flown in the fall of 1985, only a few months before the Challenger disaster, although in the era prior to reunification it was sponsored principally by West Germany. Yet these two Spacelab flights were expected to pave the way for future collaborative research aboard Space Station Freedom, the precursor to today’s International Space Station (ISS).

For his part, Nagel had served as pilot on Spacelab-D1 and it therefore made sense for him to return to command the second mission. But the two flights were quite different in their scope, with Spacelab-D2 emphasizing a heavier bias towards life sciences.

As such, the Germans insisted that NASA assign a medical doctor, Bernard Harris. And the seven-man STS-55 crew was rounded out with a pair of German payload specialists, physicists Ulrich Walter and Hans Schlegel, plus pilot Tom Henricks and flight engineer Charlie Precourt.

The Germans were offered the chance to have an Extended Duration Orbiter (EDO) pallet on the mission, facilitating a flight several days longer than the manifested “baseline” of ten days, but this was turned down in favor of an experiment-laden platform at the rear of Columbia’s payload bay. That pallet featured a group of astronomy, atmospheric physics and materials science payloads, including a modular optoelectronic multispectral scanner to observe vegetation, rock and soil surface cover over the Americas and parts of Africa, as well as the Near East, India, South East Asia, Indonesia, Australia and the Pacific Islands.

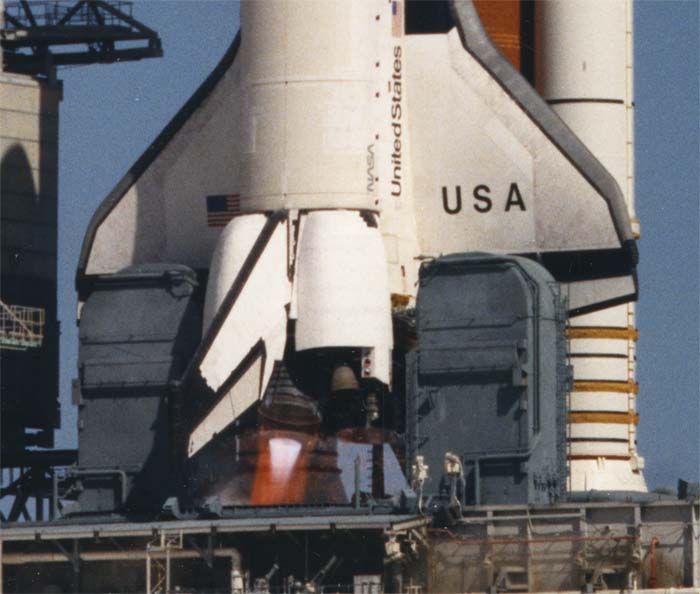

But preparations for STS-55 did not go well, as a raft of technical issues early in 1993 pushed the flight later into the spring. On 22 March, the shuttle’s engines dramatically shut down, seconds prior to liftoff, which enforced another month-long delay.

Finally, Columbia roared into orbit at 10:50 a.m. EDT on 26 April from historic Pad 39A at Florida’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC), setting a record of just nine days between the landing of one shuttle mission and the launch of another. “The experience of launch is spectacular,” Henricks noted at STS-55’s post-flight press conference. “It really is something.”

Upon reaching space, Nagel—who had flown with Ross on an earlier mission—was afforded the golden opportunity to play a prank on his long-time friend. During their last mission together, Ross performed a contingency spacewalk to help deploy the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory. Nagel had snapped a photograph of Ross’ face, pressed up against one of the shuttle’s flight deck windows, grinning at his crewmates inside the cabin.

Before STS-55, Nagel arranged for the picture to be reprinted and blown up to fit perfectly into one of Columbia’s aft flight deck windows. Those windows were covered with protective panels during launch and removed after the shuttle reached space.

Nagel knew that Ross would be the one to remove the panels and hoped that he would get a kick out of it. Indeed, when Ross pulled back the panel, he burst into spontaneous laughter at seeing his own face, staring back at him.

But there was little time for banter. Spacelab-D2 required around-the-clock operations and the astronauts swiftly separated into a pair of 12-hour shifts: a “red team”, consisting of Nagel, Henricks, Ross and Walter and a “blue team” of Precourt, Harris and Schlegel. But as the payload commander, Ross considered it his duty to ensure that the teams had time at shift changeovers to discuss experiments, problems, flight notes and to ascertain that the entire crew was getting enough rest.

Spacelab-D2’s 88 experiments ran the gamut from life sciences, biological sciences, materials and fluid physics, astronomy, Earth observations and technology. This included a six-jointed robotic arm with tactile and torque sensors, with almost 40 percent devoted to human studies and physiology.

The research was sponsored not only by Germany and the United States, but also included investigators from France and Japan. And in addition to NASA’s own Mission Control Center (MCC) at the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas, a Payload Operations Control Center (POCC) was run from the German city of Oberpfaffenhofen, near Munich.

Aside from a leak in a waste water tank, STS-55 proceeded without incident. Of greater concern, though, was an overheating science freezer on Columbia’s middeck, which forced the crew to move their biological samples over to a backup freezer.

“The freezers we were carrying…were failing at a pretty rapid clip,” Ross said later. “It became apparent to me that probably 40-50 percent of the science was counting on that freezer working and bringing back those samples that we collected.” On Ross’ advice, a backup freezer had been assigned to STS-55 and this proved highly fortuitous when the primary freezer overheated and eventually failed.

For his part, Nagel felt that fears of losing the biological samples factored into Mission Control’s decision to bring Columbia home on 6 May, after ten days, lest the backup freezer should also fail. Early in the mission, planners had conserved as much electrical power as possible, hopeful of squeezing an extra 24 hours onto the end of the flight and running STS-55 to as long as 11 days.

But it was not to be. Early on the 6th, the astronauts shut down the Spacelab-D2 module for the final time and prepared for re-entry. However, the first landing opportunity was waved off, due to unacceptable weather at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida.

And when conditions did not improve one orbit later, Nagel and his crew were directed instead to land at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. Columbia touched down safely at the Mojave Desert landing site at 7:29 a.m. PDT (10:29 a.m. EDT), wrapping up a mission less than one hour shy of ten full days.

Years later, Nagel—who died in 2014—was convinced that Columbia could have remained aloft for an additional day, but the importance of Spacelab-D2’s science (and the presence of just one surviving freezer) overruled such a move. “The Germans were hanging it all on one freezer to save these samples,” Nagel said, “and I’m sure that’s why, when it came time to land, we were weathered out of Florida and went to Edwards.”

Dear Ben,

this is Ulrich, one of the two German astronauts on STS-55. Thanks for giving this excellent throwback. The crew had a beautiful 25th anniversary tour in May 2018 through Germany, unfortunately without Steve who passed away earlier. We still meet yearly on ASE conferences, this year in Bursa/ Turkey.

Best

Ulrich Walter

STS- 55 Payload Specialist