Eighty-four days. A mere 12 weeks on Earth, 84 days was the exact time spent aloft by the record-setting final crew of America’s Skylab space station. It also marked the time elapsed between the landing and re-launch of shuttle Columbia in April and July 1997, which saw seven U.S. astronauts—Commander Jim Halsell, Pilot Susan Still, Mission Specialists Janice Voss, Mike Gernhardt and Don Thomas and Payload Specialists Greg Linteris and Roger Crouch—secure the empirical record for the shortest interval between returning from one space mission and launching on another. STS-83 was meant to last 16 days. It ended up lasting less than four.

In doing so, Halsell’s crew, who landed from STS-83 on 8 April 1997 and returned to orbit on STS-94 the following 1 July, surpassed the previous record-holding spacefarer, Steve Nagel, who secured 128 days between his own two shuttle flights in the summer and fall of 1985. In Halsell’s words, flying twice in such a short span of time was nothing less than “a marvelous, once-in-a-career opportunity”.

Launched on 4 April 1997, STS-83 was the Microgravity Science Laboratory (MSL-1) mission, devoted to materials research, combustion science and fluid physics, on the second-to-last voyage of Europe’s Spacelab pressurized module. With the International Space Station (ISS) on the horizon, many scientists were keenly aware that STS-83 was one of their final throws of the dice on the shuttle before the station came online.

The crew was highly experienced. In January 1996, aeronautical engineer Voss and materials science Thomas were announced, followed shortly afterwards by physicist Crouch and mechanical engineer Linteris. Working across two 12-hour shifts, the quartet would support over 25 experiments aboard MSL-1. At the end of May, Halsell, Still and Gernhardt were named to round out the STS-83 crew, with a targeted launch in spring 1997.

But in late January, only nine weeks before launch, came a potential showstopper. After completing an emergency egress training session at the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas, Thomas broke his ankle in a fall down some stairs. Fearful that he might not recover in time, NASA assigned astronaut Catherine “Cady” Coleman to train alongside him, ready to step into his shoes if needed.

By mid-March, Thomas was in “a period of pretty heavy physical therapy”, spending six hours daily walking in swimming pools, with and without his cast, to restore his mobility strength. “There’s no doubt in my mind,” he told journalists, “or the doctor’s mind, that I’ll be ready in time.”

Launch of STS-83 was postponed 24 hours from 3 to 4 April, due to an improperly insulated water coolant line in Columbia’s payload bay. With launch rescheduled for 2 p.m. EDT on the 4th, the only concern seemed to be a slight chance of rain showers triggered by sea breezes. Mission managers considered, then discarded, an option to fly an hour sooner than planned at 1:07 p.m. EDT to provide more daylight at the Transoceanic Abort Landing (TAL) site at Banjul in West Africa to alleviate concerns about delamination of a backup tracking antenna there.

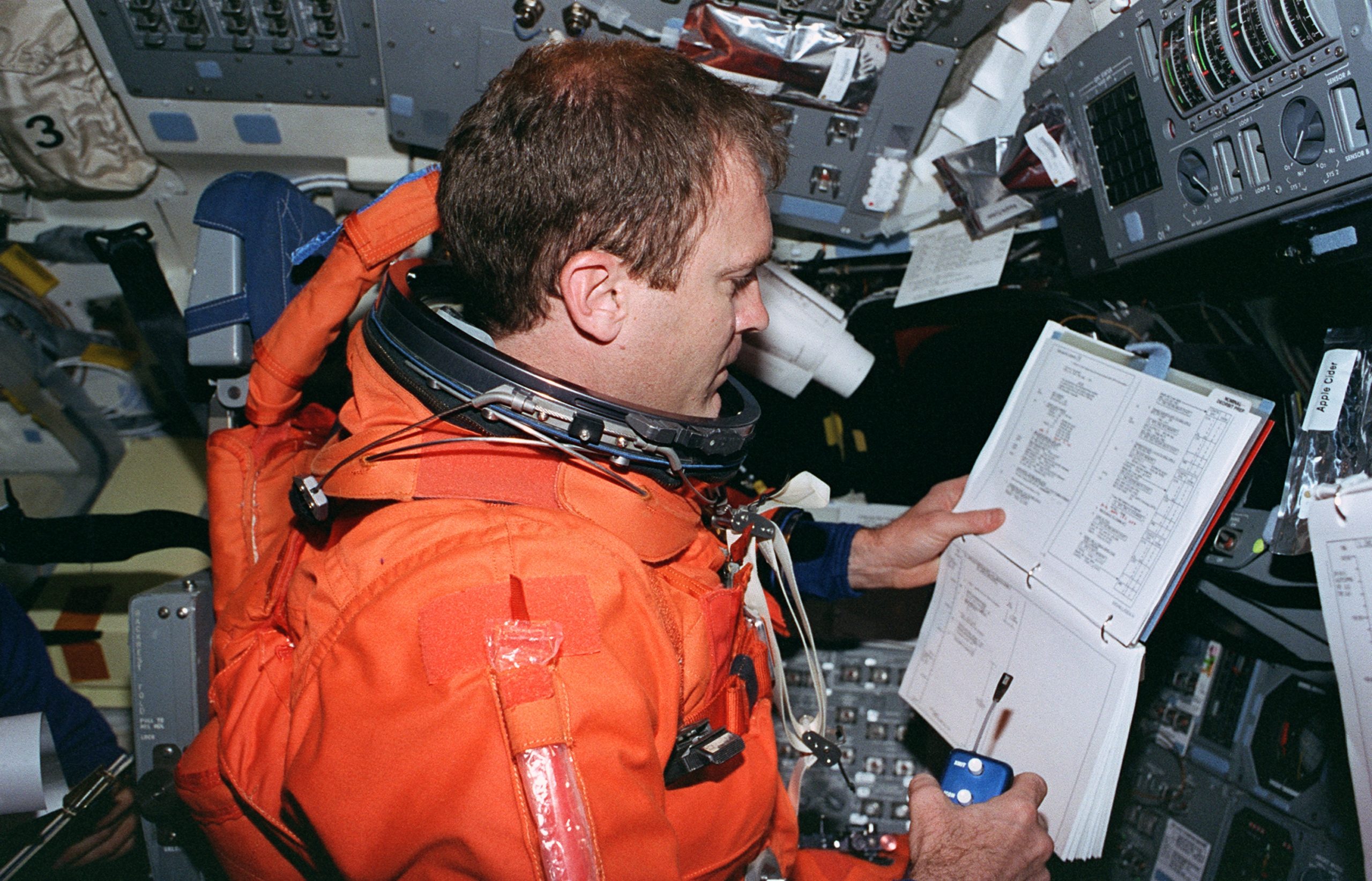

“Not nervous at all,” was the recollection of Still, who was making her first flight. “I’m mentally reviewing procedures and waiting with excitement for when I get to start moving switches in preparation for launch.” Following a slight delay in evacuating the closeout crew from the launch pad’s danger area and excessive oxygen concentrations in the payload bay, Columbia roared uphill at 2:20 p.m. EDT.

“A research bridge to the space benefits of tomorrow,” was the send-off remark from NASA’s launch commentator as NASA’s oldest shuttle—making her 22nd voyage into space since April 1981—speared toward an orbit of 186 miles (300 kilometers) above the Home Planet, inclined 28.5 degrees to the equator.

There was, Still said later, “no stopping us now”, and she recalled some surprise as the vibrations were lower than she had seen during training. “The acceleration off the launch pad was less than I’ve experienced catapulting off aircraft carriers,” she said, reflecting on her previous career as a Navy test pilot. “But soon, things got pretty exciting. When I started feeling the G-forces, pressing down on my chest, I knew I was accelerating faster than ever before. Zero to over 17,500 miles per hour, in only eight-and-a-half minutes. Now that’s pretty exciting!”

Two minutes into flight, as Columbia shed her twin Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs), a blinding flash of light swept across the forward windows. That generated a spontaneous scream of “Wow!” from the flight deck crew.

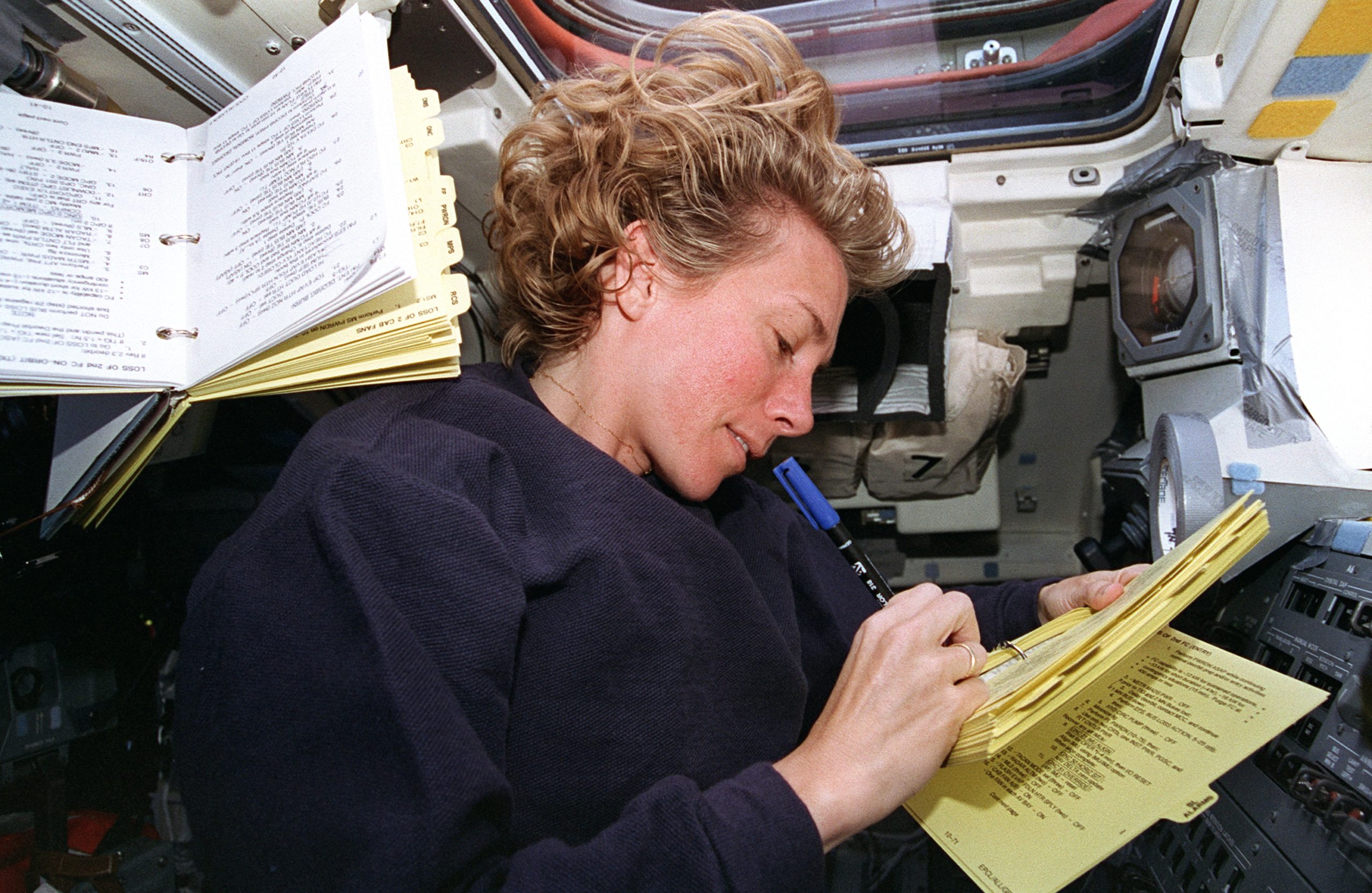

Within hours of reaching orbit, the STS-83 split into two shifts—with Halsell, Still, Thomas and Linteris on the “red” team and Gernhardt, Voss and Crouch on the “blue” team—either heading to bed or plunging into checklists to activate MSL-1. “Everything’s going great,” said MSL-1 Mission Manager Teresa Vanhooser of NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in Huntsville, Ala., as the lab came alive on the evening of 4 April. Sadly, her words proved distressingly prophetic, as the fortunes of STS-83 took a distinct turn for the worse.

Mission Control had begun to see erratic behavior in one of Columbia’s three power-producing fuel cells. Although a single cell could sustain on-orbit and landing operations, flight rules dictated that all three had to be functional for a mission to continue.

Each cell carried three “stacks”, made up of two banks of 16 cells each. In one of Fuel Cell No. 2’s stacks, the difference in output voltage between the two banks indicated an increase. The problem was spotted the night before Columbia launched but leveled-off and was considered an “in-family” glitch and cleared for flight. Late on 5 April, Halsell and Still adjusted the electrical system configuration to reduce demands on the ailing cell, thereby allowing Mission Control to stabilize and continue to monitor it.

Overnight, the rate of change in the cell slowed from five millivolts per hour to around two millivolts but continued to exhibit a slight upward trend. “There’s always a difference between the two halves of the stack,” Mission Operations Directorate (MOD) representative and former flight director Jeff Bantle told journalists, “but we’re noticing a changing difference. Actually that changing difference has leveled off a lot, so the degradation was greater the first 12 hours of the mission.”

If the difference between the two stacks increased as high as 300 millivolts—and it was pushing 250 by the night of the 5th—it could force the STS-83 crew to shut down Fuel Cell No. 2 entirely. “The concern is degradation in a single cell,” Bantle explained. “If it degrades enough, rather than getting power out from the cell, you would have power output into that cell. You could actually have crossover and localized heating, exchange of hydrogen and oxygen within the cell, and could even have a localized fire. That’s the very worst case. That’s why we have flight rules that are very conservative to try to avoid and try to shut down and safe a fuel cell before you would ever get to that point.”

At the Capcom’s console in Mission Control for much of this drama was Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield. Writing years later in his memoir An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth, Hadfield was initially convinced it was a sensor problem, rather than a glitch with the fuel cell itself. “But Flight Rules insisted the fuel cell had to be shut down,” he wrote, “and then, with only two fuel cells deemed fully operational, another flight rule kicked in: the mission had to be terminated.”

A manual purge of the cell by Halsell and Still proved fruitless and it was left to Hadfield to break the bad news. On the afternoon of 6 April, a Minimum Duration Flight (MDF) was declared and preparations kicked into high gear to bring Columbia back home on the 8th. “Listen, I know you just got up there,” Hadfield told Halsell, paraphrased in his memoir, “but you have to come on back. Starting now.”

Notwithstanding the crushing disappointment, Mission Control retained a sense of humor, by faxing the astronauts a tongue-in-cheek list of the Top Ten “real” reasons why they were coming home early. These included running out of “Columbian” coffee, forgetting to record the latest episode of Friends, forgetting to do their taxes before launch…and that the entire situation was just a horrid April Fool’s prank.

As the premature end of STS-83 neared, the crew and ground personnel worked together to devise an alternate flight plan. Fuel Cell No. 2 was shut down, as were other non-critical pieces of equipment, in order for science operations to continue. Lights were turned off inside the Spacelab module, forcing the astronauts to work by torchlight. It was a shock verging on disbelief that 16 days of carefully planned research was ruined.

Over the following 36 hours, the crew worked around the clock to complete a remarkable amount of research. Before the shuttle landed, informal discussions were already underway to refly the mission, later in 1997. “There were rumors already flying,” Thomas recounted on his website, OhioAstronaut.com, “that after fixing the problem NASA would be re-flying our crew in a few months to complete our Spacelab science mission. That definitely helped ease the sting of coming home early.”

Crewmate Roger Crouch agreed. “In some ways, this could make for a more meaningful flight in the long run,” he said, “but, certainly this one was a bummer!”

Columbia landed safely on Runway 15 of the Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF) at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida at 1:33 p.m. EDT on 8 April, wrapping up a flight of just 95 hours in space. It was the fourth-shortest shuttle mission ever completed: surpassed by Columbia’s first two test-flights in April and November 1981 and by STS-51C, a classified voyage by Discovery in January 1985.

And as Halsell climbed out of his ship, he was approached by KSC Director Roy Bridges, who offered him a handshake and the words: “We’re going to try to give you an oil change and send you back.” Two weeks later, NASA announced that the mission would refly in early July 1997, taking on the next-available unused shuttle flight number of “STS-94”.

Thanks to the identical nature of the payload, a significant portion of post-flight processing was simplified. In fact, when Columbia prepared to fly again on the afternoon of 1 July a mere $55 million had been expended on her processing and £8.6 million on the turnaround of the MSL-1 payload itself.

The shuttle spent just 56 days in the Orbiter Processing Facility (OPF), less than two-thirds of what would ordinarily be required for flight-to-flight preparations. In order to allow for necessary tasks to take place—such as the replacement of two Auxiliary Power Units (APUs) and several Reaction Control System (RCS) thrusters—a number of structural inspections were deferred until Columbia’s next processing flow. Remarkably, this was the shortest turnaround for a single shuttle in the post-Challenger era. By 11 June 1997, the vehicle was back at Pad 39A, tracking an opening launch attempt on 1 July.

“Our approach,” said STS-83 and STS-94 Lead Flight Director Rob Kelso, “has been to treat this flight as a launch delay. The crew is exactly the same, the flight directors are all the same and the flight control team is almost identical. It’s a mirror-image flight in many respects.” Even the embroidered patch, worn by Halsell’s crew, was the same, albeit with a red border for STS-83 and a blue border for STS-94.

And at 12:50 p.m. EDT on 1 July 1997, just 84 days since their return from STS-83, Halsell and his six crewmates headed into orbit again.

“Thanks to the whole ascent team for getting us to a safe orbit,” said Still.

“It looks like Columbia’s performing like a champ,” raplied Capcom Dom Gorie.

This time around, she certainly was.

Lorem ipsum 123 789