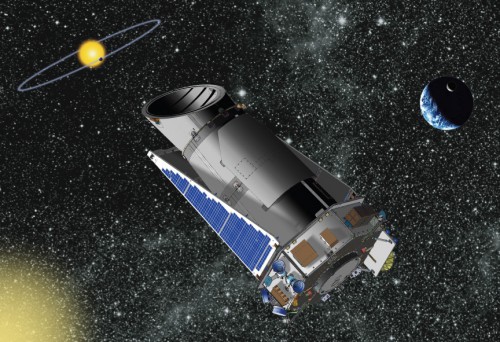

Launched on March 7, 2009, NASA’s Kepler space telescope, designed to hunt for Earth-sized planets orbiting other stars, has proved to be an outstanding success and has surpassed its initial planned lifetime of 3.5 years. But the recent failure of one of its three remaining reaction wheels—a fourth had stopped working earlier—has put the mission in jeopardy. In fact, it’s quite possible that Kepler has made its last planet-seeking observation. So what comes next?

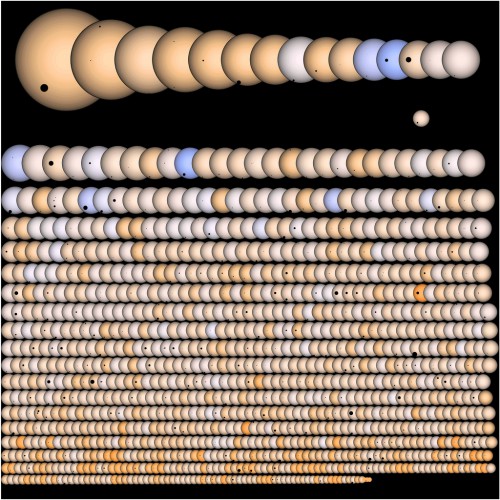

Kepler has amassed enough data to keep astronomers busy for another two years, sifting through the results it’s gathered for the tell-tale signals of exoplanets. The spacecraft had been focusing on one small patch of sky in the constellation Cygnus, using a sensitive photometer to continually monitor the brightness of over 145,000 stars in its field of view. Tiny variations in the light received from these stars could reveal a planet passing in front of—or transiting—a star’s disk as seen from Earth. Up to the present, Kepler has discovered 114 new planets and come up with an additional 2,740 planet candidates, which scientists must now look at carefully to confirm or reject.

Intriguingly, Kepler has spotted several Earth-like planets going around stars in their habitable zones—the orbital region in which conditions are right for liquid water to exist permanently on a planet’s surface. These worlds are therefore of high interest in the search for extraterrestrial life. The certain knowledge that such places exist, and are probably very common in the Galaxy, has spurred interest in building a new generation of planet-hunting instruments, both on the ground and in space.

A large number of ground-based projects to look for exoplanets are already running, and more are planned with the advent of a new generation of spectacularly large telescopes, such as the European Extremely Large Telescope (EELV), which will have a primary mirror 39.5 meters in diameter. With the EELV astronomers hope to be able to characterize the atmospheres of exoplanets and be able to directly image the larger ones and possibly even some of the Earth-sized ones.

In April 2013, NASA’s Astrophysics Explorer Program selected a mission called the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) for launch in 2017. This will use the same basic technique as Kepler to look for planets—the transit method—but will focus its attention on relatively nearby stars that are similar to the Sun. Unlike Kepler, which kept its gaze firmly in one direction, TESS will have an array of telescopes capable of searching virtually the entire sky, examining at least a million nearby stars for planets that are anything from roughly Earth-sized to gas giants. Its main goal will be to identify terrestrial planets in the habitable zones of stars on our cosmic doorstep.

Beyond TESS, plans are on the drawing board for more ambitious space-borne missions that will be able to learn more about the surfaces of these reasonably nearby, Earth-sized worlds—if they have large areas of water, ice, or land. With help from telescopes on the ground, it should be possible to discover the atmospheric composition of these planets, and then to launch still more powerful space missions to search specifically for signatures of life, such as the spectral fingerprints of biochemically significant substances like chlorophyll. Kepler has opened the door not only to a universe full of planets but, potentially, the discovery of life—maybe even intelligence—beyond the solar system.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter:@AmericaSpace

Kepler has blazed an important trail in mankind’s quest to find habitable planets. It is only logical that new generations of spacecraft with build upon the Kepler experience and allow scientists to find evidence of microbial life “out there.” It is exciting to contemplate!