NASA announced Tuesday, Sept. 10 that ground controllers have lost contact with its flagship comet-hunting probe Deep Impact, which is part of the Discovery Program managed at Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala. The probe hasn’t been heard from since its last transmission on Aug. 8. Since controllers only communicate with the probe weekly, it is estimated that communication was lost between Aug. 11 and Aug. 14. This mission is managed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL).

A JPL press release stated that mission controllers believe the problem has been caused by an anomaly with the vehicle’s computers, leaving them in a constant state of “reboot” (imagine your home computer starting over and over again, but never going to its operating system).

This situation means the spacecraft cannot send commands to its thrusters to fire and stay in a correct attitude, making it difficult to reestablish communication due to an inability to orient the vehicle’s antennas. In addition, the vehicle is powered by solar arrays, so its power situation is also unaccounted for, as the arrays are meant to be pointing their cells in one direction.

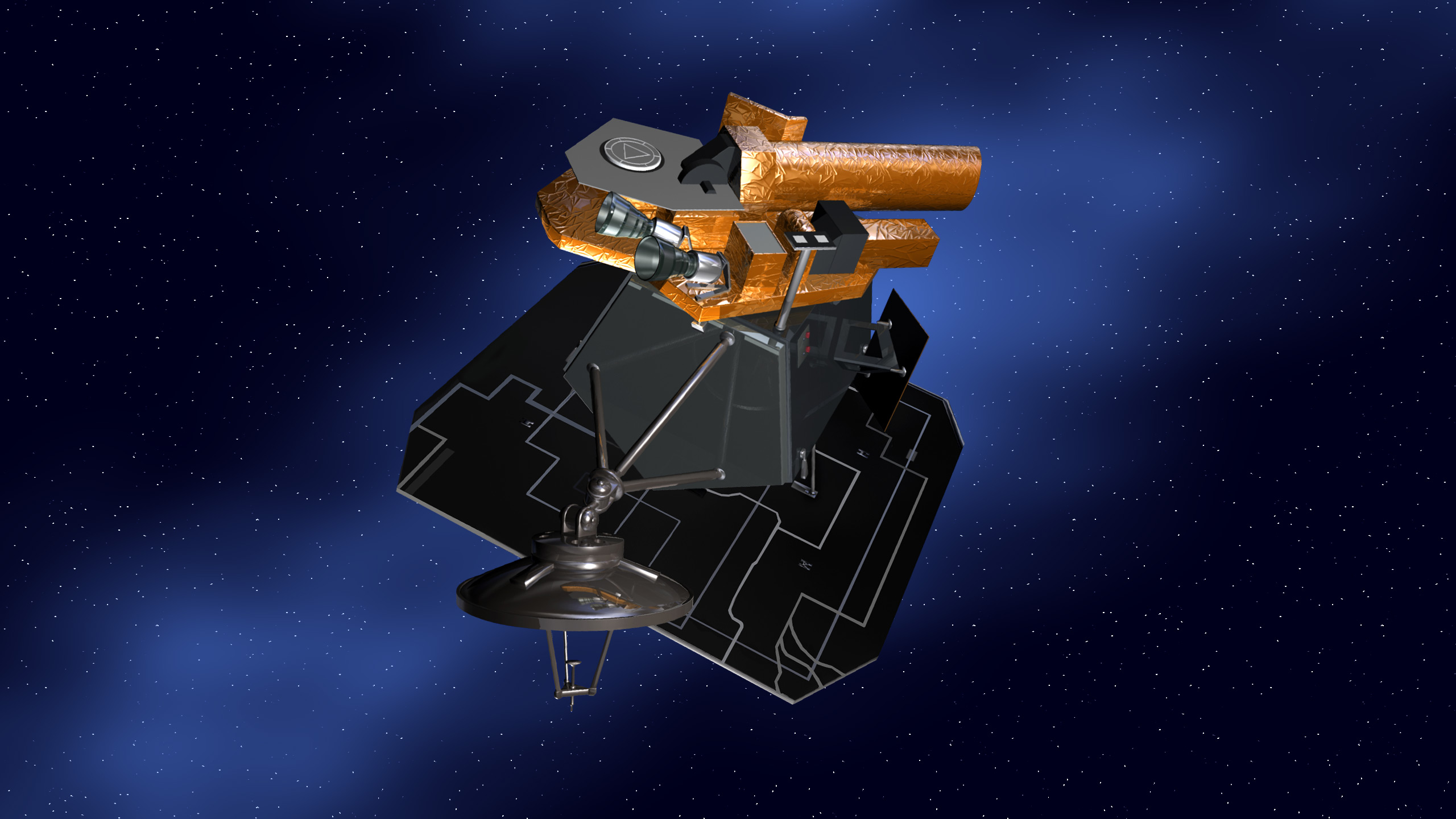

Deep Impact is the world’s supreme comet hunter, having traveled about 4.7 billion miles in space. It was launched on Jan. 12, 2005, on a Delta II rocket from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station. Following an initial issue following its launch (the spacecraft went into a “safe mode” after entering a heliocentric orbit), the problem was solved and Deep Impact was proven to be a fine workhorse.

After traveling a whopping 268 million miles to make contact (via an impactor tool) with comet Tempel 1 in July 2005, its extended mission saw the spacecraft fly past Earth and encounter comet Hartley 2 in November 2010. In January 2012, it imaged C/2009 P1 (Garradd). Most recently, in April, Deep Impact imaged comet ISON. It was slated to pass approximately 730,000 miles above our closest star, the Sun, in November.

The Deep Impact extended mission (EPOXI) website further stated that mission controllers are “now trying to determine how best to try to recover communication.” At the time of writing this piece, there is no definitive word on whether the spacecraft can be considered “lost.”

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Firstly they need to determine its dynamic attitude ie how is it tumbling. Then they can time their Commands to arrive at the optimum attitude (when there is max sun on the solar panels) to perform the required functions.

This is what we did to recover the ESA spacecraft OLYMPUS which went out of control in geostationary orbit in the 1990’s.

BTW I’m surprised there isn’t a count of the number of re-boots, which triggers the loading of a ‘safe’ software image when hitting a limit. Also that Time count roll-over wasn’t envisaged in the design.

These things are normal practice for Onboard Computer systems these days.

Stuart Hurst (Brit)