The recent geopolitical tensions resulting from the ongoing crisis between Russia and Ukraine have indirectly helped to reveal in a sobering fashion one of the major problems that has been plaguing the U.S. public space program for many years: the overall lack of foresight and national leadership.

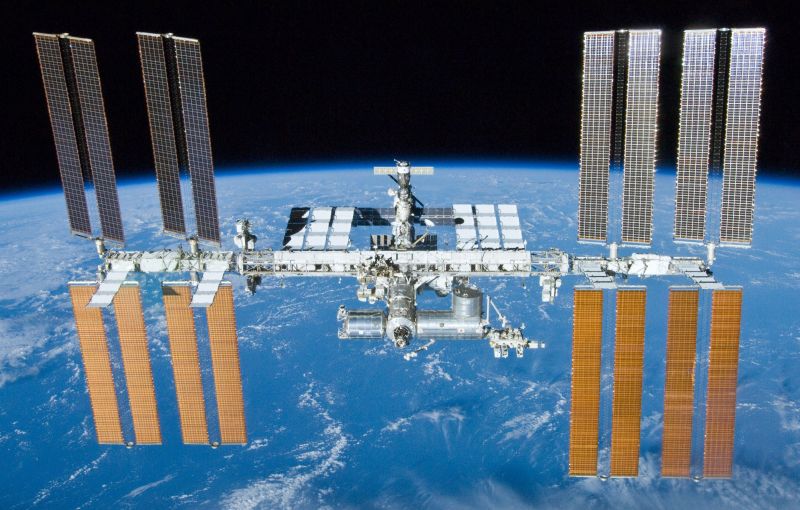

The deterioration in U.S.-Russian relationships that resulted from the annexation of Ukraine’s Crimea peninsula by Russia last month has awakened many in the U.S. to the implications of the lack of a domestic crew launch capability to low-Earth orbit, as evidenced in the various hearings that took place on Capitol Hill in recent weeks regarding NASA’s budget. Yet, despite the many rounds of finger-pointing between Congress and the White House over the issue, this state of affairs has resulted from a series of ill-fated and poorly thought-out decisions made in previous years by all interesting parties, including NASA’s leadership itself. These decisions left a lasting impact in a negative way, in almost every aspect of the space agency’s human spaceflight program, ranging from the ability to have regular access to the International Space Station, to setting realistic goals for deep space exploration beyond low-Earth orbit.

U.S. access to low-Earth orbit

With the retirement of the space shuttle in 2011, NASA has been entirely dependent on Russia ever since for transporting its astronauts to and from the ISS, onboard Russian Soyuz spaceships. Although the space agency had fostered the development of human-rated vehicles by private U.S. space companies under the Commercial Crew program since the shuttle’s retirement, the program hasn’t received adequate funding from Congress, which led to further delays in the development of domestic crew transportation services to the orbiting laboratory.

Russia’s actions in Crimea during the previous two months have received widespread condemnation in the West, with many countries imposing a series of diplomatic sanctions on the Russian Federation, including those that are its partners on the ISS program, like the U.S., Canada, and the countries of the European Union. While many have feared that these events could ultimately disrupt the normal operations onboard the ISS with Russia denying access to the orbiting laboratory to U.S. astronauts, NASA was quick to point out that such fears are unfounded and the relationships between the space agencies of the two countries continue to be harmonious.

Then, on April 2, the U.S. space agency posed its own sanctions on its Russian counterpart, by announcing that it was suspending communications with Russian government officials, due to the events in Crimea. Later the same day, the space agency released an official statement explaining the reasons for this action:

“Given Russia’s ongoing violation of Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity, NASA is suspending the majority of its ongoing engagements with the Russian Federation. NASA and Roscosmos will, however, continue to work together to maintain safe and continuous operation of the International Space Station. NASA is laser focused on a plan to return human spaceflight launches to American soil, and end our reliance on Russia to get into space. This has been a top priority of the Obama Administration’s for the past five years, and had our plan been fully funded, we would have returned American human spaceflight launches – and the jobs they support – back to the United States next year. With the reduced level of funding approved by Congress, we’re now looking at launching from U.S. soil in 2017. The choice here is between fully funding the plan to bring space launches back to America or continuing to send millions of dollars to the Russians. It’s that simple. The Obama Administration chooses to invest in America – and we are hopeful that Congress will do the same.”

In the week following the announcement, the majority of NASA’s ongoing engagements with Russia in space, like the operation of the ISS and the Russian-made Dynamic Albedo of Neutrons experiment, or DAN, onboard the Curiosity rover on Mars, as well as NASA’s participation in the upcoming 40th COSPAR Scientific Assembly scheduled to be held in Moscow later this year, were all exempted from this suspension of relationships between the two space agencies.

With almost every activity between NASA and Roscosmos essentially being uninterrupted by the ban, one has to wonder what exactly was the purpose of NASA’s announcement anyway. If the rationale was to accelerate development for Commercial Crew through the appropriation of more funding for the program, it’s a rationale that appears to be ultimately flawed. Even if Commercial Crew was fully funded tomorrow, the participating private companies would still have to go through the same development and certification process for their spacecraft, and their launch date would still be two years into the future, at the very least. “Engineering is engineering,” said Kelly O. Humphries, News Chief at NASA’s Johnson Space Center, Texas, during an interview for Motherboard earlier last week. “We’re working with commercial companies to make sure everything is done properly so the spacecraft will interact properly with the International Space Station. You’ve got to do things the right way, to make sure things are safe for people.”

According to Dr. William L. Anderson, Associate Professor of Economics at the Frostburg State University, Md., the reason behind NASA’s announcement is just political posturing: “I think the decision, and I guarantee, it didn’t come from NASA, it came from the White House,” said Anderson during an interview for the Voice of Russia. “They want to make it look like they are doing something and so they pick what they would think would be an easy target. Although, let’s face it, it is not going to change anything in Crimea, it is not going to change the situation … I would say, [the ones to benefit are] probably the White House and certain Democrats and probably some Republicans, people who want to talk tough, that we have Americans that are looking at this and say “we have to stand up to aggression.” And is it hypocritical? Yes, but that is where it is coming from. You have people who are running for reelection, you have 1/3 of U.S. Senate, the entire House of Representatives running for reelection this year. So, you are going to have people trying to score political points. I guess they would be the ones to benefit. Certainly the people in NASA, especially the ones who become close to the people in Russian space agency, we are talking about people who are friends, they are not going to benefit from it, they are going to be hurt.”

Ms. Susan Eisenhower, Chairman Emeritus of the Eisenhower Institute and President of the Eisenhower Group, Inc, voiced similar concerns at her testimony last week before the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation Subcommittee on Science and Space, during a hearing titled “From Here to Mars”: “I was concerned to read NASA’s announcement last week that, in light of the Crimean crisis, NASA will suspend ‘the majority of its ongoing engagements’ with Russia, with the exception of continued US-Russian cooperation on the International Space Station …Those who are aggressively pushing for using space as a way to ‘punish Russia’ should be reminded that contact with countries that have [space] technical capabilities, have in the past been a way to enhance transparency …We must be wary of any space policy that provides only short-term symbolic satisfaction, just as we should be cautious of those who might want to exploit this crisis for short-term commercial or political gain. They could ultimately undermine our long-term strategy in space and possibly jeopardize the enormous human and financial investment we have already made.”

Even though Congress is largely to blame for underfunding the Commercial Crew program, thus denying the U.S. the ability to have a domestic launch capability sooner rather than later, the White House and NASA’s current leadership share as much a responsibility for putting the U.S. in such a position of dependency on Russia in the first place. Following his first months in office, President Obama made a sudden and unprecedented change of course in U.S. space policy, by announcing both the retirement of the space shuttle and the cancellation of the Constellation program, which aimed to provide access to low-Earth orbit and send astronauts to the Moon by 2020.

In all fairness, the shuttle’s retirement had already been announced by the previous George W. Bush administration back in 2004, following the tragic Columbia accident that occurred a year earlier. Yet its retirement was a part of Bush’s Vision for Space Exploration, or VSE, that was announced at the same time, which NASA’s Constellation program aimed to implement. Under this plan, the shuttle was to be phased out in 2010, following the completion of the ISS, to be replaced by the Ares I and Ares V launch vehicles for sending the also newly announced Orion crew capsule to destinations in low-Earth orbit and beyond. Even though the VSE was supported by Congress in both the 2005 and 2008 NASA Authorisation Acts, unfortunately it didn’t receive the funding required, causing the program’s schedule to slip. “Congress has its own responsibility to bear in these matters,” said Rep. Chaka Fattah(D-PA2), Ranking Member on the Commerce, Justice, Science, Subcommittee of the House Appropriations Committee, during a hearing held earlier this week concerning NASA’s FY2015 budget request. “It wasn’t the Obama administration, it was the FY2006 CR that underfunded Constellation to the point which it created this problem. This is before Obama was sworn in … But that is the origin of why there was a domino [effect] to the cancellation of Constellation. We need to put this in perspective.”

Although President Obama inherited the decision to retire the space shuttle by the previous administration, he also inherited the rest of the Constellation program as well. The newly appointed President chose to terminate both programs, however, while apparently failing or not caring to properly take into account the U.S. dependency on Russia that would result by this decision for launching American astronauts to the ISS for many years in a row until new replacement vehicles could be developed. Since the retirement of the shuttle was tied to the development of the Constellation program, a cancellation of the latter should prompt a re-thinking of the decision for the former, something that ultimately didn’t happen. The space shuttles were finally decommissioned following the STS-135 flight in July 2011.

That point was also stressed by Rep. Mo Brooks (R-AL) during a debate with NASA’s Administrator Charles Bolden at the recent hearing for the NASA Fiscal Year 2015 Budget Request, held by the House of Representative’s Committee on Science, Space, and Technology. “When the Space Shuttle was mothballed, President Obama was President of the United States. He could have made the decision to have continued to use the Space Shuttle, or he could have made the decision to keep it available in the event of an emergency. He chose not to,” said Brooks.

The resulting dependency on Russia, for which NASA’s Administrator Charles Bolden has always been quick to express his vocal opposition and concern, apparently wasn’t an issue when this decision was taken. “I was the one who recommended to the President that we phase the Shuttle out,” answered Bolden. “I would have recommended we phase it out quicker. We were spending $12 billion over the same period of time that we have spent on SLS and Orion now.”

Even though the shuttle had been deemed too risky and expensive in the aftermath of the Columbia accident, NASA’s choices were rather limited when it came to low-Earth orbit access anyway. It would either keep the shuttle flying after the cancellation of the Constellation program until a cheaper replacement was ready (like the proposed vehicles under the Commercial Crew program), or it would retire it prematurely, thus relying on Russia for transportation services to the ISS. Seen in this light, Bolden’s argument that Congress alone is responsible for having NASA sending millions of dollars to the Russians seems more like an attempt at scoring some political points on behalf of the White House, rather than an honest assessment of the situation.

The Commercial Crew program has been one of the many points of debate between NASA and Congress, with the latter sharing most of the blame for not helping to accelerate the program’s development. NASA and the White House, on the other hand, have been consistently decrying the current lack of ability by the U.S. to launch its own astronauts to low-Earth orbit. They both share the same blame, however, for failing to provide the necessary leadership to prevent this from happening in the first place, despite all the declarations of commitment to the contrary.

You can read Part 2, here.

The author would like to thank AmericaSpace’s Jim Hillhouse and Ben Evans for providing their kind feedback.

The opinions presented in this article belong solely to the author and do not necessarily represent those of AmericaSpace.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

The fault still lies primarily with Congress. If Congress had funded commercial crew as requested, it’s likely that at least one system would be ready to enter service next year. I say likely because you don’t know for certain what sorts of delays the program might have encountered on the technical side.

The key aspect the author overlooks were the mounting delays on Orion and Ares I. It’s unlikely they would have been ready to launch crews to station much before the 2016 time frame. And could have slipped. And developing both of them would have cost much more money.

Cancelling Ares I and going with a commercial crew effort using existing boosters already in use (Atlas V) and in development (Falcon 9) was a reasonable decision. Congress is obsessed with funding SLS and Orion, which is 2/3 of Constellation saved from the junk heap. And it thought there would be no consequences to extending our reliance on Russia. Now they realize how precarious everything is, and last week they were asking Bolden what the contingency plan is. And there’s no contingency plan. NASA can’t afford one.

Congress did not pick the authorized commercial crew funding numbers out of thin air but in conjunction with OMB and the White House in a deal that formed the comprise that was the 2010 NASA Authorization Act.

The White House subsequently didn’t like the numbers it had negotiated with the then Democratic controlled Congress and requested nearly $350 – 550 million more than authorized levels in its subsequent budgets. That Congress did not want to go along and renegotiate its previously agreed upon funding levels for CCP is not its fault, it is solely the fault of the White House.

Commercial Crew Funding Levels (in millions)

Pres Requested, Authorized, Appropriated

FY2011 $812 $312 $312

FY2012 $850 $500 $406

FY2013 $829.7 $500 $525

The White House has known, given the authorized levels in the 2010 NASA Authorization Act, that if it wanted to move faster on CCP, then NASA would have to do a down-select sooner rather than later. Congress has over the last 2 1/2 years told NASA that it was time to move along on commercial crew.

NASA Administrator Bolden’s protestations that NASA hasn’t gotten what it needed for CCP is revisionism, plain and simple. NASA needs to work within the funding limits outlined by law and negotiate better CCP funding numbers in the coming NASA Authorization Act. But the notion that CCP was underfunded by Congress is simply inaccurate.

Not sure how hard and fast those limits were because there have been significant differences in some years on what the Senate has been willing to provide commercial crew and the much more miserly House. My sense is that when you use the word Congress, you are describing what the House’s position is on these matters.

The House seems extremely confused much of the time on the very idea of commercial crew. It seems not to like competition in the program. Instead, it wants a traditional FAR-based, cost-plus approach in which one winner is chosen almost immediately.

I suppose this explanation this comes from those Congressional aides you talk with. Did you check with them and get this answer because the original comment stayed in moderation for quite a while before it was posted.

President Obama also inherited a policy from the Bush administration to end the ISS program after 2015 in order to fund the Constellation program. But President Obama canceled those plans, choosing to continue the ISS program– now into 2024.

That’s $27 billion that could have been used for beyond LEO development or for the next generation of larger and cheaper microgravity space habitats and rotating space habitats that could produce a simulated gravity for interplanetary journeys.

Marcel

Marcel,

I’m going to provide some backup to your point, the source of which can be found at this Link. Anyone claiming that it would cost billions to “restart” the Shuttle program in 2010 are wrong and, unlike the author of the comment below, simply don’t know what they are talking about.

This is from the 2008 NASA Authorization Act. It specifically preserved the option for continuing shuttle beyond 2010 for the incoming Administration–which was of course unknown when the legislation was drafted and even when enacted on October 15, 2008. Subsequent to the election, this provision was very clearly pointed out to the Obama Transition Team for NASA (headed by Lori Garver) and they clearly understood they had the option to continue–and that the Congress would likely support that move, given its history, since 2005, of concern about “The Gap,” especially with respect to the ability to support and sustain ISS. They “punted” that decision to the overall HSF Review Committee (Augustine), who, in the end provided a series of options among which was continuation of Shuttle to 2015, by which time it was expected that Ares 1 would be flying. The FY 2011 Budget Request the following year demonstrated THIS Administration’s DECISION:

Section 611

(d) TERMINATION OR SUSPENSION OF ACTIVITIES THAT WOULD PRECLUDE CONTINUED FLIGHT OF SPACE SHUTTLE PRIOR TO REVIEW BY THE INCOMING 2009 PRESIDENTIAL ADMINISTRATION.—

(1) IN GENERAL.—The Administrator shall terminate or suspend any activity of the Agency that, if continued between the date of enactment of this Act and April 30, 2009, would preclude the continued safe and effective flight of the Space Shuttle after fiscal year 2010 if the President inaugurated on January 20, 2009, were to make a determination to delay the Space Shuttle’s scheduled retirement.

(2) REPORT ON IMPACT OF COMPLIANCE.—Within 90 days after the date of enactment of this Act, the Administrator

shall provide a report to the Congress describing the expected budgetary and programmatic impacts from compliance with paragraph (1). The report shall include—

(A) a summary of the actions taken to ensure the option to continue space shuttle flights beyond the end

of fiscal year 2010 is not precluded before April 30, 2009;

(B) an estimate of additional costs incurred by each specific action identified in the summary provided under

subparagraph (A);

(C) a description of the proposed plan for allocating those costs among anticipated fiscal year 2009 appropriations

or existing budget authority;

(D) a description of any programmatic impacts within the Space Operations Mission Directorate that would result

from reallocations of funds to meet the requirements of paragraph (1);

(E) a description of any additional authority needed to enable compliance with the requirements of paragraph

(1); and

(F) a description of any potential disruption to the timely progress of development milestones in the preparation

of infrastructure or work-force requirements for shuttle follow-on launch systems.

122 STAT. 4798 PUBLIC LAW 110–422—OCT. 15, 2008

Added Note: Since the above provision expired at the end of April 2009, NASA, knowing of the HSF Review, elected to take only non-irreversible termination activities pending the outcome of that review, and pending the Administration’s formal response to that review as part of the FY 2011 Budget Request. Thus, the Bush-initiated termination “decision” could have been reversed as late as the Spring (and actually into the summer) of 2010. As added “insurance” for that option, the 2010 Act included language “protecting” ET-94 to enable the shuttle flow to ramp back up. Senator Hutchison also introduced a bill (S. 3068), the ‘‘Human Space Flight Capability Assurance and Enhancement Act of 2010″, which provided for a recertification process for Shuttle, authorized funding for two flights per year for FY 2010, 2011 and 2012, and required a joint determination by the President and the Congress regarding a decision to terminate the shuttle. Rather than pursuing passage of that bill, it became the starting point on the Republican side of negotiations regarding the content of the 2010 NASA Authorization Act, and the removal of those shuttle provisions became part of the “Compromise” that produced the 2010 Act.

Actually, the NASA Authorization Act of 2008, Title 6, Sec. 601, (a) and (b) preventing any activities by NASA to cease ISS operations in 2015. I have not heard whether the Obama Administration led a charge on Capitol Hill for continuing ISS operations beyond 2015. The primary force behind keeping ISS operating beyond 2015, and who largely crafting the following language, was Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison.

SEC. 601. <> PLAN TO SUPPORT OPERATION AND

UTILIZATION OF THE ISS BEYOND FISCAL YEAR 2015.

(a) In General.–The Administrator shall take all necessary steps to> general.–Not later than 9 months

ensure that the International Space Station remains a

viable and productive facility capable of potential United States

utilization through at least 2020 and shall take no steps that would

preclude its continued operation and utilization by the United States

after 2015.

(b) Plan To Support Operations and Utilization of the International

Space Station Beyond Fiscal Year 2015.–

(1) In <

after the date of enactment of this Act, the Administrator shall

submit to the Committee on Science and Technology of the House

of Representatives and the Committee on Commerce, Science, and

Transportation of the Senate a plan to support the operations

and utilization of the International Space Station beyond fiscal

year 2015 for a period of not less than 5 years. The plan shall

be an update and expansion of the operation plan of the

International Space Station National Laboratory submitted to

Congress in May 2007 under section 507 of the National

Aeronautics and Space Administration Authorization Act of 2005

(42 U.S.C. 16767).

(2) Content.–

(A) Requirements to support operation and

utilization of the iss beyond fiscal year 2015.–As part

of the plan required in paragraph (1), the Administrator

shall provide each of the following:

(i) A list of critical hardware necessary to

support International Space Station operations

through the year 2020.

(ii) Specific known or anticipated maintenance

actions that would need to be performed to support

International Space Station operations and

research through the year 2020.

(iii) Annual upmass and downmass requirements,

including potential vehicles that will deliver

such upmass and downmass, to support the

International Space Station after the retirement

of the Space Shuttle and through the year 2020.

Running off Von Braun was the first sign NASA had lost its way. It’s been lost every since. Letting Skylab burn up…yeah that’s smart? NASA is white collar welfare. It has been for 40 years. It’s really a national catastrophe as engineers are the engine of our economy and they shouldn’t be wasted on NASA. Getting into the space truck business…silliness. NASA is only valuable if it’s doing research that’s of value to the economy or adding to our body of knowledge. Space trucks are BS. That should be performed by industry as Musk is demonstrating.

Good article. From the title I thought it would be too critical but it was fair and balanced.

Personally, I wouldn’t care if they cancelled the ISS today as long as they spent the savings on building super-heavy rockets. Don’t get me wrong, I love the ISS, but space stations are pointless. Polyakov proved people can spend over a year in space and physically recover just fine. Beyond that, any manned LEO research pales in value to robotic exploration and the colonization of Mars. Mars is a six-month journey. We don’t need any more research and we don’t need a giant modular cruiser. Stuff four people into Zubrin’s camper-van, blast them off to the red planet and be done with it. Astronauts average a 1/65 chance that they’ll die in an fireball but we’re ringing our hands over bone-loss and radiation. If we can send thousands of americans to their death in Iraq then it’s absurd to say that we’re above trading lives for things we believe in and you can be damn sure that an astronaut strapped to a million tons of explosives isn’t anxious about his risk of cancer…

Hi Joe –

von Braun resigned from NASA immediately after Nixon forced Thiokol solid boosters on Fletcher.

(By the way, I have this on tapes, first hand interviews.)

Moving on to other matters of historical fact, as far as Obama shutting down the shuttle, Griffin did that under Bush Jr.

I always thought that the reason we paid Russia above market rates to launch our astronauts into space was to provide them with cash for their space program…and to keep their areospace engineers from going to work in Iran or North Korea …or SpaceX…It doesn’t seem that long ago that everyone was worried that Russia would disconnect their modules from the ISS…..If the US stops paying them, I thinking that is what they would do….The country is run like the Mob…No?

Professor Anderson from Frostburg State–that glittering citadel of foreign policy expertise–does not know what he is talking about. There was no order from the White House to do anything, other than review all Russian cooperation activities, across the federal government. Two individuals at NASA — one a senior civil servant, and one a junior political appointee — decided that NASA should cut off cooperation. They drafted the memo and Bolden signed off. Period. It wasn’t external… it was internal NASA brilliance.

According to Marcia S. Smith, editor of the Space Policy Online website, that’s not the case. Quoting from Smith’s recent Q&A article regarding the issue:

Why did NASA do this?

NASA didn’t “do this.” Administration officials tell us that NASA is following a classified directive from the White House National Security Council that applies to all government agencies. The directive is not aimed at NASA specifically. NASA is part of the Executive Branch of government and must follow White House directives.

Everyone in NASA and the White House and Congress knows they don’t have a problem. They all know SpaceX can put crash couches into a Dragon, send it up empty and bring home every non-Russian on the ISS with virtually no risk. All the bro-hahah is about LAUNCHING with crewed vehicles. Dragon has demonstrated clearly that it’s re-entry, descent, splash-down, tracking and recovery systems work just fine.

NASA also knows that it could, if it wished, waive the testing and certification of the launch-abort system for Dragon, and SpaceX could put crash couches into a Dragon and send 1 to 7 astronauts to the ISS with about the same risk profile as every Shuttle used to build it.

Sending crew with no piloting responsibilities to the ISS is immediately doable and everyone concerned knows it. That’s why there’s no panic and no real concern about being reliant on Soyuz.

Same launch risk profile as Shuttle? So this launched crewed Dragon will have a crew-in-the-loop GNC, rendezvous, and proxops capability as Shuttle? Will it even have an ECLSS? No. I would give a body part to be in the room when Gerst is told to ready Dragon for crewed ops now. Fireworks wouldn’t even begin to describe the outcome.

Yes, same risk profile. No ability to abort on the pad. No ability to abort during boost phase. (Well, we all know there WILL be an ability – it just won’t have been thoroughly tested, but I digress). You strapped into a Shuttle mission, you knew that you died if you didn’t get to SRB separation.

I guarantee you that Musk is ready to send a crew to ISS if necessary. He knows, his engineers know, NASA knows, and the Russians know that “pilots” are unnecessary. Dragon, Cygnus, ATV, HTV and Progress all do autonomous rendezvous. The whole bit about guys in flight suits with joysticks and reticles heroically “flying” around in orbit is space theater. Yeah, for Dragon someone needs to be at the controls of the arm to capture the capsule and dock it. Maybe. I suspect much of that is space theater too. Is a body looking at a video display and running the robot arm on the ISS really unreplacable with a body sitting in Mission Control watching the same video display with the same controls?

The point of my comment is not that this is desirable or likely, only that it is FEASIBLE. The feasibility is what gives everyone in the system confidence that they’re not going to be held hostage by the Russians.

Doing a crewed Dragon mission IN AN EMERGENCY, which is what we’re talking about, involves nothing more than installing crash couches and some kind of life support. In an emergency, the life support system could be closed suits and a closed breathing system.