The location at which the feet of Yuri Alexeyevich Gagarin—the first human ever to break the bonds of Earth and enter space—made contact again with terra firma took place in a field some 15 miles southwest of the town of Engels, in the Saratov region, near Smelovka. Today, the site is marked by a 35-foot-tall (10-meter) obelisk and plaque, inscribed with the legend “Y.A. Gagarin Landed Here.” The formal marker was placed there on 14 April 1961, two days after Gagarin’s historic flight. However, the historic nature of the event had already led someone to erect a small commemorative signpost on the spot, instructing potential trespassers not to remove it and announcing the time of his landing as 10:55 a.m. Moscow Time. Less than two hours had elapsed since Gagarin’s launch … around the same time it would take you or me to watch an average-length Hollywood blockbuster.

Tractor driver Yakov Lysenko heard, but could not see, the ejection sequence as a loud “crack” in the sky. Seconds later, he saw the Vostok capsule descending under its own automatically deployed parachute and immediately returned to Smelovka to raise the alarm. A hastily assembled search party was greeted by what Lysenko would later describe as a “very lively and happy” Gagarin, who identified himself as “the first space man in the world.” Farmer Anna Takhtarova also recalled the strange sight of the orange-suited cosmonaut telling them not to be afraid and asking for a telephone to call Moscow. Shortly thereafter, the Soviet military, under General Andrei Stuchenko, arrived in force to take over the recovery effort. Gagarin had been promoted to the rank of major during his flight and was greeted as such by one of the local officers, Major Gasiev. “It was a complete invasion force,” Yakov Lysenko said later of the military’s arrival. “They didn’t allow us to get too close. They’re very strange people.” It was understandable, at least from Stuchenko’s perspective. He had already been told in no uncertain terms by an anonymous Kremlin official the previous day that on his head lay the responsibility to safely recover Gagarin. Stuchenko obviously wanted to leave nothing to chance.

The Vostok capsule hit the ground a couple of miles from the cosmonaut himself, since his high-altitude ejection had caused them to drift apart. For years, the spacecraft’s landing site was officially one and the same with Gagarin’s own, to avoid FAI suspicions that both had not touched down together. However, the Vostok site is known with certainty, thanks to a group of children who happened to be playing in a meadow near the banks of a tributary to the Volga River. They saw the capsule land. Schoolgirls Tamara Kuchalayeva and Tatiana Makaricheva described the dent it left in the soft earth and related how the boys clambered inside and began handing out and trying the tubes of space food. “Some of us were lucky and got chocolate,” Makaricheva recalled of the unusual mid-morning snacks. “The others got mashed potatoes. I remember tasting some and spitting it out.” Kuchalayeva agreed that she would not eat it again. Gagarin’s 108-minute adventure, it seemed, made him a hero not only for being the first to survive space, but also for being the first to survive the tastelessness of space food.

Twenty minutes after the R-7 blasted off, cosmonaut commander Nikolai Kamanin boarded an An-12 aircraft, bound for the industrial city of Kuibishev, today’s Samara. With him were Gherman Titov, Mark Gallai, and a substantial delegation from Baikonur. Whilst airborne, they learned of Gagarin’s landing in Saratov and toasted his success with cognac. The cosmonaut, meanwhile, had already spoken with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev by telephone from Engels, before heading on to Kuibishev. On the outskirts of the city, in a special dacha on the banks of the Volga, Gagarin was given a medical examination and a day’s rest before his journey to Moscow. The mission was over. Shortly, his new life as an international celebrity would begin.

But not yet.

On 13 April, whilst still secluded in the Kuibishev dacha, he underwent his official two-and-a-half-hour interview by the Vostok State Commission—the only opportunity for “the truth” about the mission to be revealed, behind closed doors, to high-ranking officials. Although he undoubtedly described the problem with the instrument section, it remains unclear as to why this was not properly resolved in time for the next flight, Vostok 2, other than the possibility that changes were implemented, but failed to work. Meanwhile, efforts to secure the World Aviation Altitude Record had already led sports official Ivan Borisenko to hurriedly get the First Cosmonaut’s signature on FAI documents within hours of landing. In his fictitious account of the proceedings, published in 1978, Borisenko would recall “dashing up to the descent module, next to which stood a smiling Gagarin.” The reality that capsule and cosmonaut landed a couple of miles apart was kept closely guarded.

After his day on the Volga, during which time he also played billiards with Titov and described his experiences, Gagarin flew to Moscow on the morning of 14 April aboard an Ilyushin-18. He had already rehearsed the half-hour speech that he would deliver to Khrushchev, but could hardly have anticipated the sheer outpouring of adoration for him. On the outskirts of the capital, a squadron of seven MiG fighters intercepted his aircraft and escorted him down Lenin Prospekt, Red Square, and along Gorky Street to Vnukovo Airport, where the Il-18 touched down just a few hundred feet from Khrushchev’s flower-decked reception stand. The premier congratulated Gagarin, announcing that “you have made yourself immortal because you are the first man to penetrate space.” Following the party line, the First Cosmonaut responded by challenging the “other countries” to try to catch up with superior Soviet technology.

However, partly due to sour grapes, but mainly because of the intense mistrust that the Russians had themselves created through their ridiculous secrecy, some observers in those “other countries” were already doubting that the mission had happened at all or—at the very least—that it had not occurred precisely as reported. The Soviet campaign of misinformation became evident when their sports officials filled in the FAI paperwork to register Gagarin’s flight on 30 May 1961. The name and co-ordinates of the launch site, they wrote, were “Baikonur” at “47°22′00″N, 65°29′00″E,” whereas in reality the site was close to the tiny Tyuratam rail junction at 45°55′12.72″N, 63°20′32.32″E, a considerable distance to the southwest. Indeed, speculation abounded as late as July 1961 over conflicting reports, obscure photographs, and a lack of reliable eyewitnesses. Other suspicions lingered over whether Gagarin landed in his capsule or by parachute. On 17 April, just five days after the mission, a correspondent for the London Times wrote that “no details have been given about the method of landing” and revealed that, when questioned at a press conference, Gagarin had “skated over the question.”

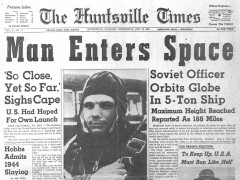

Nonetheless, within hours of the flight, NASA Administrator Jim Webb appeared on American television to congratulate the Soviets and express his disappointment, but also to offer reassurance that Project Mercury—the United States’ own man-in-space effort—would not be stampeded into a premature speeding-up of its schedule. His remarks did little to dampen the fury of the House Space Committee, which verbally roasted both Webb and his deputy, Hugh Dryden, on 13 April. It made no difference; the Soviets had won the first lap of the space race, and John Kennedy, still only months into his presidency, had to respond with something spectacular. Faced with persistent questions from Congress as to why the United States should remain in second place to Russia in space, together with a perceived “gap” in missile-building technology, Kennedy knew that Project Mercury’s first manned flight would not even match, let alone surpass, Vostok’s achievement. Indeed, it was unlikely that a single-orbit piloted mission could be attempted before the end of 1961, so temperamental was the new Atlas launch vehicle needed to achieve such a feat. By that time, the Soviets could well have pushed their lead even further.

A goal on a longer-term basis, with an above-average chance of success, was crucial for America’s young president. On 14 April, Kennedy called an informal brainstorming session with several aides to discuss suitable space goals. Landing a man on the Moon emerged as the best option to draw the Soviets into a race which the United States could conceivably win. Not only would it convey a message to the world of American technological prowess, but it would clearly beat Russia. A few days later, however, circumstances on a Caribbean island just southeast of Florida made Kennedy’s need for something—anything—to bolster his administration even more urgent.

That “something” was announced by the young president before a joint session of Congress, on 25 May 1961: the goal to land a U.S. astronaut on the surface of the Moon, and bring him safely back to Earth, before the end of the decade. It was an audacious goal, particularly as the United States’ first manned space mission had not even achieved orbit, carrying Alan Shepard on a 15-minute suborbital flight on 5 May. Kennedy’s motivations for announcing the lunar goal have been debated endlessly over the years, and it is certain that his decision was governed in part, if not wholly, by politics and the need to stress U.S. technological prowess and ideological muscle, but whatever led him to target his nation’s resources toward a Moon landing owes everything to the flight of Yuri Gagarin. For without Gagarin’s incredible bravery and gusto on that April day in 1961, it is certain that history would have played out differently. Maybe a human being would have set foot on the Moon. But almost without doubt, it would not have happened as soon as it did … and that draws us to respect Gagarin for two reasons: firstly, for being the first of us to venture into space, and secondly, for setting our feet on the path to even grander goals.

This is part of a series of history articles, which will appear each weekend, barring any major news stories. Next week’s article will focus on the 20th anniversary of STS-59, a shuttle mission from April 1994 which mapped huge expanses of the Home Planet with powerful radar.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Ben: Well done! Bravo!

Indeed Ben, and also, thank you very much!

Ottima ricostruzione!

Congrats! Absolutely a super and gripping story of Gagarin’s historic flight.

Suggest you convert it into a book.