“A damn fine month,” actor Morgan Freeman’s character Ellis “Red” Redding remarked in the movie Shawshank Redemption and, indeed, for America’s space program, the month of May—newly dawned—has long been a historic one for off-the-planet U.S. achievements. Sixty years ago today, on 5 May 1961, the nation saw Alan Shepard become the first American to voyage into space; a short suborbital “hop”, in which he ascended 116.5 miles (187.5 km) in the tiny Freedom 7 capsule, rising from Cape Canaveral and splashing down 15 minutes later in the Atlantic Ocean.

Other missions launched this month in history include the most recent manned flight on an Atlas booster, the Apollo 10 dress rehearsal for Neil Armstrong’s historic lunar landing, the salvation of Skylab, the first International Space Station (ISS) docking mission, the maiden and swansong voyages of shuttle Endeavour and the last Hubble Space Telescope (HST) servicing call.

And in May of last year, the Demo-2 mission of Dragon Endeavour—carrying NASA astronauts Doug Hurley and Bob Behnken—got underway, kicking off the first U.S. human space mission, aboard a U.S. spacecraft, atop a U.S. rocket, and from U.S. soil, since the twilight of the shuttle era.

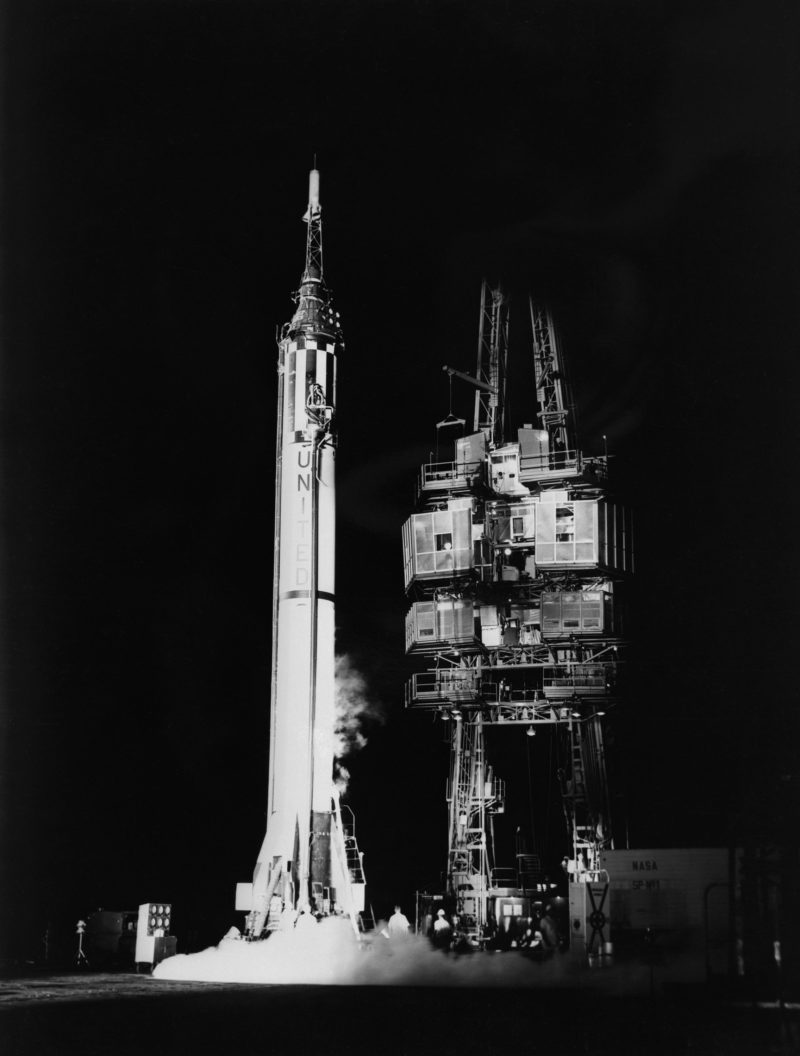

Shepard’s launch six decades ago came on the heels of disappointment, for just three weeks earlier on 12 April 1961 Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first man to enter space and orbit the Earth. It would be several months before the United States had a similar capability with its Atlas rocket, but in the meantime Shepard would fly a converted Redstone ballistic missile into suborbital space.

Early on 5 May 1961, he boarded the bell-shaped Freedom 7 capsule on Pad 5 at the Cape, ready for a voyage that promised to end with his death or with eternal fame. Shepard’s first action inside the tiny capsule was to chuckle at a picture of a pin-up girl and a placard—“No Handball Playing In This Area”, it read—put there by his backup, fellow astronaut John Glenn.

Liftoff was scheduled for 7 a.m. EST, but banks of cloud over Florida’s southeastern seaboard quickly produced a raft of delays. A power inverter to the Redstone booster also exhibited trouble and needed replacement. Then a computer glitch at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) in Greenbelt, Md., responsible for processing mission data, hiccuped. By this time, Shepard had been lying on his back, fully suited, in the capsule for other three hours. “Man, I gotta pee,” he grumbled to Capcom Gordon Cooper in the nearby control blockhouse. “Check and see if I can get out quickly and relieve myself.”

Unfortunately, with only a 15-minute flight planned, it had not been expected that he would ever be aboard Freedom 7 for long enough to require a toilet break. Cooper passed the request up the chain of command, where it eventually reached the ears of Wernher von Braun, head of NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in Huntsville, Ala. His reply was emphatic. In his thick German accent, von Braun snapped: “No! Ze astronaut shall stay in ze nose-cone!” Exasperated, Shepard told Cooper he would have to urinate in his suit if the hold went on for much longer. At length, power was switched off temporarily and a drawn-out “Ahhhh” came from the astronaut.

In his post-flight debriefing, recorded on hour later on the USS Lake Champlain, Shepard noted that urinating in his own suit may have affected several of his sensors, but it certainly improved his comfort. Also, the urine was quickly absorbed by his long cotton underwear and rapidly evaporated in the 100-percent pure oxygen atmosphere of Freedom 7.

Rescheduled for launch at 9 a.m., the clock was halted yet again by rising pressures in the Redstone’s liquid oxygen tank and mutterings of whether to scrub for the day or bleed off the pressure remotely. Shepard had had enough. “I’m cooler than you are,” he barked. “Why don’t you fix your little problem and light this candle?” His words appeared to have the desired impact and shortly after 9:30 a.m. the countdown resumed and America’s television networks began their live coverage.

Data from his biomedical sensors revealed a quickened pulse-rate from 80 to 126 beats per minute in the final 30 seconds of the countdown. His hand tightened around Freedom 7’s abort handle and, in his mind, he repeated an early incarnation of the Astronaut’s Prayer: God help you if you screw up. At 9:34 a.m., with an estimated audience of 45 million Americans watching or listening in person, on television or radio, the Redstone took flight. “Liftoff, and the clock is started!” radioed Shepard.

Ascent was, by his own admission, smoother than anticipated and he did not need to amplify the volume control to receive transmissions from the ground. As the Redstone climbed higher through the rarefied atmosphere, Shepard’s calls crackled over the radiowaves, communicating fuel readings, oxygen readings, G-meter readings and systems readings.

But in spite of a relatively smooth liftoff, things took a bumpier turn when the rocket reached the region of maximum dynamic pressure. Freedom 7 shuddered violently and Shepard’s helmeted head, according to his biographer Neal Thompson, began “jackhammering so hard against the headrest that he could no longer see the dials and gauges clearly enough to read the data.” Thankfully, the vibrations calmed just as quickly.

Two and a half minutes into flight, the Redstone’s Rocketdyne-built A-7 engine shut down as intended and the escape tower was jettisoned. (It would appear that Shepard also pulled the manual “JETT TOWER” override, fearful that the automatic system might fail.)

Traveling in excess of 5,000 mph (8,000 km/h), three times faster than any American in history, the astronaut spent a few minutes testing his controls, tilting the capsule through pitch, yaw and roll maneuvers, the spurting hydrogen peroxide thrusters often drowned out by the crackling voice on the radio. Weightlessness, too, came as a pleasant sensation, as his body rose gently from his seat and flecks of dust and a steel washer drifted past his face.

Approaching an apogee of 116.5 miles (187.5 km), he peered through Freedom 7’s periscope to catch a glimpse of Earth. Unfortunately, during the morning’s delays, in order to prevent sunlight from blinding him, he had flipped a switch to cover the lens with a gray filter and had forgotten to remove it. His view of the Home Planet was thus gray-tinged. Shepard tried to reach across the cabin to flick off the filter, but as his wrist inadvertently brushed the abort handle he thought it best to leave well alone.

“What a beautiful view,” he breathed as his limited perspective took in Lake Okeechobee, Andros Island, Bimini and the cloud-cloaked Bahamas. At length, the capsule’s retrorockets fired at 9:40 a.m. to begin the descent.

Shepard would later recall that re-entry stresses which peaked at 11 G were physically demanding as Freedom 7 slowed from 5,000 mph (8,000 km/h) to under 500 mph (800 km/h) in less than 30 seconds. The astronaut managed only a few guttural grunts over the radio, but temperatures inside the capsule remained comfortable, akin to a closed van on a warm summer’s day.

Four miles (6.4 km) above the Atlantic Ocean, the drogue parachute was deployed out of Freedom 7’s nose, the antenna capsule was discarded and a huge main canopy, 63 feet (19 meters) wide, unfurled as planned. In Shepard’s words, the deployment of the main parachute afforded “a reassuring kick in the butt”.

Splashdown at 9:49 a.m. came in a stately fashion, with the capsule impacting the Atlantic Ocean some 300 miles (480 km) east of Cape Canaveral and within sight of the recovery ship, USS Lake Champlain. America’s first manned space mission had lasted 15 minutes and 28 seconds. Freedom 7 listed over to its side, then righted itself, and within minutes the first of five Marine Air Group 26 helicopters from the recovery ship were hovering overhead to snare the capsule with hook and line. Shepard popped open the hatch, grabbed the padded harness lowered by Wayne Koons and George Cox from their helicopter, looped it over his head and under his arm, and was winched to safety.

Twelve hundred sailors aboard the Lake Champlain applauded, as did many at home. Shepard’s mission was a much-needed shot in the arm for the United States at a time when the nation’s scientific and technological prowess was being held in check by the Soviets. Three weeks later, President John F. Kennedy committed America to landing a man on the Moon before the decade’s end.

The importance of the month of May in U.S. human space endeavors did not stop there. In May 1962, Scott Carpenter flew a five-hour mission aboard the Aurora 7 capsule for a voyage which—despite a multitude of problems which might have cost the astronaut his life—conducted a wide range of valuable scientific and technical experiments. And a year after that, in May 1963, Gordon Cooper flew the longest mission of Project Mercury, nurturing his Faith 7 capsule through 34 hours and 22 Earth orbits.

In May 1969, Apollo 10 astronauts Tom Stafford, John Young and Gene Cernan became the second crew of humans to journey to the Moon, performing a full dress rehearsal in lunar orbit in readiness for the historic first landing of men on another world. Four years later, America’s first space station, Skylab, rose to orbit and the month of May 1973 saw it run the gamut from potential failure to spectacular salvation in only a few weeks, all thanks to a quite remarkable and heroic, around-the-clock effort by astronauts and ground teams.

Since then, many other astronauts launched or landed in May throughout the Space Shuttle era. In 1989, the STS-30 crew of Atlantis successfully deployed the first planetary space probe—Magellan, bound for a lengthy voyage to radar-map Venus—ever to be launched aboard the reusable spacecraft. In May 1992 and May 2011, shuttle Endeavour flew her first and last missions, both involving four sessions of Extravehicular Activity (EVA).

On STS-49, Endeavour served as the stage for the first (and so far only) three-person spacewalk, to retrieve and affix a new booster onto the ailing Intelsat-603 communications satellite, whilst on STS-134 she installed the final major piece of U.S.-built hardware, the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (AMS), onto the now-complete space station.

In May 1996, another Endeavour crew conducted the greatest number of rendezvous (four) with different space vehicles ever accomplished by the shuttle at that time. A shuttle docking with Russia’s Mir space station followed in May 1997 and two years later shuttle Discovery performed the first docking with the fledgling ISS, bringing a multi-national crew from America, Russia and Canada to the international outpost.

Another ISS docking flight took place in May 2000 and on the first day of May in 2001 Endeavour returned smoothly to Earth having delivered the station’s 57.7-foot-long (17.6-meter) Canadarm2 robotic arm. More recently, on the last day of May in 2008 a Discovery crew rose from Earth to transport Japan’s Kibo lab to the station and in May 2009 the STS-125 astronauts visited and serviced Hubble for the fifth and final time.

Of course, we should not forget the missions which might—but for quirks of fate, circumstance or tragedy—also have launched this month in history. Deke Slayton might have flown in Scott Carpenter’s place on the May 1962 flight, had a heart condition not grounded him from spaceflying for more than a decade.

In May 1966, astronauts Elliot See and Charlie Bassett might have flown Gemini IX on a complex three-day mission of rendezvous, docking and spacewalking, had not their lives been tragically snuffed-out in an aircraft accident earlier that year. And in May 1986, two shuttle missions might have flown within a week of one another to deliver the Jupiter-bound Galileo probe and the Ulysses solar orbiter on their respective missions of exploration and discovery.

Since 2017, America has observed each 5 May as “National Astronaut Day” in honor of Shepard’s flight and the spacefarers who followed in his footsteps. And on the last Friday of January—around the time of the Apollo 1, Challenger and Columbia anniversaries—”Astronauts Day” requests Americans to light a candle in their window and dedicate themselves to a personal goal. As Shepard himself said, all those years ago, days like today serve as an inspiration to “fix our little problems” and “light our own candles”.

Yes, May will long be remembered as a significant month in the annals of American spaceflight achievements.