Fifty-five years ago, in the early hours of 5 May 1961, America prepared to launch its first man into space. Navy Cmdr. Alan Shepard would fly a suborbital flight—rising from Pad 5 at Cape Canaveral in the Mercury capsule he had named “Freedom 7” and splashing down, just 15 minutes later, in the Atlantic Ocean, about 100 miles (160 km) north of the Bahamas—and the entire nation would be holding its breath. Three weeks earlier, the Soviet Union had sent Yuri Gagarin on an Earth-orbital mission and, although the United States was several months away from repeating that feat, Shepard’s flight would alleviate much pressure on the young administration of President John F. Kennedy.

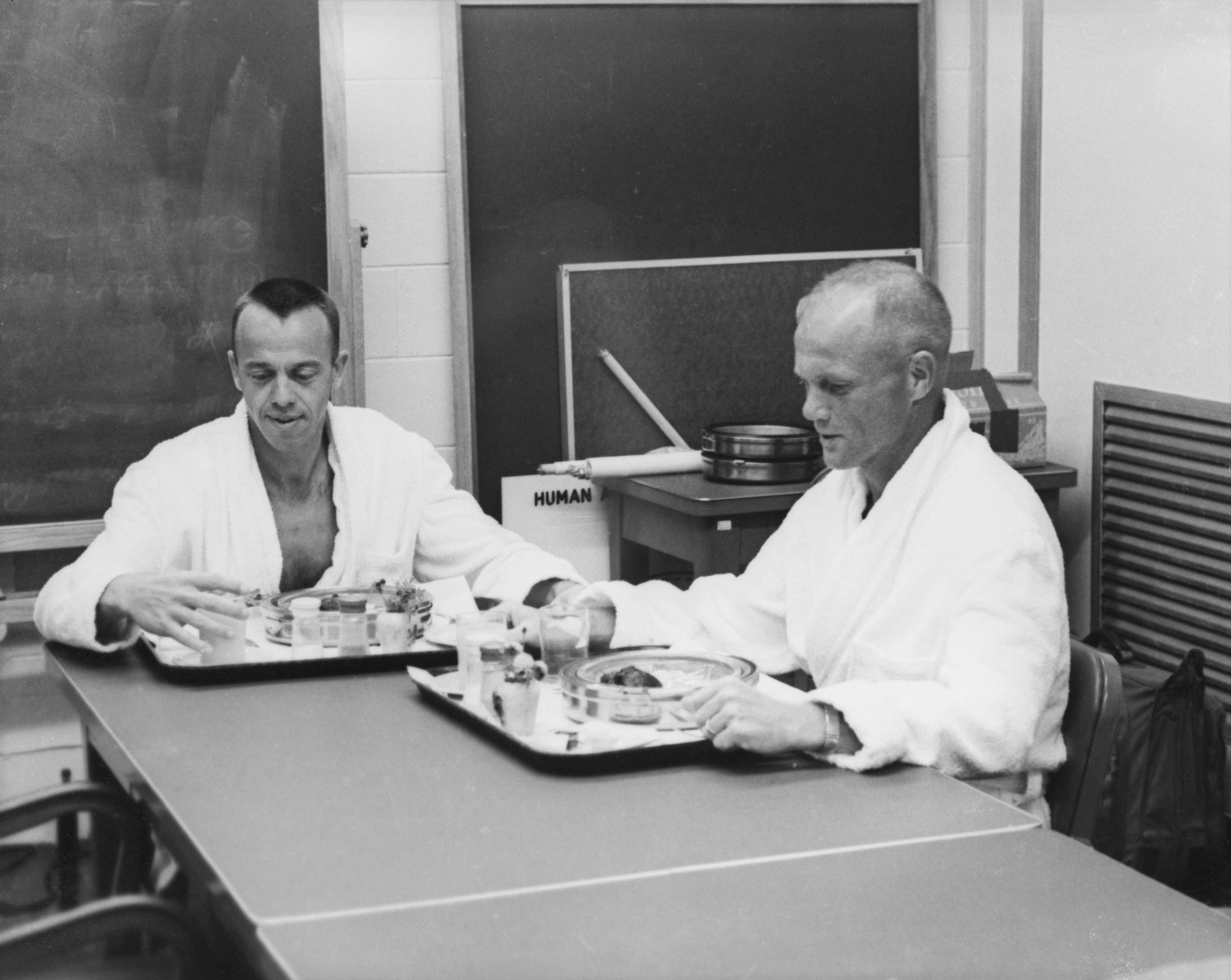

At 1:30 a.m. EDT on the 5th, Shepard and his backup, fellow astronaut John Glenn, met at breakfast in the Cape Canaveral crew quarters, Hangar S. Both were clad in bathrobes. They subsequently parted to dress. Glenn headed out to Pad 5 to check Freedom 7—a bell-shaped capsule, mounted atop a converted Army Redstone missile—whilst Shepard underwent his pre-flight examination, performed by Air Force physician Bill Douglas. Four electrocardiograph pads were attached to his chest, a respirometer to his neck, and a rectal thermometer to gauge deep body temperatures. Next came a set of long underwear, complete with spongy “pads” to help air circulation. Finally, he squeezed into his silver space suit, securing zips and connectors and checking his air-conditioning unit. The latter was essential. By the time he was ready, Time magazine later reported, he was sweating profusely and breathing hard.

A few minutes before four in the morning, fellow astronaut Virgil “Gus” Grissom accompanied Shepard in the transport van to a floodlit Pad 5, where technician Joe Schmitt fitted the gloves and another astronaut, Gordo Cooper, briefed him on the countdown status. Meanwhile, at the top of the gantry, inside the cramped Freedom 7 capsule, John Glenn had spent almost two hours checking the readiness of each switch and instrument. At 5:15 a.m., Shepard ascended the elevator to reach a green-walled room at the 65-foot (20-meter) level (nicknamed “The Greenhouse”), which surrounded the capsule’s hatch. After much huffing and puffing, the astronaut was inserted into his specially contoured couch.

His first action was to chuckle aloud, for Glenn had put a girl pin-up and a placard, which read No Handball Playing in This Area. It was very unlike Glenn, who was normally considered a straight-arrow and not a prankster. He quickly pulled it down. Years later, Shepard’s biographer, Neal Thompson, wrote that Glenn probably had second thoughts and did not want to risk having Freedom 7’s automatic cameras record his joke for dubious posterity.

Joe Schmitt, who suited and booted astronauts for more than two decades, remembered securing Shepard with straps across his shoulders, chest, lap, knees, and even toes. Finally, Glenn reached in, shook his gloved hand, and wished him luck. The hatch closed at 6:10 a.m. and, by his own admission, Shepard’s heart rate quickened. Launch was scheduled for a little after 7 a.m., but this was soon delayed, as banks of clouds rolled over Florida’s south-eastern seaboard. Then, one of the power invertors to Freedom 7’s Redstone booster exhibited trouble. The countdown clock was recycled to T-35 minutes and, after an 86-minute wait, commenced counting again, once the invertor had been replaced. Next came an error with one of the computers at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) in Greenbelt, Md., which was responsible for processing the mission data. By the time this problem had been overcome, Shepard had been lying on his back for over three hours.

Then a more “personal” problem arose.

Not only was it uncomfortable to be lying inside the cramped capsule, but combined with the orange juice and coffee from breakfast it required him to urinate.

“Man, I gotta pee,” he finally radioed to Cooper, stationed in the nearby control blockhouse. “Check and see if I can get out quickly and relieve myself.”

With only a 15-minute flight scheduled, it had not been anticipated that Shepard would be inside Freedom 7 for long enough to feel “the urge.” Still, Cooper passed the request up the chain of command, to Wernher von Braun, the head of NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in Huntsville, Ala. The response was immediate and emphatic. In his thick German accent, von Braun snapped: “No! Ze astronaut shall stay in ze nosecone.” Exasperated—and in an exchange later removed from the official transcript—Shepard warned that he would urinate in his suit if he could not get outside. Managers worried if the urine might short-circuit the medical wiring and electrical thermometers. Finally, Cooper confirmed that the power had been temporarily switched off and, shortly thereafter, a drawn-out “Ahhhhhh” emerged from the astronaut in the capsule. “I’m a wetback now,” Shepard added, as the warm fluid pooled in the small of his back.

In his post-flight debriefing, recorded an hour later aboard the USS Lake Champlain, Shepard acquiesced that his suit inlet temperature changed and may have affected one of his chest sensors, but his comfort was much improved. The urine was absorbed by his long cotton underwear and quickly evaporated in the 100-percent pure oxygen atmosphere of the cabin. Thankfully, the astronaut received no electric shocks and NASA, wrote Neal Thompson, was spared the humiliation of having to report that America’s first space traveler had been electrocuted by his own piss!

The clock was now marching rapidly toward 9 a.m. Two minutes remained on the countdown. Then, another halt was called. Pressures inside the Redstone’s liquid oxygen tank had climbed unacceptably high. NASA had two options. It could either reset the pressure valves—which would necessitate a launch scrub—or bleed off some of the pressure by remote control. An irritable Shepard, after almost four hours on his back and now lying in dried-up urine, obviously preferred the second option. “I’m cooler than you are!” he barked. “Why don’t you fix your little problem and light this candle?” Those final three words have since gained immortality and truly epitomize the “right stuff” from which Shepard was cut. Finally, a little after 9:30 a.m., the clock resumed and the television networks commenced their live coverage. By now, Cooper had been replaced by astronaut Deke Slayton, whose voice would crackle to and from Freedom 7 during the flight.

Thirty seconds to go. An umbilical cable, supplying electricity, communications, and liquid oxygen, automatically separated from the Redstone, as planned.

Shepard’s pulse quickened from 80 to 126 beats per minute. His hand tightened on the capsule’s abort handle and in his mind he repeated, over and over, an early incarnation of “The Astronaut’s Prayer”: God help you if you screw up. He had been inside Freedom 7 for over four hours and the delays alone had cost three and a half hours—long enough to have flown his mission, 14 times over—but now it seemed that all was ready. The jolt of liftoff was not what he had expected. Rather than a harsh acceleration, he experienced something “extremely smooth … a subtle, gentle, gradual rise off the ground.”

At 9:34 a.m., with 45 million Americans watching or listening in person, on TV, on the radio, or over loudspeakers, the Redstone roared aloft, prompting Shepard to activate the on-board timer and radio: “Liftoff … and the clock is started!” The nation could breathe an enormous, collective sigh of relief as their first astronaut speared for the heavens. Yet, as evidenced by a handful of disaster statements, prepared in advance by NASA’s public affairs officer, John “Shorty” Powers, the mission could not be termed a success until Shepard was home, safe, and aboard the recovery ship, USS Lake Champlain. The 15 minutes and 28 seconds between launch and splashdown would prove heart-stopping.

The final part of this article will appear tomorrow.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

I was in 3rd grade in public school, and our principal had the flight piped from the radio through out the school on the intercom. Our teacher was following along on the blackboard the parts of the launch, to discuss later. This was what sealed the deal for me for being a Space and NASA geek.