After almost 188 dramatic days in orbit, Expedition 39 has concluded in spectacular fashion with the safe landing in Kazakhstan of Soyuz TMA-11M and its crew of Russian cosmonaut Mikhail Tyurin, U.S. astronaut Rick Mastracchio, and Japan’s Koichi Wakata. The three men undocked from the Earth-facing (or “nadir”) port of the International Space Station’s (ISS) Rassvet module and landed at 9:58 p.m. EDT Tuesday (7:58 a.m. local Kazakh time Wednesday), near the city of Dzhezkazgan. Touching terra firma for the first time in 187 days, 21 hours and 43 minutes, Tyurin, Mastracchio, and Wakata brought the curtain down on an exciting expedition which saw three contingency U.S. EVAs to restore critical capabilities, featured the arrivals of Progress, Cygnus, and Dragon cargo ships, and marked the first time a Japanese citizen has ever commanded a space mission. However, the landing came amid great trouble on Earth, as Russia’s Deputy Prime Minister Dmitri Rogozin announced that the Kremlin would not support continued ISS operations beyond 2020. This alarming decision, of which NASA apparently had no prior warning, threatens to destroy the hopes of the international partners to keep the station operating beyond 2024.

It was always clear that the steadily deteriorating situation in Ukraine and Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea in March 2014 had caused the deepest rift in East-West relations since the end of the Cold War. Last November, the actions of pro-Moscow Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych to distance himself from closer ties with the European Union (EU) provoked widespread protests, known as “Euromaidan” (“Eurosquare”) in the west of the country. With large swathes of eastern Ukraine remaining strongly pro-Russia in their stance, violence broke out in January 2014 and the parliament found in February that Yanukovych was no longer able to exercise his duties and exercised their constitutional powers to set an election for 25 May to choose his replacement. Matters moved quickly, however, when the ousted Yanukovych sought Russian military and President Vladimir Putin’s troops invaded and annexed Crimea, triggering enormous international condemnation. More recently, on 11 May, the eastern industrial centers of Donetsk and Lugansk held independence referendums, with the majority of their pro-Russian population voting in favor of a split from the largely pro-EU west of Ukraine and another referendum planned for Sunday, 18 May, to join the Russian Federation. It raises the likelihood of, at best, a divided nation and, at worst, a steady decline into civil war.

As reported yesterday, Russia’s Deputy Prime Minister Dmitri Rogozin declared that his country was planning “strategic changes” in its space industry after 2020 and intended to utilize its “intellectual resources” and finances for the ISS for “a project with more prospects.” He also suggested that Russia could use its elements of the space station, independently of the United States and international partners, apparently taunting: “The Russian segment can exist independently from the American one. The U.S. one cannot.” Whether this is a saber-rattling exercise or a serious, active attempt on the part of the Kremlin to destroy arguably the greatest icon of international peacetime co-operation in history is unknown at present. What is clear, though, is the East-West relations are presently at their nadir, and it is a saddening fact of international life and political reality that the shining beacon of the ISS is being drawn into the Ukrainian maelstrom.

Their remarkable voyage began in November 2013, with the spectacular launch of Soyuz TMA-11M from Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan at 9:14:28 a.m. local time Thursday, 7 November (11:14:28 p.m. EST Wednesday, 6 November). Six hours and four orbits later, they docked successfully at the Earth-facing (or “nadir”) port of the Rassvet module and were welcomed aboard by the incumbent, six-member Expedition 37 crew.

Their flight had begun three weeks earlier than originally planned, in order to support a rare “direct handover” of operations between crews. For the first time since 2009, before the end of the shuttle era, no fewer than nine people—Expedition 37 Commander Fyodor Yurchikhin of Russia, together with fellow Russians Oleg Kotov and Sergei Ryazansky, NASA astronauts Karen Nyberg and Mike Hopkins, and Italy’s Luca Parmitano, together with Wakata, Mastracchio, and Tyurin—were aboard the multi-national outpost at the same time. Under normal circumstances, six-person ISS crews follow an “indirect” rotation protocol, whereby a given three-member subset departs the ISS, temporarily reducing the population to three, after which another crew arrives a couple of weeks later to restore it back up to six. In the case of this flight, however, Russia wanted to carry a replica Olympic torch into space, display it ceremonially during an EVA, and bring it back to Earth a few days later, in order that it would form part of the February 2014 opening of the Winter Olympics in Sochi. Plans called for Wakata, Mastracchio, and Tyurin to ferry the torch into space on 6/7 November aboard Soyuz TMA-11M, after which Kotov and Ryazansky would take it outside on their EVA on 9 November and Yurchikhin, Nyberg, and Parmitano would bring it home aboard Soyuz TMA-09M on 11 November.

The presence of nine crew members aboard the station, even for a handful of days, proved difficult in terms of practicalities and life-support capabilities. “It will be a very interesting period of time on-orbit,” Kotov told a NASA interviewer before his own launch, aboard Soyuz TMA-10M on 25 September. “We have not had a direct handover for a pretty long period of time, so nine people will be working on-board the station at the same time. It requires a lot of co-ordination by the commander of the crew. It is like … a situation when a lot of your relatives arrive at your house. Somebody is unpacking. Somebody is just arriving. Somebody is leaving. Somebody is in the backyard planting something. After this work we will need a day or two to relax and to understand what happened.”

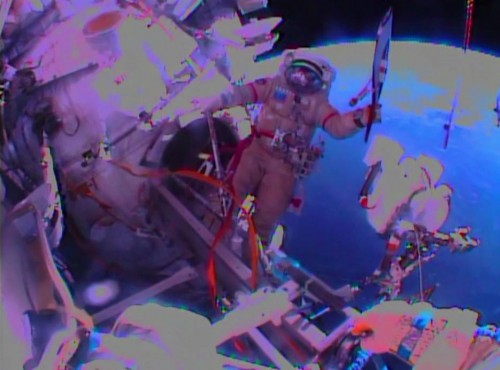

On 9 November, Kotov and Ryazansky ventured outside the ISS for five hours and 50 minutes, during which time they completed a variety of tasks, including the preparation of the Urthecast pointing platform for the installation of a high-definition Earth observation camera, the relocation of a foot restraint, the removal of a microwave radiometry instrument, and photo-documentation of multi-layered insulation on the Russian segment of the station. Although their efforts were frustrated by problems with the foot restraint and the microwave instrument, the two men made headline news around the world when they transmitted spectacular images of the red-and-chrome Olympic torch, backdropped by the blue and white, cloud-speckled Earth.

Two days later, on 11 November, Yurchikhin, Nyberg, and Parmitano—and the torch—returned to Earth aboard Soyuz TMA-09M, closing out their own six-month mission, which had begun in late May 2013. This officially brought down the curtain on Expedition 37, and the new mission, Expedition 38, under Oleg Kotov’s command, got underway. With Kotov, Ryazansky, and Hopkins having been aboard the station since late September, they were already “old hands” and enabled Wakata, Mastracchio, and Tyurin to settle into their new orbital home. In late November, Expedition 38 received its first visitor, the Russian Progress M-21M cargo craft, also known as “Progress 53P” in ISS Program-speak, which was launched from Baikonur. Unlike several earlier Progresses, which supported six-hour, four-orbit “fast rendezvous” profiles, Progress M-21M spent four days and 65 orbits in transit, before docking at the aft longitudinal port of the Zvezda service module on 29 November. During its period of free flight, it evaluated the new Kurs-NA (“Course”) navigation system, which boasts improved performance characteristics, reduced weight, and more efficient power consumption. During its final approach, the Progress retreated to a distance of about 250 miles (400 km) from the ISS, then re-rendezvoused, ahead of docking. Progress M-21M, which will remain attached to the station until mid-June 2014, carried about 5,285 pounds (2,398 kg) of payloads and consumables for the Expedition 38 crew. These included science experiments and EVA equipment to support a planned spacewalk from the Russian segment by Kotov and Ryazansky in December.

In the meantime, the festive season was taking hold and with two Americans (Hopkins and Mastracchio) aboard the ISS, Thanksgiving was observed and celebrated in fine style. The two astronauts described the space station as “the next best place” to spend the holiday if they could not be with their families and friends. They reminisced about past holidays spent on Earth—with Mastracchio reflecting upon his personal tradition of enjoying a big meal and Hopkins noting that he traveled all over the United States to visit family members—before breaking out samples of the foods that they would enjoy with Wakata and their three Russian crewmates. These included turkey, green bean casserole, dehydrated asparagus, baked beans, potatoes, bread, and a selection of beverages and desserts.

As December dawned, all eyes were on ORB-1, the first dedicated Cygnus cargo mission to the ISS, conducted by Orbital Sciences Corp. under the language of its $1.9 billion Commercial Resupply Services (CRS) contract with NASA. Following a highly successful Cygnus demonstration mission (ORB-D) in September 2013, ORB-1 was the first of eight dedicated flights by 2016 to haul a total of 44,000 pounds (20,000 kg) of critical U.S. science payloads, equipment, and supplies to the station. The ORB-1 launch, atop Orbital’s home-grown Antares booster from Pad 0A at the Mid-Atlantic Regional Spaceport (MARS) on Wallops Island, Va., was tentatively scheduled for 18 December, but a sudden deterioration in capability aboard the ISS caused those plans to unravel and raised the likelihood of at least two contingency U.S. spacewalks.

On 11 December, the pump module on one of the station’s two external ammonia coolant loops automatically shut itself down when it reached pre-set temperature limits. Suspicion quickly centered upon the improper functionality of a regulating flow control valve inside the pump module, and the first discussions got underway for an EVA removal and replacement (R&R) of the problematic hardware. A similar failure had occurred in August 2010 and left the ISS with just half of its normal cooling capacity and severely restricted systems redundancy. Three difficult EVAs were performed to remove the failed pump module and restore the loop to full functionality. “When we talk about it in terms of the pump module, it’s going to sound the same to everybody,” explained ISS Mission Operations Integration Manager Kenny Todd. “In that particular instance, we had a pump that just shut down. If you look inside a pump module itself, there are several different components. In this instance, the problem we’re having is with the flow control valve. While it’s in the same housing, it’s a separate piece of hardware and has a different controller. Back in 2010 the pump failed and that was a failure to move the ammonia. What we’re having here is a failure to control the temperature of the ammonia.”

By regulating the temperature of ammonia in the coolant loop, the flow control valve ensures that when it is re-introduced into the heat exchanger of the station’s Harmony node, it does not freeze the water also passing through the exchanger. NASA stressed that the Expedition 38 crew was in no danger, but added that teams moved certain critical ISS systems over the second coolant loop. Some non-critical elements were powered down inside the Harmony node, as well as Japan’s Kibo and Europe’s Columbus laboratory modules, until such time as the problem was resolved.

Whilst awaiting word from NASA, Orbital postponed the ORB-1 launch by 24 hours until 19 December and rolled the Antares vehicle and its Cygnus cargo craft out to Pad 0A to undergo final preparations. However, it was eventually decided that the EVAs would go ahead and a joint decision was taken to delay ORB-1 until January and execute up to three spacewalks (designated U.S. EVA-24, 25, and 26) over Christmas week. Original plans called for each EVA to last 6.5 hours, on 21, 23, and 25 December, and if the third excursion was deemed necessary, and executed on time, it promised to make Rick Mastracchio and Mike Hopkins only the second group of NASA astronauts to have spacewalked on the traditional date of Christ’s birth.

For Mastracchio, his six months in orbit on Expedition 38 and 39 would carry him from being the 27th most experienced spacewalker in the world to just the 5th. On the eve of his first EVA with Hopkins, he had performed six previous spacewalks—aboard shuttle missions STS-118 in August 2007 and STS-131 in April 2010—and had accrued a career total of 38 hours and 30 minutes working in a pressurized suit in the vacuum of space. Hopkins, on the other hand, was making his first spacewalks.

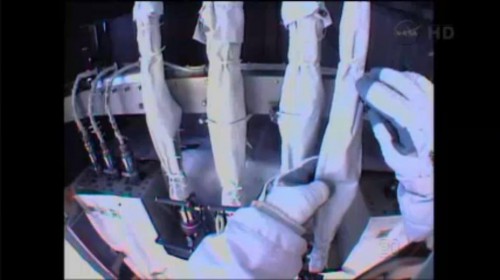

The two men spent five hours and 28 minutes outside the ISS on 21 December and stepped smartly through not only their planned objectives for EVA-24, but also many of the tasks scheduled for the second EVA. After setting up their tools, they removed the failed pump module and, more than 90 minutes ahead of schedule, set to work on the first of their EVA-25 tasks, to move it over to a temporary stowage location on the Payload Orbital Replacement Unit (ORU) Accommodation (POA) on the station’s Mobile Base System (MBS). A third spacewalk was now becoming less likely, and EVA-25 was conducted a day later than planned, on 24 December, during which Mastracchio and Hopkins spent 7.5 hours outside and installed and activated the replacement pump module.

Two Russian EVAs, involving Kotov and Ryazansky, also took place. On 27 December, the two cosmonauts ventured outside the Russian segment in an attempt to install the two UrtheCast medium- and high-resolution Earth-viewing cameras onto the Zvezda service module. The medium-resolution camera was installed in a fixed location, directed toward Earth, whilst its high-resolution sibling was to be attached to a biaxial pointing platform in order to track targets on the surface. However, due to problems with the required telemetry, caused by a poor configuration of internal systems inside Zvezda, the cameras had to be returned to the airlock. Nevertheless, Kotov and Ryazansky spent eight hours and seven minutes in the harsh vacuum of space, marking Russia’s longest EVA to date. A month later, on 27 January, they successfully installed the cameras during a six-hour spacewalk and hooked them up to power and data utilities.

With the ISS back in an acceptable configuration to receive Visiting Vehicles, ORB-1 was launched into orbit on 9 January 2014 and arrived in the vicinity of the space station three days later. It was grappled by the 57.7-foot (17.6-meter) Canadarm2 robotic arm, under the deft control of Hopkins, Wakata, and Mastracchio, and berthed at the Earth-facing (or “nadir”) port of the Harmony node for the next five weeks. Another robotic visitor, Progress M-22M, was launched from Baikonur on 5 February, and docked at the Earth-facing (or “nadir”) port of the Pirs module, following a six-hour, four-orbit rendezvous profile. Six days later, an older cargo craft, Progress M-20M, was undocked and intentionally destroyed in the upper atmosphere, ending its mission. Orbital’s ORB-1 mission came to a similarly fiery conclusion on 18 February, when it was unberthed from the Harmony nadir port and deorbited the following day.

As February wore into March, the return to Earth also loomed for Oleg Kotov, Sergei Ryazansky, and Mike Hopkins, who were coming to the end of their 5.5-month stay aboard the ISS. On 9 March, Kotov ceremonially relinquished command of the station to Wakata, who took the helm as Commander of the new Expedition 39 and became the first Japanese ever to lead a space mission. It represented a truly historic event and offered sterling recognition of the accomplishments of the people of the Land of the Rising Sun. In 39 ISS expeditions since October 2000, no fewer than 20 had been commanded by a Russian cosmonaut, 16 by a U.S. astronaut, and one apiece by a representative of Europe, Canada, and, most recently, Japan.

In wishing his replacements fair winds and smooth sailing, Kotov paid tribute to “a really good increment.” He expressed thanks in English, Russian, and a smattering of Japanese, too, and concluded that he was “really glad to hand command of the station to my friend, Japanese astronaut Koichi Wakata.” The man who has long been nicknamed The Man in the NASA astronaut corps, Wakata replied that he was “humbled” to receive the Expedition 39 command and lauded Kotov’s “outstanding guidance,” Ryazansky’s medical and photographic skills and called Hopkins “the strongest astronaut who ever lived on the space station.” Before the mission, Wakata anticipated a few differences in his daily duties as he transitioned from being an Expedition 38 flight engineer to the man in charge of the safety and success of Expedition 39. “I will be taking the lead as the point of contact in the communications, daily and weekly, with the Mission Control Centers throughout the world,” he told a NASA interviewer, “and also the program management of the International Space Station in the different countries. I need to make sure that everybody in the crew is in a healthy condition and safety comes first and efficiency and also the happiness of the crew members.”

Shortly afterward, Kotov, Ryazansky, and Hopkins boarded their Soyuz TMA-10M spacecraft, undocked from the ISS, and landed safely in Kazakhstan on 10 March, after 166 days in orbit. Meanwhile, aboard the ISS, Wakata, Mastracchio, and Tyurin remained alone for two weeks, before the second half of Expedition 39—Soyuz TMA-12M crewmen Aleksandr Skvortsov and Oleg Artemyev of Russia and U.S. astronaut Steve Swanson—rocketed into orbit from Baikonur on the night of 25/26 March. Theirs was supposed to be a “fast rendezvous” of six hours and four orbits, but complications ensued when a software error hampered the third of four maneuvering system “burns” and Russian mission controllers opted to revert to a standard, two-day, 34-orbit flight profile. Soyuz TMA-12M docked without incident at the space-facing (or “zenith”) port of the Poisk module on 27 March, and Skvortsov, Artemyev, and Swanson brought Expedition 39 up to six-man strength.

In spite of having only been in orbit for a few days, there was precious little time for the new crewmen to adapt to their surroundings. On 9 April, Russia’s Progress M-23M cargo craft arrived, after a six-hour flight, and was expected to be followed shortly afterward by the third dedicated Dragon mission (SpX-3) under the $1.6 billion CRS contract between NASA and SpaceX. The SpX-3 had suffered extensive delays and was finally targeted for a mid-March launch, but was postponed until late March and ultimately until mid-April. It finally roared into orbit atop SpaceX’s Falcon 9 v1.1 rocket from Space Launch Complex (SLC)-40 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Fla., on 18 April. Two days later, in a manner not dissimilar to the ORB-1 Cygnus mission, Dragon performed a textbook rendezvous with the ISS and was grappled and berthed, via Canadarm2, at the Harmony nadir port. It will remain in place until mid-May, whereupon it will depart, but—unlike Cygnus—it has the capability to survive re-entry and bring payloads safely back to Earth.

As Expedition 39 headed into its final few weeks of operations, it might be expected that the SpX-3 mission would be the final swansong. Yet unforeseen events had another card to play for Wakata, Mastracchio, and Tyurin and for their new crewmates Skvortsov, Artemyev, and Swanson. On 11 April, a backup Multiplexer-Demultiplexer (MDM) on the station’s Mobile Base System (MBS) failed and another contingency spacewalk (designated “U.S. EVA-26”) was planned. The MDM is responsible for routing commands to various systems on the inboard truss structure, including the cooling apparatus and radiators. On 23 April, Mastracchio and Swanson spent 96 minutes outside the ISS and successfully replaced the MDM and restored a critical component of the U.S. segment of the station.

All good things must come to an end, and on Monday (13 May), in the Japanese Kibo laboratory, Wakata formally handed over command of the space station to Steve Swanson, who will lead Expedition 40 until mid-September. This allowed the three outgoing crew members, Wakata, Tyurin, and Mastracchio, to concentrate fully upon preparing their Soyuz TMA-11M spacecraft for departure, and at 3:26 p.m. EDT yesterday (Tuesday), following final farewells, the hatches were closed. With Tyurin in command of the Soyuz, undocking occurred at 6:36 p.m. EDT, as the spacecraft flew 261 statute miles (420 km) above Mongolia. About 2.5 hours later, the deorbit burn, lasting four minutes and 41 seconds, was executed at 9:04 p.m. EDT to begin the perilous descent back into the “sensible” atmosphere. The spherical orbital module and cylindrical instrument module of the Soyuz were detached, leaving the three men alone in the beehive-shaped descent module.

Touching down on the desolate steppe, just to the south of the city of Dzhezkazgan, within Kazakhstan’s central uplands, at 9:58 p.m. EDT Tuesday (7:58 a.m. local time Wednesday), Wakata, Mastracchio, and Tyurin ended a mission which had traveled 79 million statute miles (127 million km), completed around 3,000 orbits of Earth, and lasted 187 days, 21 hours, and 43 minutes. Helicopters bearing Russian and NASA recovery personnel reached the landing site shortly afterward to assist the crew and begin with medical examinations. In the aftermath of landing, Wakata and Mastracchio will be flown back to Ellington Field in Houston, Texas, aboard a Gulfstream III aircraft, whilst Tyurin will head back to the cosmonauts’ training at Zvezdny Gorodok (Star City), on the forested outskirts of Moscow.

With the successful landing, the Expedition 39 crew has added significantly to the record books and completed a tremendous amount of robotics and scientific work during their six months in orbit. Completing his fourth space mission, 50-year-old Koichi Wakata—who previously flew twice aboard the shuttle and as an ISS long-duration crewman in 2009—has accrued a career total of 347 days in orbit. This puts Japan in fourth place on the list of the world’s most flight-experienced spacefaring nations. The list is currently topped by Russia, whose Sergei Krikalev has 803 days of cumulative experience, with the United States in second place at 381 days and Germany in third place at 350 days. Japan is now far higher on the table than France (209 days), Canada (204 days), the Netherlands (203 days), Belgium (198 days), and Italy (174 days). The Land of the Rising Sun looks set to retain this fourth-place ranking for at least the next several years.

For 54-year-old Rick Mastracchio, also making his fourth space mission, Expedition 38 and 39 has allowed him to jump, figuratively and literally, from the 27th most experienced spacewalker in the word to the fifth. Prior to his launch aboard Soyuz TMA-11M last November, he had six EVAs and a total of 38 hours and 30 minutes working outside the space station. His EVA-24 with Mike Hopkins on 21 December, which lasted 5.5 hours, pushed him directly up to table into 15th place, whilst the 7.5-hour EVA-25 accelerated him yet further to sixth place, just a few minutes behind the achievement of his former Expedition 37 crewmate, Fyodor Yurchikhin. In making the 96-minute EVA-26 with Steve Swanson on 23 April, Mastracchio pipped Yurchikhin’s record and put himself squarely into fifth place, with nine EVAs totaling 53 hours and four minutes of spacewalking time. Although it was his first long-duration flight, Mastracchio also has 40 days from his three earlier shuttle missions, giving him a total of 227 days of space time overall.

And last but not least, 53-year-old Mikhail Tyurin, who set off aboard Soyuz TMA-11M as the most experienced member of the crew. Making his third mission, he had accumulated more than 344 days on his two previous flights, making him the world’s 34th most experienced most experienced spacefarer. With yesterday’s landing, his total now stands at more than 532 days and establishes him in 13th place. The Expedition 39 crew also became the first ISS crew to all be aged 50 and above at the time of their flight.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace