Continuing a proud heritage of near-perfect mission success, which stretches back across more than a quarter-century, the 153rd Delta II booster broke the shackles of Earth early today (Saturday, 31 January) and successfully delivered NASA’s Soil Moisture Active Passive (SMAP) satellite into a near-circular orbit of about 425 miles (685 km), inclined 98.116 degrees to the equator. Launch was originally planned for Thursday, but was scrubbed during the final hold at T-4 minutes, due to an unacceptable situation with upper-level winds, which violated Launch Commit Criteria (LCC). A 24-hour turnaround was set in motion, but was called off, following the discovery of minor debonds to booster insulation during routine inspections, which required repair. When fully operational, SMAP will utilize a 19-foot-diameter (6-meter) ultra-lightweight mesh antenna to support an active Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) and a passive radiometer, which are tasked with observing clouds and moderate vegetation to measure the presence of water in the topmost 2 inches (5 cm) of soil. It is expected that SMAP will provide global coverage of soil moisture every three days in equatorial regions and every two days at boreal latitudes, above 50 degrees North.

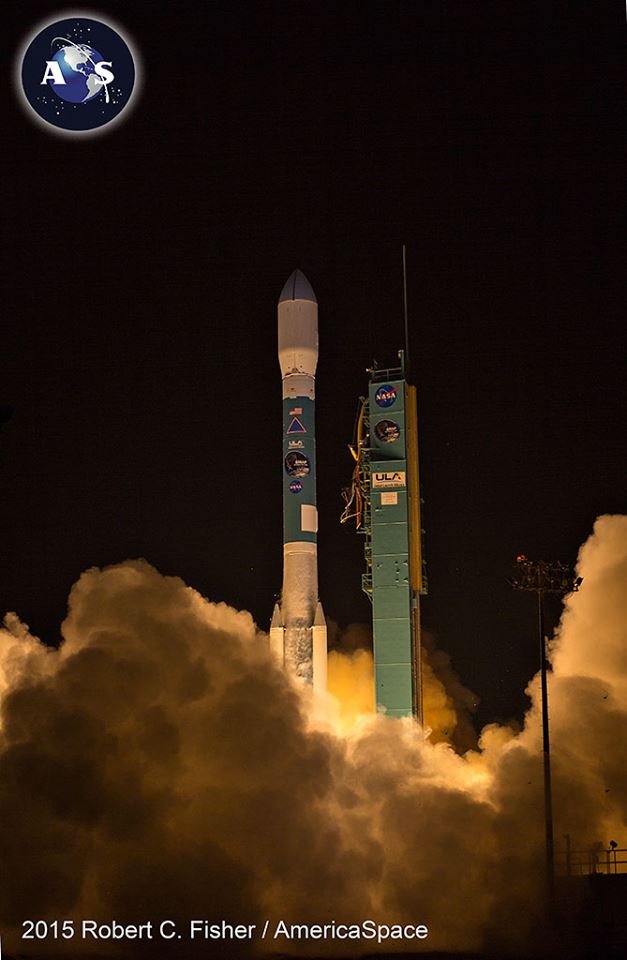

In spite of Thursday’s disappointing scrub, and the need for insulation repairs which scuppered any chance of flying yesterday, Saturday’s launch took place from Space Launch Complex (SLC)-2 at Vandenberg Air Force Base, Calif., at 6:22 a.m. PST, about 40 minutes before local sunrise. Over the course of almost an hour, the two-stage Delta II—which flew in its “7320” configuration, so named to describe its membership of the 7000-series of the vehicle (“7”), its trio of strap-on Solid Rocket Motors (“3”), the presence of a second stage (“2”) and the absence (“0”) of a third stage—powered the 2,080-pound (945 kg) SMAP on a southerly trajectory into orbit, to kick off three years of operations.

Conducted under the auspices of Centennial, Colo.-based United Launch Alliance (ULA), today’s mission enjoyed an 80-percent probability of acceptable weather at the mountain-ringed Vandenberg site, with primary concerns centering upon a possible violation of the Thick Cloud Rule. It was noted by AmericaSpace’s Launch Tracker that conditions were expected to improve still further, to 90-percent favorable, should the backup launch opportunity on Friday, 30 January, have become necessary. As described in AmericaSpace’s preview article, the elements of the Delta II began to arrive in California for processing in July 2014, following by SMAP itself in October, and the pre-flight processing has gone relatively smoothly. However, due to the extreme brevity of the 180-second window needed to get SMAP into its near-circular, near-polar orbit, the exact launch time—to the second—had to be determined before the countdown clock could be released from its final built-in hold at T-4 minutes.

Late Wednesday evening, the Mobile Service Tower (MST)—which protects the Delta II on the pad—was rolled back, exposing the behemoth to the elements and the lenses of the assembled photographers. The danger area around SLC-2 was cleared of all personnel and roadblocks were established at about 2:00 a.m. PST, with the countdown clock holding at T-2 hours and 30 minutes. Shortly thereafter, the vehicle’s guidance system was activated and the helium tanks of the second stage were filled and pressurized. Due to the brevity of the SMAP “window”, which extends for only 180 seconds, it was clear that the launch would be an “instantaneous” one, requiring a precise T-0 to have been established by the time the clock began counting out of the final hold at T-4 minutes.

Finally, at 3:20 a.m., the clock began ticking at T-2 hours and 30 minutes. Following the completion of helium pressurization, the main fuel element for the first stage—a highly refined form of rocket-grade kerosene, known as “RP-1”—was loaded directly into the tanks, a process which required about 25 minutes and was complete by 4:10 a.m. Next came a series of polls to press into the loading of liquid oxygen, which got underway a few minutes after 4:30 a.m., with the super-cold cryogen flowing slowly at first, to ensure that the tank and on-board pipework and valves were fully conditioned, then transitioning to “Fast Fill Mode”. The nature of the liquid oxygen also required all ground equipment to be chilled ahead of loading, in order to prevent thermal shocks and fractures. All liquid oxygen had been loaded by 5:00 a.m., after which the vehicle moved from Fast Fill into “Replenishment Mode”, whereby all boiled-off cryogens were continuously topped-off until close to T-0. This produced a ghostly view for spectators and long-range cameras, for the lower half of the Delta II seemed enshrouded in an eerie grey-white murk.

Aside from the fueling protocols, efforts were well advanced to prepare other Delta II systems for the mission. By 5:15 a.m., the hydraulics were activated and checked out and supported gimbal steering tests of the RS-27A first-stage engine. Just under an hour before T-0, Western Range approval was granted to press ahead with the launch attempt. The countdown pressed on and halted, as planned, at T-15 minutes, at 5:35 a.m., during which time the next-to-last weather briefings took place. At length, all Launch Commit Criteria (LCC) were deemed within acceptable parameters and at 5:53 a.m. the weather was reportedly “Green” (“Go”), with a slight, 10-percent chance that the Thick Cloud Rule might violate an on-time liftoff.

The clock continued counting from T-15 minutes at 5:55 a.m. and the Flight Termination System (FTS)—which would be used to destroy the Delta II in the event of a major accident during ascent—was placed onto internal power and armed. However, as engineers tended to the final needs of a near-perfect vehicle, Mother Nature had her own ideas. By 6:00 a.m., weather balloon data pointed to potentially unacceptable upper-level winds and a few minutes later, at 6:09 a.m. a revised T-0 of 6:22 a.m. was established, about 120 seconds into the 180-second window. The slight delay was due to the upper-level winds, which had turned the Western Range’s status to “Red” (“No-Go”).

Nonetheless, all other vehicle milestones continued and SMAP was disconnected from Ground Support Equipment (GSE) utilities and placed onto internal power, henceforth running on its own batteries until it achieved orbit and deployed its electricity-generating solar array. However, fortune was not on ULA’s side on Thursday, for the final Go/No-Go poll of all stations produced a “No-Go” and a 24-hour scrub, based upon the situation with the upper-level winds. The ground utilities were returned to the vehicle and payload, as ULA recycled to track a second launch attempt during exactly the same window—from 6:20:42 a.m. until 6:23:42 a.m.—on Friday, 30 January. This date soon became untenable and at 1:20 a.m. PST Friday, AmericaSpace’s Launch Tracker noted that “following inspections after de-tanking, there were some minor debonds to the booster insulation discovered”, requiring “an additional day” to effect repairs, which is a “common effect of the cryogenic conditions during tanking and de-tanking of the core booster with [liquid oxygen].” Saturday’s window, like its predecessors, ran for 180 seconds from 6:20:42 a.m.

As a result, today’s attempt offered little more in the way of leeway for technical or weather issues, again demanding a virtually instantaneous launch. Although weather conditions were predicted to be 100-percent favorable at T-0, and remained officially “Green” (“Go”) throughout most of Saturday morning’s countdown, there remained niggling concerns about upper-level winds, with weather balloon data having logged speeds of up to 65 knots. Tanking of the Delta II continued and was complete by 5:10 a.m., after which the liquid oxygen moved from Fast Fill into Replenishment Mode. Like last July’s OCO-2 mission, this countdown was also plagued by foggy weather throughout the night, as related to this author by AmericaSpace’s Mike Killian, who was stationed at Vandenberg with Robert C. Fisher. By 5:56 a.m., just 24 minutes before the opening of the narrow launch window, weather remained “Green”, but upper-level winds—which were gusting at upwards of 70 knots—had led them to be classified as “Red” (“No-Go”).

However, the clock had long since been released from its second-to-last planned hold at T-15 minutes and was heading towards the final hold at T-4 minutes. The FTS was placed onto internal power and armed, the liquid oxygen tanks were topped-off and the Flight Enable Switch was activated. Shortly after 6:00 a.m., the precise time of T-0 was co-ordinated to 6:22 a.m., about 120 seconds into Saturday’s 180-second window, in order that flight controllers could properly analyse the latest weather balloon data. By 6:13 a.m., upper-level winds had relaxed and were reclassified as “Green”, and at 6:18 a.m. the final Go/No-Go polls were concluded and the clock was released from its final hold at T-4 minutes.

Weather conditions were by now 100-percent favorable. Simultaneously, the rocket began to flex its muscles as its ordnance and the pyrotechnics which would fire the three Solid Rocket Motors (SRMs) were armed, external fuel lines were purged, the liquid oxygen load was confirmed at flight pressure and the hydraulics were placed onto internal power. At T-60 seconds, the Launch Director issued a definitive “Go for Launch” and the Range Operations Co-ordinator (ROC) reported “Range Green”.

The Launch Enable Switch was set to “Flight”, at which stage the autosequencer could only be interrupted by a last-moment “Hold! Hold! Hold!” from a member of the launch control team or an abort by the Delta II’s automated systems. SLC-2’s water deluge system was activated at T-45 seconds, flooding the pad surface and flame trench to reduce the reflected energy at the instant of liftoff. The liquid oxygen fill-and-drain valves were closed for flight and at T-2 seconds the RS-27A engine flared to life, gradually building up power to its full sea-level thrust of 200,000 pounds (90,700 kg). Two seconds later came the staccato-like crackle and rich golden flame of the three SRMs and the vehicle was released from SLC-2 to commence its fast climb away from Vandenberg. Such was the nature of the foggy conditions that the vehicle cleared the tower and almost immediately vanished into the murk, before re-emerging later in the ascent to offer a stunning perspective of its pre-dawn rise to orbit.

Each SRM measures 42 feet (12.8 meters) in length and each generated about 110,800 pounds (50,250 kg) of propulsive yield. Together with the RS-27A and a pair of verniers for roll controllability, these powerhouses pushed the Delta II stack rapidly away from SLC-2 and established it onto the proper flight azimuth of 196 degrees to inject SMAP into orbit. Flying in a southerly direction, and traveling out over the Pacific Ocean, the vehicle punched through Mach 1 at T+35 seconds and, at T+50.3 seconds, it encountered a period of maximum aerodynamic stress on its airframe, a phenomenon known as “Max Q”. The trio of SRMs exhausted their powder-based solid fuel and burned out at T+64.7 seconds, but remained attached to the rapidly ascending booster for another half-minute, before being finally jettisoned at T+99 seconds.

After this point, the RS-27A continued to burn, until it shut down at T+261.8 seconds, about 4.5 minutes after departing Vandenberg. Its role in the mission now complete, the first stage—which measured 87 feet (26.5 meters) long—was jettisoned a few seconds later, making way for the ignition of the Aerojet-built AJ-10-118K second stage engine at T+276 seconds. Unlike the RS-27A, the Aerojet engine could be restarted in flight and was tasked with performing two “burns” to deliver SMAP into orbit. Capable of generating 9,850 pounds (4,470 kg) of thrust, the engine was fed by a hypergolic mix of nitrogen tetroxide and a 50-50 combo of hydrazine and unsymmetrical dimethyl hydrazine, known as “Aerozine-50”.

Less than a minute into the first burn, at T+295 seconds, the 27.9-foot-tall (8.5-meter) Payload Fairing (PLF)—a two-piece, bullet-like shroud, responsible for protecting SMAP from aerodynamic, thermal and acoustic stresses in the lower atmosphere—was jettisoned to expose the satellite to the space environment for the first time. The second stage engine shut down for its First Cutoff (SECO-1) at T+643.6 seconds, some 10.5 minutes after launch, and established itself in a temporary “parking orbit”, then coasted for 41 minutes, ahead of the First Restart at T+3098 seconds, almost 52 minutes into the mission. The second burn lasted a mere 12.1 seconds, ending with SECO-2, and was followed by a five-minute period of coasting, which established the proper conditions for the separation of SMAP into orbit at T+3410.5 seconds, or 7:18:50 a.m., just shy of a full hour since it departed Vandenberg. “From the on-board cameras on the Delta Second Stage, the separation and deployment were confirmed,” noted AmericaSpace’s Launch Tracker. “Telemetry indicates that there is positive current from the solar arrays.”

The satellite’s mission is expected to last three years and promises to provide the most accurate and high-resolution measurements of soil moisture ever obtained from space. This is expected to greatly enhance scientists’ knowledge of the processes linking Earth’s water, energy and carbon cycles. Key beneficiaries of SMAP data include hydrologists, weather forecasters, climatologists and agricultural and water resource managers, although the spacecraft is expected provide important assistance in tracking and mitigating fire hazards, floods and disease control.

One of SMAP’s most obvious features is its ultra-lightweight mesh antenna, built by Northrop Grumman, which weighs just 56 pounds (25 kg) and will deploy to a diameter of 19 feet (6 meters) and revolve at 15 rpm, thereby providing a conically scanning beam of 40 degrees, which equates to a swath of 620 miles (1,000 km) of Earth’s surface. Utilizing the mesh antenna will be SMAP’s active radar and passive radiometer, operating in the L-band range (1.20-1.41 GHz), which will utilize a 19-foot-diameter (6-meter) ultra-lightweight mesh antenna—built by Northrop Grumman—to observe clouds and moderate vegetation in order to measure the presence of water in the topmost 2 inches (5 cm) of the soil. It will yield global maps of soil moisture every couple of days.

With thanks to Talia Landman, Mike Barrett and Leonidas Papadopoulos, who supported Thursday’s scrub and today’s successful launch through AmericaSpace’s Launch Tracker.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Missions » SMAP »