With a powerful crackle from its nine Rutherford liquid-fueled engines, Rocket Lab’s Electron booster returned smoothly to flight early Thursday, following a ten-week hiatus in operations. Liftoff of the 56-foot-tall (17-meter), two-stage vehicle took place at 6 p.m. New Zealand Time (2 a.m. EDT) out of Launch Complex (LC)-1 at the southernmost tip of the Mahia Peninsula on New Zealand’s North Island.

In keeping with Rocket Lab tradition, today’s mission bore its own uniquely comical nomenclature—“It’s Chile Up Here”—as it delivered a U.S. Space Force demonstration payload called “Monolith” to low-Earth orbit on behalf of the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) and the Space Test Program (STP). It was Rocket Lab’s second flight in support of Department of Defense objectives, following a previous mission in May 2019.

“Congratulations to all the teams behind Monolith. We’re proud to have safely delivered another mission to orbit for the United States Space Force,” said Rocket Lab founder and CEO Peter Beck. “Programs like the Rapid Agile Launch Initiative are shining a light on the crucial role small launch can play in supporting fast-paced innovation in orbit to support innovation and space capabilities.”

Thursday’s successful flight comes 75 days after another Electron was lost during second-stage flight on the ill-fated “Running Out Of Toes” mission. After lifting off from LC-1 at Mahia on 15 May, the booster enjoyed a smooth first-stage ascent, but around 200 seconds after launch its on-board computer detected “that conditions for flight were not met” and commanded a “safe” shutdown of the single Rutherford second-stage engine. Throughout the anomaly, second-stage performance “remained within the predicted launch corridor” and no harm befell the public or Rocket Lab’s launch and recovery personnel.

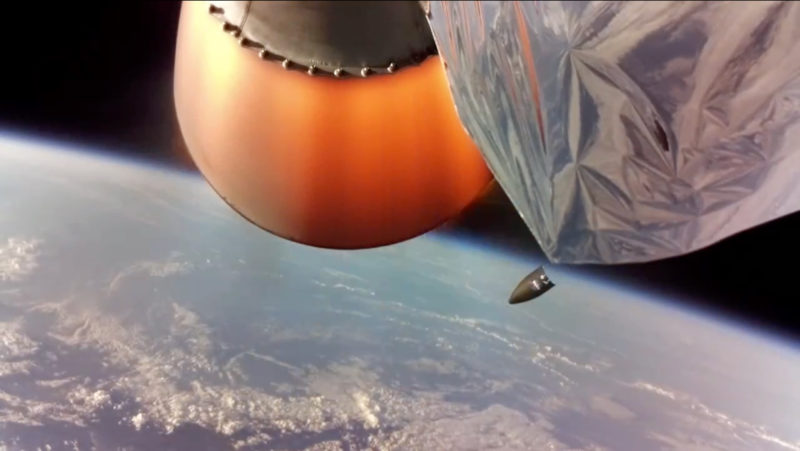

As part of Rocket Lab’s ongoing effort to achieve reusability, the Electron’s first stage safely splashed down in the ocean as intended, successfully trialing a new heat shield which guarded its airframe from heat and high dynamic forces. But the mission’s primary payload— a pair of BlackSky Earth-observation satellites, flying on behalf of Herndon, Va.-based Spaceflight Industries, Inc.—were both lost in the accident.

After the shutdown, good data continued to be telemetered from the second stage, which furnished engineers with a comprehensive understanding of this dynamic phase of the mission. “The behavior” of the second-stage engine, Rocket Lab noted in a 17 May update, “had not been observed previously during…extensive ground testing operations, which include multiple engine hot-fires and full-mission-duration stage tests prior to flight”.

Early in June, as it worked through a comprehensive fault-tree analysis, the Long Beach, Calif.-headquartered launch provider received authorization from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to resume flights.

“With a vehicle with so much flight history and our heavy mission assurance and quality focus, any anomaly was always going to be a complex failure and this one is turning out to be an intricate and layered failure analysis,” said Mr. Beck. “However, we have successfully replicated the failure in testing and determined it required multiple conditions to occur in flight.”

Two weeks ago, in tandem with the FAA and having “scoured thousands of channels of telemetry and systems data”, Rocket Lab completed its investigation and traced the root cause to “an issue” with the second-stage engine igniter. “This induced a corruption of signals within the engine computer that caused the Rutherford engine’s Thrust Vector Control (TVC) to deviate outside nominal parameters and resulted in the engine computer commanding zero pump speed, shutting down the engine,” it was noted.

“The igniter fault resulted from a previously undetectable failure mode within the ignition system that occurs under a unique set of environmental pressures and conditions,” Rocket Lab explained on 19 July. “The issue was not evident during extensive pre-flight testing for this mission, including more than 400 seconds of burn for this particular engine, more than 1,500 Rutherford engine hot-fires to date and 17 successful orbital launches.”

Rocket Lab also noted that it had managed to “reliably replicate” the problem suffered by the Running Out Of Toes mission and “implemented redundancies” into the ignition system, as well as modifications to its design and manufacture, to preclude a reoccurrence.

The 15 May failure was the 20th mission of an Electron, which first flew back in May 2017 and was remotely destroyed by the Range Safety Officer (RSO) due to an erroneous ground software issue. However, the booster sprang back into service, launching 11 successful times between January 2018 and June of last year, putting dozens of small payloads into low-Earth orbit on behalf of civilian, military and commercial clients, including its first classified payload for the National Reconnaissance Office. It can reportedly lift up to 660 pounds (300 kg) to low-Earth orbit.

Last summer, an Electron was lost during second-stage flight, due to an electrical connector malfunction, but Rocket Lab launched six more missions without incident between August 2020 and last March, before running out of luck with Running Out Of Toes in May.

Primary payload for Thursday’s mission—the 21st Electron launch and the program’s 18th fully successful flight—was a research and development satellite known as “Monolith”. Sponsored by the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL), the mission was procured by the Space Force’s Space Test Program (STP), which is headquartered at Kirtland Air Force Base in Albuquerque, N.M. And this location generated the mission’s weird name, “It’s Chile Up Here”, in honor of the beloved green chile of New Mexico.

“Monolith will demonstrate the use of a deployable sensor, where the sensor’s mass is a substantial fraction of the total mass of the spacecraft, changing the spacecraft’s dynamic properties and testing ability to maintain spacecraft attitude control,” Rocket Lab explained. “Analysis from the use of a deployable sensor aims to enable the use of smaller satellite buses when building future deployable sensors such as weather satellites, thereby reducing the cost, complexity, and development timelines.”

Original plans called for Monolith to ride the first Electron out of Launch Complex (LC)-2 at the Mid-Atlantic Regional Spaceport (MARS) on Wallops Island, Va. In doing so, it would become Rocket Lab’s inaugural mission from U.S. soil. Selected by Rocket Lab in October 2018, construction of LC-2 got underway in February 2019 and it was officially opened only ten months later. This location was reportedly picked as the second Electron launch site on account of the wide range of orbital inclinations it can support and Rocket Lab announced its intent to fly as frequently as once per month from LC-2.

In April of last year, an Electron was rolled out to LC-2 and raised to the vertical configuration for a series of integrated systems tests, which included hot-firing the nine Rutherford first-stage engines. And just last September, a Wet Dress Rehearsal (WDR) was conducted at LC-2, which saw engineers complete a fully integrated countdown and fill the Electron with its flight load of rocket-grade kerosene (known as “RP-1”) and liquid oxygen. At the same time, Rocket Lab was granted a five-year Launch Operator License by the FAA to fly Electrons from LC-2.

However, due to a delayed certification of the Autonomous Flight Termination System (AFTS), the Monolith mission was reassigned from LC-2 back to LC-1 at Mahia and launch was correspondingly pushed back from the third quarter of 2020 to this summer.

Payload integration of Monolith into Electron’s fairing was completed on Wednesday and the booster was transported out to the pad. Weather conditions on the Mahia Peninsula were satisfactory, with clear skies and a slight chance of cloudiness towards the end of Thursday’s two-hour window. In the final hours before launch, cryogenic tanking of the Electron with liquid oxygen was concluded and at T-60 minutes Rocket Lab tweeted that its vehicle was suitably “LOX’d and loaded”.

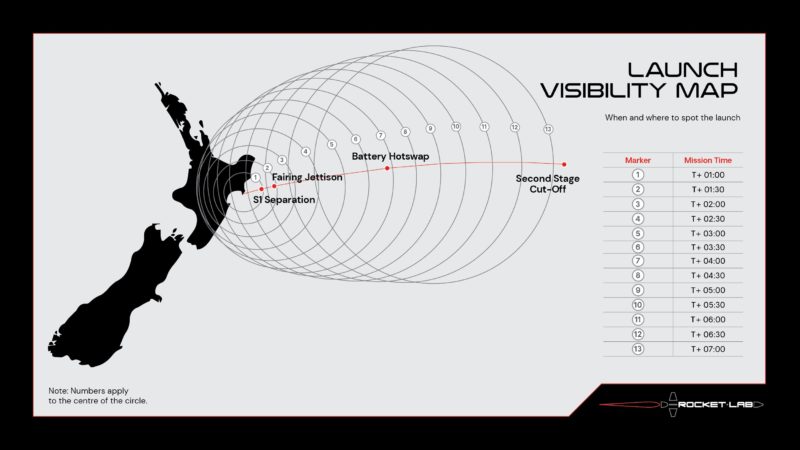

Liftoff occurred precisely on time at 6 p.m. NZT (2 a.m. EDT), with the nine Rutherford engines producing approximately 50,400 pounds (22,800 kg) of propulsive yield to lift the Electron off the pad. A clean ascent saw the separation of the first stage after three minutes, the jettison of the payload fairing shortly thereafter and a smooth burn of the second-stage engine. With those two stages gone, the turn came of the third “Kick Stage”, whose single Curie powerplant—described by Rocket Lab as “our small but mighty, 3D-printed engine”—roared to life to lift Monolith towards its spot in low-Earth orbit, some 370 miles (600 km) in altitude, inclined 37 degrees to the equator. “Payload deployed,” tweeted Mr. Beck. “Flawless launch and mission by the team!”

One Comment

One Ping

Pingback:Rocket Lab’s Electron Booster Returns to Flight, Delivers Monolith Payload to Orbit