The continuous relay of unpiloted resupply craft visiting and departing the International Space Station (ISS) is expected to continue Tuesday, with the launch of Russia’s Progress M-26M atop a Soyuz-U booster from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan. Liftoff of the mammoth Soyuz-U and the Progress—which is laden with around 5,000 pounds (2,270 kg) of equipment and supplies for the incumbent Expedition 42 crew—is presently scheduled to occur from Baikonur’s Site 31/6 at 5:00:17 p.m. local time (6:00:17 a.m. EST), kicking off a well-trodden six-hour, four-orbit “fast rendezvous” profile to reach the space station. Upon docking at the aft longitudinal port of the Zvezda module, Progress M-26M will remain at the ISS through the end of August.

Despite being only six weeks old, 2015 is already shaping up to be an ambitious year for the International Partners, with the launch of the long-awaited One-Year Crew planned for the end of March, the major relocation of ISS hardware in readiness for Commercial Crew operations from June onward, the delivery of the Bigelow Expandable Activity Module (BEAM) in September, a range of human occupants from the United States, Russia, Italy, Japan, Denmark, and the United Kingdom, and as many as eight U.S. EVAs. Dovetailed into these plans, the current Expedition 42 crew—Commander Barry “Butch” Wilmore of NASA, Russian cosmonauts Aleksandr Samokutyayev, Yelena Serova, and Anton Shkaplerov, U.S. astronaut Terry Virts, and Italy’s first woman in space, Samantha Cristoforetti—bade a fond farewell to SpaceX’s fifth dedicated Dragon cargo ship (CRS-5) on Wednesday, 11 February, and the European Space Agency’s (ESA) fifth and last Automated Transfer Vehicle (ATV-5) on Saturday, 14 February.

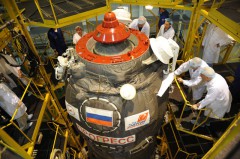

In readiness for the launch of Progress M-26M—also designated “Progress 58P” in the ISS Program nomenclature—the cargo ship was fueled with nitrogen tetroxide and unsymmetrical dimethyl hydrazine (UDMH) propellants and compressed gases in the first week of February, before being transferred to Baikonur’s Spacecraft Assembly and Testing Facility for final processing. Last Thursday (12 February), it was encapsulated within its bulbous payload shroud and the Soyuz-U booster was rolled out to Site 31/6 early Sunday. Surrounded by an eerie midwinter fog and backdropped by a distinctly snowy Baikonur, the vehicle was transported to the pad in a horizontal configuration, before being raised to the vertical.

The Soyuz-U booster is a direct descendent of Chief Designer Sergei Korolev’s R-7 Semyorka (“Little Seven”) missile, and upon arrival at the pad electrical and propellant umbilicals were connected as technicians set to work charging batteries and preparing for fueling operations. The process of loading liquid oxygen and a highly refined form of rocket-grade kerosene—known as “RP-1”—aboard the vehicle is expected to begin about five hours before T-0, after which the Soyuz-U will transition to a “Topping Mode,” whereby all boiled-off cryogens will be rapidly replenished until close to liftoff. This will ensure that the liquid oxygen tanks are maintained at Flight Ready levels, ahead of the ignition of the Soyuz-U’s single RD-118 engine and the RD-117 engines of its four tapering strap-on boosters.

Internal avionics will be initiated and the on-board flight recorders will be spooled-up to monitor the rocket’s myriad systems throughout ascent. At T-10 seconds, the turbopumps on the core and strap-on boosters will come to life and, following confirmation that all engines are burning at full power, the fueling tower will be retracted and Progress M-26M will roar into the evening Baikonur sky, bound for the ISS.

Rising rapidly, the vehicle will pass 1,100 mph (1,770 km/h) within a minute of leaving Site 31/6, during which period the maximum amount of aerodynamic stress—colloquially known as “Max Q”—is expected to impact its airframe. At T+118 seconds, having attained an altitude of 28 miles (45 km), the four strap-on boosters will exhaust their supply of liquid oxygen and RP-1 and will be jettisoned, leaving the core stage and its single engine to continue the ascent. By two minutes into the flight, the Soyuz-U will be traveling in excess of 3,350 mph (5,390 km/h). The payload shroud and escape tower will be discarded, and, four minutes and 50 seconds after leaving Baikonur, the core stage will separate at an altitude of 105 miles (170 km) and the RD-0110 engine of the third stage will ignite to boost Progress M-26M to a velocity of over 13,420 mph (21,600 km/h). By the time the third stage separates, about nine minutes after launch, the vehicle will be in space.

Separation of Progress M-26M from the third stage of the Soyuz-U is expected to take place into a target orbit of about 120 x 152 miles (193 x 245 km), inclined 51.6 degrees to the equator. Shortly thereafter, the process of unfurling the cargo ship’s twin solar arrays and Kurs (“Course”) rendezvous and navigational appendances will commence. Two maneuvering “burns” will be performed during the first orbit of Earth, the first at 5:43:11 p.m. Baikonur time (6:43:11 a.m. EST) and the second at 6:09:41 p.m. Baikonur time (7:09:41 a.m. EST), which will gradually increase the altitude of the spacecraft from 133 x 157 miles (215 x 253 km) to 150 x 164 miles (242 x 264 km). This will be followed by another pair of maneuvering burns during the second orbit, expanding the altitude yet further from 162 x 170 miles (260 x 275 km) to 167 x 185 miles (269 x 297 km). By the time these four burns have been concluded, the proper conditions will have been created for Progress M-26M to follow an automated rendezvous and docking regime to reach the ISS.

Assuming the mission launches on time, docking is anticipated at about 10:58 p.m. Baikonur time (11:58 a.m. EST), some five hours and 58 minutes after launch. Since August 2012 and the flight of Progress M-16M, Russia has sought to deliver the majority of its unpiloted cargo ships to the space station in about six hours, and four orbits, and since March 2013 and the voyage of Soyuz TMA-08M, has endeavored to do with crewed missions. With the notable exception of Soyuz TMA-12M in March 2014, which suffered a software error shortly after orbital insertion and whose crew was obliged to revert to the standard, two-day rendezvous profile, this has enabled much more rapid cargo deliveries and a much more benign environment for human space travelers.

Progress M-26M is expected to remain attached to the ISS for a little over six months, with undocking presently scheduled for 26 August. Upon its arrival, it will join Progress M-25M—launched in October 2014—which is currently docked at the Pirs module and will depart at the end of April. Another Russian cargo craft, Progress M-27M, will launch on 28 April and will be docked at Pirs through early August, followed by the flight of Progress M-28M, which will also call Pirs its home, on 6 August. Planned for at least one ISS orbital correction burn, in March, Progress M-26M will thus clock up 190 days in space by the end of its mission, making it one of the longest-flown of its kind in history.

The Progress program has a storied history. Its development began in 1973 in response to the anticipated problem of resupplying and refueling the Soviet Union’s Salyut 6 space station, whose cosmonauts went on to spend more than six months at a time in orbit. Modeled closely on the Soyuz spacecraft, its interior was redesigned to house foodstuffs, water, experiments, and fuel for the station’s maneuvering thrusters. Since its maiden voyage, Progress has seen many changes, but its role has remained largely unchanged and the numbers speak for themselves. Between its first launch in January 1978 and its most recent flight in October 2014, no fewer than 148 Progresses have roared aloft, of which 12 traveled to the Salyut 6 space station, 13 to Salyut 7, 62 to Mir, and the remainder headed toward the ISS. The vast majority have accomplished successful missions—executing dockings with both occupied and unoccupied space stations—but a handful have also been responsible for several hairy near-misses.

In August 1994, rookie cosmonaut Yuri Malenchenko was in command of Mir when Progress M-24 impacted the station on several occasions, producing a series of slight shocks through the structure, which were felt by the crew. A near-miss by Progress M-33 in March 1997 provided the unfortunate prelude for the flight of its successor, which in late June almost caused catastrophe for the crew and permanently damaged Mir. Progress M-34 had been launched in early April and spent an uneventful 11 weeks docked at the station, before being undocked on 24 June for a series of tests of the TORU rendezvous apparatus. However, the cargo ship collided with Mir, damaging a solar array and permanently depressurizing the Spektr research module.

Since then, Progress has provided a reliable mainstay for the ISS Program. It began its 100th mission on 2 February 2003, launching just a few hours after the tragic loss of shuttle Columbia and the STS-107 crew. During the 2.5 years of introspection which followed the disaster, Progress was the primary means of resupplying the station. The only member of the family which failed to reach its destination entirely was Progress M-12M, launched in August 2011, shortly after the final shuttle mission, which suffered a Soyuz-U engine failure and re-entered the atmosphere over the Altai Republic. A year later, in August 2012, Progress M-16M kicked off the fast rendezvous concept, which has been employed by most of its siblings until the present day.

Over the span of almost four decades, Progress has delivered not only food, water, propellant, and equipment, but also letters, gifts, and treats for the cosmonauts and astronauts of many nations who have occupied Soviet, Russian, and international space stations. Writing in 1998, astronaut Jerry Linenger—one of the handful of U.S. astronauts to reside aboard Mir—recounted the sheer joy of receiving a shoebox full of goodies from his wife and children: “Once found, and munching on fresh apples that had also arrived in the Progress,” he described in his memoir, Off the Planet, “we individually retreated from our work and sneaked off to private sections of the space station, eager to peruse the box’s contents.”

Fellow astronaut Andy Thomas remembered receiving gifts of M&Ms and Oreo cookies, whilst John Blaha once described similar excitement: “Once we found our packages,” he wrote, “it was like Christmas and your birthday, all rolled together, when you are five years old. We really had a lot of fun reading mail, laughing, opening presents, eating fresh tomatoes and cheese.” In more recent times, ISS crew members have also received gifts from home. In February 2008, Peggy Whitson, commander of Expedition 16, remembered crewmate Dan Tani calling one Progress “the onion express,” as the latest delivery of letters from home and fresh foodstuffs arrived.

Shannon Lucid, the first U.S. woman to live aboard Mir, asked her daughter to provide some books for her six-month mission. She received the first volume of a science fiction book aboard a Progress and enjoyed it immensely … with the exception that it ended right on an agonizing cliffhanger. “That was the point that you realized you were just really isolated,” Lucid told the NASA oral historian, “because if I’d been living here, I would’ve gone out immediately and gotten the second volume. I sent a lot of email messages with a lot of threats. I told her that it had better be on the next Progress. So they worked real hard and got it on the next Progress!”

NASA astronaut Norm Thagard, the first American to live aboard Mir, recalled receiving an 11-pound (5-kg) care package aboard Progress M-27 in April 1995 from his family and friends. He videotaped his Russian crewmates as they opened the hatches between the station and the cargo craft. “One of the things you notice is that the air smells different inside the vehicle,” Thagard told the NASA oral historian, “but it’s not any special air supply or anything. I guess it’s just the Baikonur air that was in there.”

In their book Soyuz: A Universal Spacecraft, David Shayler and the late Rex Hall speculated that the term “Progress” may have originated from the implication of having made significant progress in space station operations, although the precise heritage of the name remains unclear. What is clear, though, is that aside from the technical and functional role of Progress over the decades, it has provided an indispensable psychological crutch for dozens of cosmonauts and astronauts—a crutch which has enabled them to overcome the profound isolation of the strange microgravity environment, far from family and friends.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Missions » Progress »