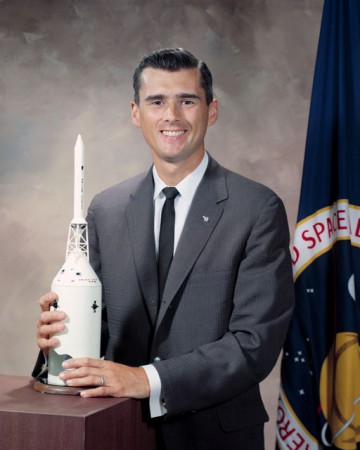

Roger Bruce Chaffee—who would have turned 80 today (Sunday, 15 February)—has been out of this world for far longer than he was ever in it. His life was tragically snuffed out on the evening of 27 January 1967, killed in a horrific fire aboard the Apollo 1 command module on Pad 34 at Cape Kennedy. At the time, Chaffee was barely three weeks shy of his 32nd birthday and just a month away from becoming the youngest American to venture into space at that time. Indeed, had he flown Apollo 1, Chaffee’s accomplishment would have made him the youngest-ever U.S. spacefarer to ride a U.S. spacecraft in history—a record he may have continued to hold until this very day. His story is a fascinating epic of a rising star, cut down in his prime, and the nature and timing of his death is a mournful reflection upon a career tragically shortened and a life lost too soon.

Born in Grand Rapids, Mich., on 15 February 1935, the son of Don and Blanche Chaffee, his interest in aviation began at an early age. His father had been a barnstorming pilot, who flew a Waco 10 biplane and served as chief inspector of army ordnance at the Doehler-Jarvis plant in Grand Rapids during World War II, and it was he who took the young Roger flying over Lake Michigan in 1942. This seeded an ambition in the boy’s mind to become a pilot, and within a few years he and his father were building model aircraft. During this period, Chaffee developed a keen love of guns and hunting from his grandfather and, whilst in the fifth grade, became interested in music and played the French horn, later the cornet, and eventually the trumpet.

He became a Boy Scout in 1948 and earned 10 badges within the year, gaining the accolade of Order of the Arrow. Chaffee subsequently achieved the highest attainable rank of Eagle Scout and taught inexperienced scouts how to swim. In his mid-teens, he became interested in electronics engineering—with mathematics and science, particularly chemistry, considered his favorite subjects—with a future career in nuclear physics a very real possibility. Graduating in the top fifth of his class from Central High School in Grand Rapids in 1953, he applied for scholarships at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Md., the Rhodes Scholarship, and the Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps (NROTC). Since he was not yet sure of a military career, he turned down the Naval Academy, and the Rhodes option did not provide for an engineering degree, which led Chaffee down the NROTC path.

He entered Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago, Ill., in September 1953, and by the end of his first academic year had settled on aeronautical engineering and transferred to Purdue University in Lafayette, Ind. During the summer of 1954, he was scheduled for an eight-week duty aboard the battleship U.S.S. Wisconsin, but almost failed the preparatory training, due to his poor performance in the eye examination. “One eye was so weak that he nearly was failed on the spot,” wrote Mary C. White in a biography of Chaffee for the NASA History Office. “However, the attending physician gave him a break and told him that he would be allowed to retake the test the next morning. Passing the eye test was critical; if Chaffee did not pass the examination, he never would fly professionally. Roger spent part of the long night walking along the shores of Lake Michigan. Before dropping off to sleep, he offered numerous prayers for successful test results. The exam was repeated the next morning. Chaffee passed with flying colors.” During the cruise, he visited England, Scotland, France, and Cuba.

Whilst an undergraduate at Purdue, Chaffee was hired to teach freshman mathematics classes, and it was during this period, in September 1955, that he met the young woman who would later become his wife. Martha Horn hailed from Oklahoma City and, according to C. Donald Chrysler in his 1968 biography, On Course to the Stars: The Roger B. Chaffee Story, reportedly described Chaffee as “a handsome, but smart-alec upperclassman.” Nevertheless, the couple were married in August 1957.

By this stage in his life, Chaffee’s naval career had begun to blossom. He undertook tours during the remainder of his undergraduate period, visiting Scandinavia and embarking on flight training aboard a Cessna 172. He soloed in March 1957 and completed his private flight test in late May, passing with an above average grade of 86 percent, which allowed him to progress into further military flight training. A few days later, in early June, Chaffee received his Bachelor of Science degree with distinction in aeronautical engineering from Purdue, earning a key to the National Society of Engineers in recognition of his performance. “It took me four years to learn how little I knew,” he was quoted by Chrysler. “Knowledge is vast. There is so much more to learn and I am going to take advantage of every opportunity that comes along.” In August, he completed his naval training and was commissioned as an Ensign in the U.S. Navy.

By November, Chaffee had reported for military flight instruction in Pensacola, Fla., where he flew the T-34 Mentor and T-28 Trojan, and later to Kingsville, Texas, for training on the F-9F Cougar jet. During his first year of as a naval aviator, Martha gave birth to their first daughter, Sheryl. In November 1958, he reported for aircraft carrier training, a task whose complexity he likened to “landing on a postage stamp,” and won his wings early the following year. Chaffee worked on the A-3D Skywarrior photographic reconnaissance aircraft, but was in Africa flying when his son, Stephen, was born in July 1961.

He attended Safety and Reliability School in California, which provided him with the necessary training to serve as a safety and quality control officer at the Heavy Photographic Squadron 62 at Naval Air Station (NAS) Jacksonville, Fla. He photographed the launch facilities at Cape Canaveral—the very place where his life would close, a few years hence—and participated in U.S. reconnaissance flights during the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962. On occasion, Chaffee flew as many as three missions per day, photographing Soviet missiles in transit to Cuba, during the period which brought the world within a hair’s breadth of possible nuclear conflict.

With astronaut training as the ultimate career goal, Chaffee joined a pool of 1,800 applicants for the second NASA intake in September 1962. In January of the following year, he entered the Air Force Institute of Technology at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio, to work toward a master’s degree in reliability engineering, but in June 1963 was invited to begin screening for the third class of astronauts. His eye examinations, this time, showed no concerns, although physical testing highlighted a very small lung capacity, but this did not prevent Chaffee’s selection in October. He was on a hunting trip in Michigan at the time and, aged just 28, became the youngest person ever selected by NASA at that point in time for astronaut training.

At the time of his selection, he was a Lieutenant in the Navy and had logged over 2,300 flying hours, more than 2,000 of which were in jets. NASA Group Three was unusual in that it comprised a mix of experimental test pilots, Air Force engineers, ex-military fliers in research roles, and, lastly, two operational naval aviators: Chaffee and Gene Cernan. “In the early days, some tended to underestimate Roger, perhaps because of his small stature,” reflected fellow astronaut Walt Cunningham in his memoir, The All-American Boys, “but he had the capacity to fill a room—any room. It was impossible to attend a meeting with Roger and not be aware of his presence. He had a fighter pilot’s attitude, even though his flying background was in multi-engine photo-reconnaissance aircraft. When confronted with a problem, Roger would bore right in.”

One such problem was one of Chaffee’s initial assignments in the astronaut corps, in which he was detailed to follow spacecraft communications systems and the worldwide Deep Space Instrumentation Facility (DSIF). “With characteristic energy and enthusiasm, Roger plunged into the arcane world of bandwidths and Doppler shifts,” explained astronaut Mike Collins in his autobiography, Carrying the Fire, “making sure the complex equipment was going to do all it was advertised to do and that it was simply and sensibly designed from an operator’s point of view.”

Living in Houston’s Clear Lake suburb, Chaffee brought many of his artistic and engineering talents to bear on the tan duplex which became his new family home. “When Martha asked her husband to build a tiny water fountain in the backyard, she wound up with a carefully engineered waterfall crafted from tons of gravel and hours of backbreaking work,” wrote Mary C. White in her biography of Chaffee. “The cascading waterfall was complimented by the lighting Roger had installed around their pool. Additionally, he wired their stereo system so that music could be heard in any room of the house.”

Chaffee and Gene Cernan were both lieutenants, earning no more $10,000 per annum, but the lucrative astronaut contracts with Life magazine allowed them to buy lots on Barbuda Lane, where they built their houses, side by side, and separated by a thin wooden fence. “We moved in within ten days of each other,” wrote Cernan in his memoir, The Last Man on the Moon. “Roger had the first swimming pool on the block and I built a walk-in bar in my family room, so we became a gathering place for many parties.”

He admiringly described Chaffee as “a workaholic” and noted that the two men frequently went hunting together. Cernan did not possess a rifle of his own, so used one of Chaffee’s hand-crafted creations—a .243 Magnum—which Martha later gave to him as a keepsake. During one hunting trip, with the golfing legend Jimmy Demaret, Cernan endured airsickness and Chaffee teased him mercilessly. “You gonna barf on the way to the Moon, too, Geno?” he asked, all while demonstrating the iron-clad nature of his own stomach by chomping a banana-sized jalapeno pepper in two bites.

After almost 2.5 years of training, in March 1966, Chaffee was named as Pilot of the inaugural manned shakedown flight of the Apollo spacecraft, teamed with Commander Virgil “Gus” Grissom and Senior Pilot Ed White. He would therefore become one of the only members of his class of astronauts to have moved directly into a position on a prime crew, without having first served in a backup capacity. “Roger is one of the smartest boys I’ve ever run into,” Grissom was quoted by The New York Times. “He’s just a damn good engineer. There’s no other way to explain it. When he starts talking to engineers about their systems, he can just tear those damn guys apart. I’ve never seen one like him.”

Yet Grissom’s penchant for colorful language appeared to brush off on Chaffee. Flight Surgeon Fred Kelly, who was a neighbor of the Chaffees in Clear Lake in the mid-1960s, described a distinct change in the young rookie’s mannerisms. “Praise from Gus was hard to come by,” Kelly wrote. “Other astronauts joked that Roger had adopted some of Gus’ characteristics and had even started to use some of Gus’ colorful language that had been foreign to a straight-arrow like Roger.”

As described in a recent AmericaSpace history article, the Apollo 1 crew was killed during a “plugs-out” test of their spacecraft, atop the Saturn IB booster at Pad 34 on 27 January 1967. The fire which raged through the command module probably originated beneath Grissom’s seat on the left side of the cabin, and, although asphyxiation was the primary cause of death, all three men suffered varying degrees of burns. Seated on the right-hand side of the spacecraft, furthest from the point of outbreak, Chaffee—according to Grissom’s biographer, Ray Boomhower—suffered burns which covered about 6 percent of his body surface. Soon after the accident, Fred Kelly’s wife, Jimi, was talking quietly with Martha Chaffee, who expressed a fervent hope that Roger’s face had not been badly burned. “Later, when I returned from the Cape,” recalled Kelly, “I was able to tell her that Roger’s face was untouched by the fire.”

Had Chaffee flown into orbit aboard Apollo 1 on 21 February 1967, as planned, he would have established a new record as the youngest U.S. astronaut yet launched into space, at just 32 years and 6 days old. This would have soundly eclipsed the previous record-holder—Chaffee’s next-door neighbor and good friend, Gene Cernan, who had flown aboard Gemini IX-A in June 1966, aged 32 years and 81 days. When one casts a glance at the subsequent youngest U.S. spacefarers, the current record-holder is Tammy Jernigan, who was 32 years and 29 days old when she launched aboard shuttle mission STS-40 in June 1991. This makes it highly likely that, had Roger Chaffee flown Apollo 1 on the planned date, he would have not only gained the record for the youngest U.S. spacefarer, but would have held onto it for at least a half-century.

Sadly, it was not to be, and Chaffee today lies in Section 3 of Arlington National Cemetery. Had he flown Apollo 1, it remains conjectural where fate might have carried him. He was certainly keen to participate in a lunar landing, although space historian Dave Shayler noted in his book Apollo: The Lost and Forgotten Missions that Deke Slayton, then-head of the Flight Crew Operations Directorate (FCOD), intended to transfer Chaffee to the Apollo Applications Program (AAP), which eventually morphed into the Skylab space station.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Missions » Apollo » Missions » Apollo » Apollo 1 »

As computer technology marches on and makes digital resurrection possible, let us firmly resolve that the book of this fine man’s life not remain forever closed, that he will soon be “Back in the World Again,” as the David Gray song so ably says, and that it is only a matter of time before he will finally get his spaceflight.

Thank you Ben for the EXCELLENT article about Michigan’s own Roger Chaffee. Western Michigan seems to be “fertile ground” for outstanding individuals such as Chaffee, with Al Worden from Jackson, Michigan who was the Command Module Pilot of Apollo 15 and performed an amazing spacewalk during the journey home from the Moon, and Jack R, Lousma, also from Grand Rapids, Michigan (a GREAT individual I had the honor and privilege of meeting) of the second Skylab crew who probably would have been the lunar module pilot of Apollo 20. There is an extensive exhibit about the Apollo 1 tragedy at the Michigan Science Center here in Detroit (as a matter of fact I just visited it yesterday) featuring the Apollo Egress Trainer and the re-designed hatch developed as a result of the disaster. Signs on each seat indicate where each of the men would have sat in Apollo 1 on that fateful day. I have been there many times, and often have seen boisterous young people become quiet and still in front of the crew compartment, perhaps imagining what it must have been like . . . .