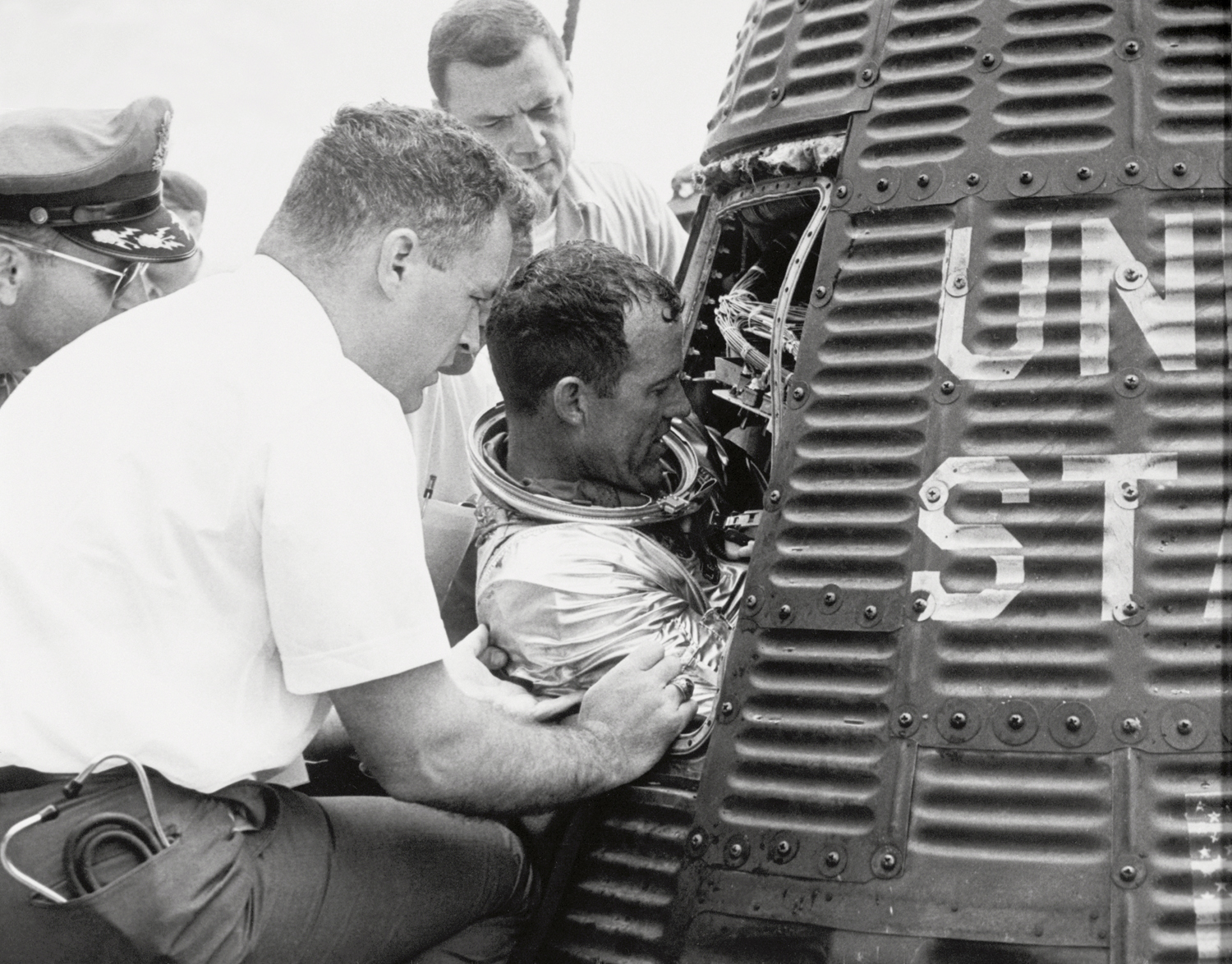

More than a half-century ago, on 15 May 1963, America launched astronaut Gordon Cooper on its longest manned space mission to date. In doing so, NASA began to take strides toward meeting President John F. Kennedy’s goal of landing a man on the Moon before the end of the decade. The humiliation of Yuri Gagarin’s orbital flight had been met by two suborbital missions and three Earth-circling voyages. When Wally Schirra ended his nine-hour, six-orbit flight in October 1962, it was considered so successful that some voices within NASA advised ending Project Mercury immediately and pressing on with the two-man Project Gemini. Others countered that one of Mercury’s goals was to fly an astronaut for more than a day and long-duration experience was highly desirable in the run-up to Gemini. By the end of the year, the space agency was thus hard at work preparing to close out Mercury in style with a “Manned One-Day Mission” (MODM). To history, it would be known as “Faith 7”, and around the colorful man who flew it would grow a legend which endures to this very day.

Originally planned for April 1963, the scope of the mission expanded in the wake of Schirra’s success from 18 to 22 orbits, producing a flight time of around 34 hours in space. To be fair, the MODM would fly for barely a quarter of the Soviet Union’s four-day Vostok 3 mission in August 1962, but its preparations were stupendous. It would demand massive tracking support, including 28 ships, 171 aircraft, 18,000 military personnel, and around-the-clock control operations, headed by veteran flight directors Chris Kraft and John Hodge. Finally, on 14 November 1962, NASA announced that astronaut Gordon Cooper would fly the MODM, with Alan Shepard as his backup.

Yet the months before the flight were marred with difficulty. The military “F-series” version of its Atlas rocket had suffered two inexplicable failures, and when Cooper’s “D-series” booster rolled out of the factory in January 1963 it did not pass its initial inspection. After extensive rewiring of its flight controls, NASA reluctantly announced on 12 February that the launch would be delayed from mid-April until mid-May. To support the astronaut for more than a day in orbit, the Mercury capsule carried better batteries, additional oxygen, extra cooling and drinking water, more hydrogen peroxide fuel, a full load of life-support consumables, and an expansive scientific payload. One plan even called for the replacement of Cooper’s fiberglass couch with a lightweight hammock, but fears that it might stretch and the astronaut might “bounce” meant that the proposal was never approved.

Speaking at a press conference on 8 February, Cooper described his mission as “practically a flying camera”. Firstly, a slow-scan television had been installed into the capsule to monitor the astronaut and his instruments and a battery of other cameras would be aboard: a 70 mm Hasselblad, a specially modified 35 mm device to observe the “zodiacal light” and a 16 mm all-purpose motion picture unit. Cooper himself would wear an upgraded space suit, with a mechanical seal for his helmet, together with new gloves and a more mobile torso. His boots were integrated to make them more comfortable and the whole ensemble was much less bulky than earlier suits.

By the middle of March, the mission—officially dubbed “Mercury-Atlas-9”—appeared to be back on track, when the Atlas booster passed its acceptance trials without a single minor discrepancy. Several weeks later, on 22 April, the capsule itself was attached to the top of the rocket. After much consideration, Cooper had named his spacecraft “Faith 7” to symbolize “my trust in God, my country, and my teammates.” Within the higher echelons of NASA, concerns were raised about the name. (A mission failure, the Washington Post told its readers, could yield unfortunate headlines, such as “The United States today lost Faith”.)

In tandem with Cooper’s preparations, there was also consideration given to attempting a “Mercury-Atlas-10” mission, flown by Alan Shepard for up to three days, to slightly close the space-endurance gap with the Soviets. As part of NASA’s Project Orbit in February 1963, tests had already demonstrated that the Mercury capsule could theoretically support a four-day mission, although the effects of freezing or sluggishness in its hydrogen peroxide thrusters remained unknown. Shepard, of course, was in favour of a three-day flight, and had already named his spacecraft “Freedom 7-II”. Had it gone ahead, it would have launched sometime in October 1963, and Shepard even went so far as to lobby President John F. Kennedy for support, although the president rightly deferred the issue to NASA Administrator Jim Webb. “After Cooper finished his mission,” Shepard reflected in a February 1998 NASA Oral History interview, “there was another spacecraft, ready to go. My thought was to put me up there and just let me stay until something ran out—until the batteries ran down, until the oxygen ran out, or until we lost a control or something; just an open-ended kind of a mission.”

As history has shown, Freedom 7-II would never fly. On 11 May 1963, Julian Scheer, NASA Deputy Assistant Administrator for Public Affairs, emphatically declared this fact and Jim Webb endorsed it, arguing that Gemini was already primed for long-duration missions. His rationale was that it was pointless to demonstrate a capability just once, with an obsolete system. Moreover, an accident on Shepard’s flight could set Project Gemini back in its tracks. In mid-June, the flight officially vanished from consideration and its spacecraft was put into storage. By then, Gordon Cooper had flown his 34-orbit mission, marking an end of the beginning in America’s conquest of space.

Cooper had almost missed out flying in Project Mercury entirely. Since his selection as one of the nation’s first seven astronauts in April 1959, he had gained a reputation as something of a hotshot—a daredevil pilot with a passion for fast cars—balanced against criticisms that he was a complainer who pulled dangerous stunts. (On one occasion, his F-106 Delta Dart jet screamed right outside, and below, the office window of Project Mercury Operations Director Walt Williams.) Even fellow astronaut Deke Slayton wrote of his personal surprise that Cooper had even been picked as an astronaut. “My first reaction was, something’s wrong,” Slayton wrote in his autobiography, Deke, co-authored with Michael Cassutt. “Either he’s on the wrong list, or I am.” Cooper was an engineer at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., and was not even a test pilot.

Still, the man who would fly the final Mercury mission was all but born in a pilot’s seat. His father, an Air Force lawyer and county court judge, frequently plopped his young son on his lap in the cockpit of an old Command-Aire biplane and Cooper took the controls for the first time aged only six. By his teens, the boy was taking lessons in a J-3 Piper Cub and soloed, “officially”, at 16. The story of Cooper’s life was very much a story of his love affair with aviation. Even in his mid-seventies, he told an interviewer that “I get cranky if I don’t fly at least three times a month!”

His love of fast cars was also legendary, as flight director Gene Kranz, arriving at Cape Canaveral for his first day at work, related. “After the plane rolled to a stop,” Kranz wrote, “a shiny new Chevrolet convertible wheeled to a halt just beyond the wing tip. An Air Force enlisted man popped out, saluted and held open the car’s door for a curly-haired guy in civilian clothes, a fellow passenger who deplaned ahead of me.” The curly-haired man offered Kranz a lift to the Cape. Quickly, he “peeled into a 180-degree turn and raced along the ramp for a hundred yards, my neck snapping back as he floored the Chevy. I had never driven this fast on a military base in my life!” For a few minutes, Kranz wondered if he had a madman behind the wheel, as the guy seemed to break every rule in the book and had no fear of being pulled over by the Air Police. Hitting the highway, he made a wide turn and took a hard left, burning rubber. After joyfully yelling Eeee-hah at the top of his lungs, he turned and offered his hand to Kranz.

“Hi, I’m Gordo Cooper.”

Kranz had not only met his first Mercury astronaut, but perhaps the most controversial Mercury astronaut of them all.

With a background in the Marine Corps, the Army and the Air Force and a wife, Trudy, who was also a qualified pilot, Cooper flew F-84 Thunderjet and F-8 Crusader jets in West Germany and served as a project engineer for the F-102 Delta Dagger and F-106 Delta Dart. On one occasion, several years before they became astronauts, he and another Air Force pilot, Virgil “Gus” Grissom, were aboard a T-33 together when it crashed off the end of the runway at Lowry Air Force Base in Denver, Colo. Thankfully, neither man was hurt. In early 1959, both men received mysterious classified orders to attend a briefing in Washington, D.C. After completing a battery of punishing physical and psychological tests for Project Mercury, Cooper was so confident that he would be chosen that he told his boss to start looking for a replacement and requested two weeks’ leave to move his family across country to Langley, Va. When NASA called him to ask how soon he could get to Langley, Cooper’s response was “How about now?”

As an astronaut, though, his early days were somewhat less illustrious and led several senior managers to consider bypassing him for a space mission. They regarded him as an unpredictable complainer, with a seemingly indifferent stance toward the public image that NASA wanted its astronauts to extol. Cooper protested about the lengthy periods away from his family, about the lack of opportunity to fly fast jets and collect flight pay, and he even threatened to leave the program when Deke Slayton was dropped from his own Mercury mission by a heart murmur. Flying a chase aircraft over the Cape during Gus Grissom’s launch in July 1961, Cooper buzzed the launch site, momentarily disrupted communications traffic and earned himself a ticking-off from his boss. On another occasion, flying to Huntsville, Ala., he landed on a runway that was too short and asked to be refueled. When the ground crews told him that it was too dangerous for him to take off again, Cooper shrugged, took off regardless, and made it to his destination with fumes in his tanks!

Even in the weeks preceding Faith 7, there were persistent stories in the press that Cooper might be pushed aside in favour of his backup, Alan Shepard. So shaky was Walt Williams’ “faith” in Cooper that he approached Shepard, several months earlier, and strongly hinted that he might be tipped to fly instead. Believing the mission to be his, Shepard trained feverishly, but Deke Slayton—removed from his own flight only months earlier—felt that Faith 7 belonged to Cooper. Others agreed that it would look bad for NASA if the astronauts were swapped so soon before launch. A timely intervention by Wally Schirra (who threatened to raise the roof if Cooper was overlooked) certainly helped matters, but Walt Williams was convinced that Shepard could do a better job.

As partial compensation, Williams half-promised Shepard a three-day Mercury mission, which ultimately never transpired. Shepard later gained his revenge on the operations director, by lending him the keys to his Corvette. As Williams drove away, Shepard phoned the base’s security office to tell them that “someone” had just stolen his car…

Despite having finally secured the mission as his own Cooper was possibly reacting to pent-up frustration when he took a flight in an F-106, two days before his scheduled 14 May 1963 liftoff. To the great surprise of Williams and Chris Kraft, the astronaut made a very low pass over the Cape. “We were talking,” Kraft recalled of that quiet Sunday afternoon in Williams’ office, “and a sudden roar came upon us. The roar was a jet airplane diving onto the Cape at a very high rate of speed, which was forbidden.” Glancing out of the window, they saw Cooper in the pilot’s seat, as he flew beneath the second-floor office window. Since the Cape was restricted airspace, the switchboard quickly lit up with frantic emergency calls. Williams went berserk and threatened to have Cooper’s “ass on a plate”.

The furious operations director called Slayton, who was by now in charge of the astronaut corps and Cooper’s immediate boss, to demand action. He had to shout to be heard over the din of the F-106. (Williams even phoned Alan Shepard to ask if he was ready for launch.) For his part, Slayton harbored severe reservations about Cooper, but refused to yank him off the mission. Both he and Williams allowed the astronaut to sweat about his flight status for 24 hours, and not until the evening of the 13th did the operations director finally relent and agree to let him fly. Cooper’s supporters regarded the incident as the action of a good, smart pilot and a man with a mission “to go a little bit higher and a little bit faster”.

On Faith 7, he would fly higher and faster than ever before.

The second part of this article will appear tomorrow.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

I remember one newspaper headline following Cooper’s splashdown, “Cooper Super on 22 Looper.”

Hard to believe someone could get away with that kind of behavior. It would never be tolerated in any way shape or form in the present day. And that is not really a bad thing when you consider how much damage an unstable individual can do. Not that Gordo was certifiably unstable- he might have just known what he could get away with and liked to play the game.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cavalese_cable_car_disaster_%281998%29