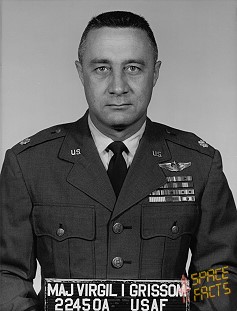

Had Virgil “Gus” Grissom lived longer, wrote Deke Slayton in his autobiography, Deke, he would have been the first man on the Moon. Slayton found himself in charge of the selection and training of astronauts for the two-man Gemini and Moon-bound Apollo missions by late 1962. After Grissom’s death in the Apollo 1 fire, it was Slayton who ultimately chose Neil Armstrong to command the first manned lunar landing. Yet, he wrote, “had Gus been alive, as a Mercury astronaut, he would have taken that step … my first choice would have been Gus.” Grissom was America’s second man in space, the first astronaut to eat a corned beef sandwich in orbit, and a man who fiercely guarded his privacy. “Betty and I run our lives as we please,” he once said. “We don’t care about fads or frills. We don’t give a damn about the Joneses.”

Fifty-five years ago, this week, America delivered its second citizen beyond the “sensible” atmosphere and into space. Grissom’s mission—like that of his predecessor, Al Shepard—lasted barely 15 minutes and achieved suborbital flight. It was a far cry from the complete Earth orbit accomplished by the first man in space, Russia’s Yuri Gagarin, but it demonstrated that America was definitively in the game of human space exploration.

Born in the Midwestern town of Mitchell, Ind., Grissom was small for his age and was nicknamed “Greasy Grissom” as a child, but grew up with a determination to “prove I could do things as well as the big boys.” His father worked for almost a half-century on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and Grissom, too small to participate in school sports, eventually established himself as a Boy Scout, where he led the Honor Guard. He delivered newspapers and, in the summertime, picked peaches and cherries for local growers to earn enough money to date his school sweetheart, Betty Moore, whom he married in July 1945. By this time, he had left school—described by his principal as “an average, solid citizen, who studied just about enough to get a diploma”—and served a year as an aviation cadet. His hopes of joining the theater of war evaporated when Japan surrendered.

Unwilling to fly a desk, Grissom left the U.S. Air Force and took a job installing doors on school buses, before studying mechanical engineering at Purdue. Whilst there, his wife worked as a long-distance operator and Grissom flipped burgers at a local diner. He received his degree in 1950, crediting Betty for making it possible, and re-enlisted in the Air Force, finished cadet training, and won his wings the following year. His completion of training coincided with the outbreak of war in Korea, and Grissom soon found himself in the thick of the conflict for six months, flying a hundred combat missions in sleek F-86 Sabre jets.

An interesting tale surrounds his early days in Korea. Each morning, the pilots rode an old school bus from the hangar to the flight line and only those who had been involved in air-to-air combat could sit. The uninitiated had to stand. Grissom stood only once.

His first taste of war came as a surprise—“For a moment, I couldn’t figure out what those little red things were going by,” he said later, “then I realized I was being shot at!”—and he returned to the United States to be awarded both the Air Medal with a cluster and the Distinguished Flying Cross. Subsequent assignments, which he actually considered more dangerous than combat flying, included instructing new cadets at Bryan Air Force Base in Texas, studying aeronautical engineering at the Institute of Technology at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, and being chosen in October 1956 for Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif. By this time, Grissom had earned a reputation as one of the best “jet jockies” in the service, with more than 3,000 hours of flight time, and was also father to two young boys.

When the Soviets launched Sputnik in late 1957, Grissom took notice, but was far too preoccupied with his job of wringing out new jets at Wright-Patterson to give much consideration to space travel. Then, a little over a year later, he received a teletype message, labeled “Top Secret,” which instructed him to go to Washington, D.C., in civilian clothes for a classified briefing. Mystified, Grissom found that he had been picked as one of 110 candidates for “Project Mercury”—the initiative to send a man into space—and the events of 1959 would truly change his life. “I did not think my chances were very big when I saw some of the other men who were competing for the team,” he said later. “They were a good group and I had a lot of respect for them, but I decided to give it the old school try and take some of NASA’s tests.” Whilst at Wright-Patterson Aeromedical Laboratory, undergoing test after test, his run on the treadmill had to be stopped abruptly when his heart soared to almost 200 beats per minute. On the other hand, he endured the heat chamber perfectly, keeping cool by reading a dog-eared copy of Reader’s Digest, “to keep from getting bored.”

He nearly flunked, when the doctors discovered he was a hay fever sufferer, but Grissom, without missing a beat, convinced them that the absence of ragweed pollen in space probably would not be a problem. He viewed the psychological tests as illogical. “I tried not to give the headshrinkers anything more than they were actually looking for,” he said. “I played it cool and tried not to talk myself into a hole.” Fortunately for Grissom, “talking” was not one of his strengths. Astronauts and managers recalled that he rarely spoke unless he had something to say, and during a visit to the Convair Corp. in San Diego, Calif.—prime contractor for Project Mercury’s Atlas rocket—he told workers to “do good work.” Ironically, those three words turned into a motto of incalculable value to the Convair workforce.

Even after his selection as one of the “Mercury Seven”—alongside Scott Carpenter, John Glenn, Gordon Cooper, Wally Schirra, Al Shepard, and Deke Slayton—Grissom would privately question why he had volunteered to fly a bomb-carrying missile into space. The answer came instantly: “I happened to be a career officer in the military and, I think, a deeply patriotic one. If my country decided that I was one of the better-qualified people for this new mission, then I was proud and happy to help out.” However proud he might have been, one thing that Grissom despised was the moniker of “astronaut.” In his mind, it had an irritating PR undertone. One day, his frustration with the title boiled over: “I’m not ass anything,” he said. “I’m a pilot. Isn’t that good enough?”

On 21 July 1961, he would put his skills to the test … and he almost lost his life in the process.

The second part of this article will appear tomorrow.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

“Had Virgil “Gus” Grissom lived longer, wrote Deke Slayton in his autobiography, Deke, he would have been the first man on the Moon.”

Ye ghods, I want that world so bad I can taste it.