Six decades ago today, John Glenn became the first American to orbit the Earth. His four hours and 55 minutes spent inside a tiny Mercury capsule that he had named “Friendship 7” galvanized a new generation to push ahead with President John F. Kennedy’s goal of landing a man on the Moon before the end of the 1960s. Yet Glenn’s three-orbit mission on 20 February 1962 almost cost him his life.

By the dawn of that momentous year, two other Americans—Al Shepard, the nation’s first man in space, and Virgil “Gus” Grissom—had each completed a 15-minute suborbital “hops” in their respective Mercury capsules, Freedom 7 in May 1961 and Liberty Bell 7 the following July. Despite the national success of achieving human spaceflight, both voyages paled in comparison to the Soviet Union’s first two piloted Vostok missions, during which cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin orbited Earth in April 1961 and Gherman Titov spent a day aloft the following August. In fact, it was Titov’s mission which intensified the urgency to “get America orbital” as soon as possible, transitioning from the Mercury-Redstone rocket to the more powerful Mercury-Atlas launch vehicle.

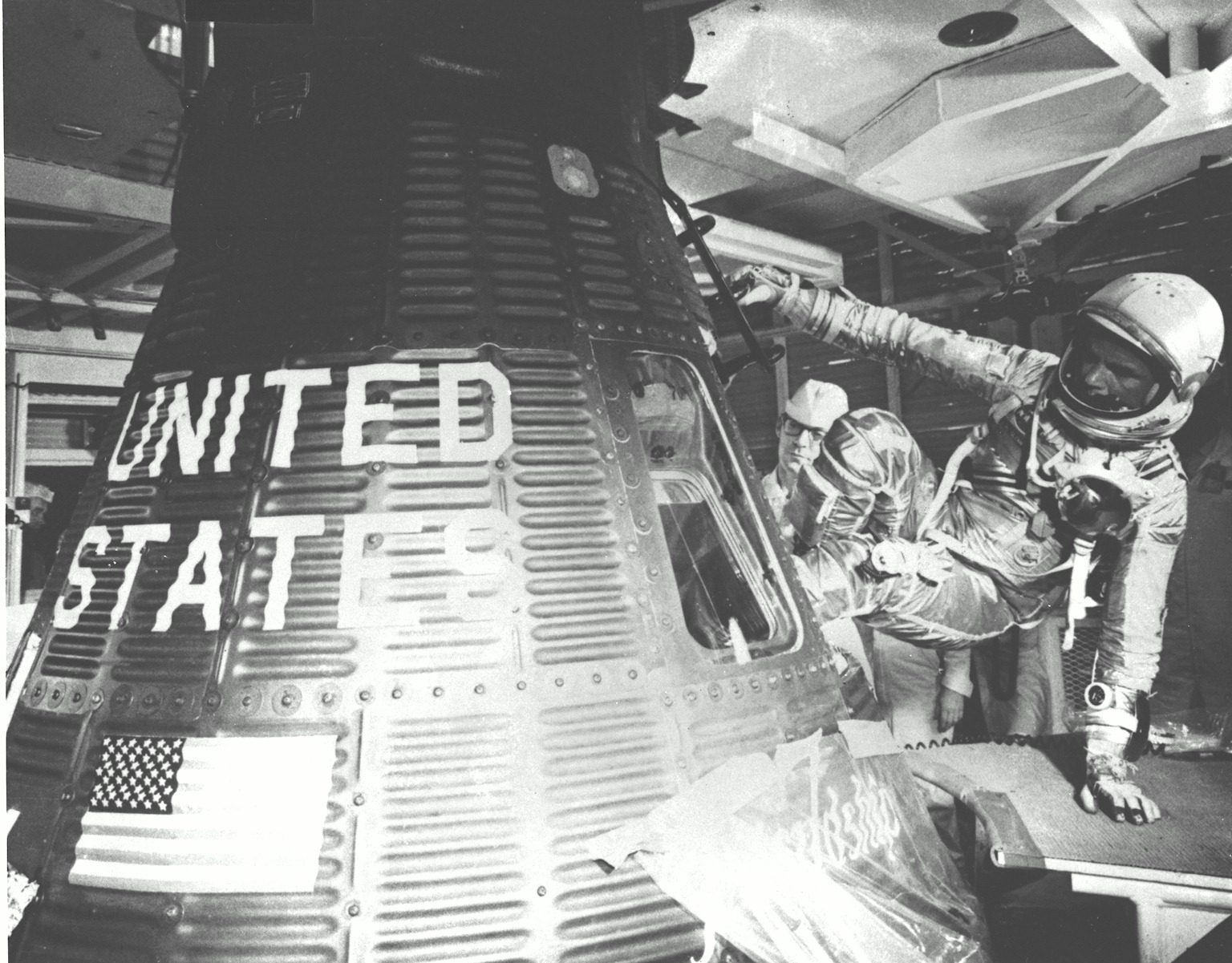

Originally scheduled to fly in December 1961, Glenn and his backup, fellow astronaut Scott Carpenter, found the mission postponed to January of the following year, due to minor technical troubles. In keeping with Project Mercury tradition, Glenn named his spacecraft “Friendship 7”, drawing inspiration from his children, Dave and Lyn, and he asked NASA artist Cecilia Bibby to inscribe the lettering in script-like characters.

More delays afflicted Friendship 7 in early 1962, as technical issues and poor weather pushed the mission into the second half of February. On the morning of the 20th, Glenn was awakened to a gloomy weather forecast and proceeded through suiting-up for his flight. By 7 a.m. EST, he was alone, strapped atop the Atlas and, remarkably—in view of the booster’s lukewarm success record—his pulse varied from 60-80 beats per minute.

“I could hear the sound of pipes whining below me as the liquid oxygen flowed into the tanks and heard a vibrant hissing noise,” he said later. “The Atlas is so tall that it sways slightly in heavy gusts of wind and. In fact, I could set the whole structure to rocking a bit by moving back and forth in the couch!”

At 9:47:39 a.m. EST, with a thunderous racket that overwhelmed Scott Carpenter’s up-tempo call of “Godspeed, John Glenn”, the Atlas’ hold-down posts separated and the enormous rocket began to climb.

“The Atlas’ thrust was barely enough to overcome its weight,” he wrote in his autobiography, John Glenn: A Memoir. “I wasn’t really off until the umbilical cord that took electrical communications to the base of the rocket pulled loose. That was my last connection with Earth. It took the two boosters and the sustainer engine three seconds of fire and thunder to lift the thing that far. From where I sat, the rise seemed ponderous and stately, as if the rocket were an elephant trying to become a ballerina.” By 9:52 a.m.—five minutes after liftoff—Friendship 7 was “through the gates” and Glenn was heading for orbit.

Although he was able to describe the magnificent views he was seeing, it was on this mission that the rest of the world was also able to capture something of the grandeur of Earth, thanks to a camera. Months earlier, whilst getting a haircut in Cocoa Beach, Glenn had seen a little Minolta in a display case. It had automatic exposure and he bought it on the spot for $45. NASA technicians adapted it for the spacecraft and Glenn found that it was the easiest camera to use, even wearing his pressure suit gloves.

Achieving orbit that morning, sixty Februaries ago, Glenn uttered the immortal words for which he would be most remembered. “Zero-G and I feel fine,” he exulted. “Capsule is turning around,” he added as Friendship 7 slowly swung into the re-entry attitude. “Oh, that view is tremendous!” he exclaimed as the horizon appeared in the window and he caught his first sight of the curvature of the Earth and the fragile atmosphere.

After checking his blood pressure for the Canaries ground station, Glenn turned his attention to photographing selected spots on Earth’s surface. Next came further checks of his attitude controls, followed by exertion tests with a bungee cord attached beneath the instrument panel and then reading the vision chart at eye-level. Glenn’s vision, it seemed, was not changing. Head movements, too, did not cause him any disorientation.

Forty minutes into the mission, Friendship 7 drifted into darkness. A sunset from space was one of the aspects of the flight about which he was most excited. “Above” him, the sky was absolutely black, although he could see stars and identified the Pleiades cluster. Then, as Friendship 7 passed directly over Perth and Rockingham, in Australia, Capcom Gordon Cooper asked him if he could see lights. “I can see the outline of a town,” he replied, “and a very bright light just to the south of it.” Glenn thanked the residents of Perth for turning on their lights to greet him.

Traveling over the South Pacific, midway between Fiji and Hawaii, he lifted his visor and gobbled some apple sauce from a toothpaste-like tube, then some malt tablets. As he approached orbital sunrise, Glenn was surprised to see around the capsule a huge field of particles, like thousands of swirling fireflies.

“They were greenish-yellow in color,” he said later. “They were all around me and those nearest the capsule would occasionally move across the window, as if I had slightly interrupted their flow.” The particles diminished in number as he flew eastwards into brighter sunlight and were later attributed to ice crystals venting from Friendship 7’s heat exchanger.

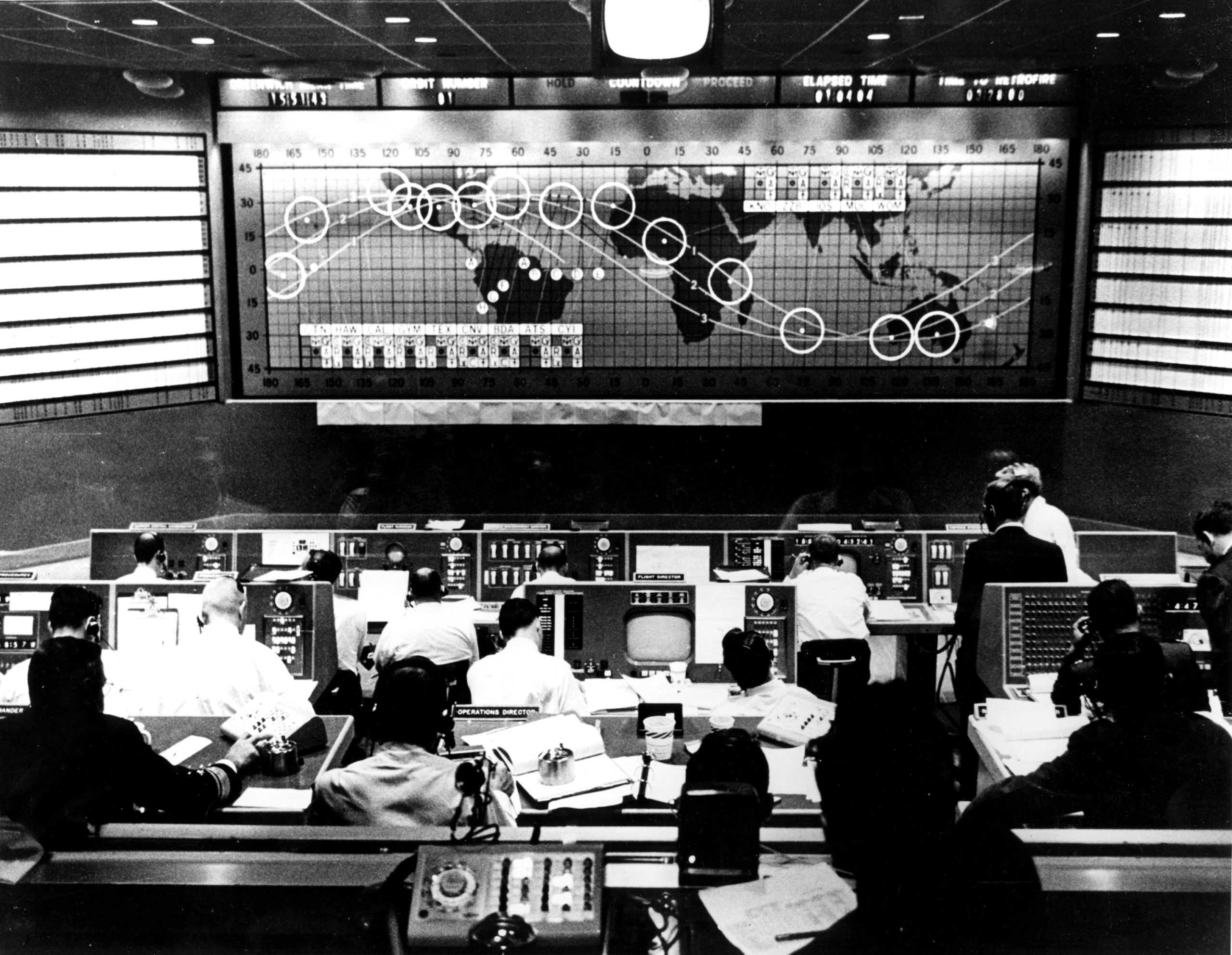

Meanwhile, Glenn continued putting his capsule through its paces. It was shortly after passing the two-hour mark of the mission, however, that he received an odd request from Mercury Control: to keep the switch for Friendship 7’s landing bag in the OFF position. He confirmed that the switch was indeed off and pressed on with his work. Later, Cooper asked him to confirm it again. Then, during another pass, Glenn overheard an indication from a flight controller that his landing bag—located between the base of the spacecraft and the heat shield—might have inadvertently deployed.

He was assured that the ground was monitoring the situation. Glenn began to suspect that the fireflies might be related to some shifting of his heat shield. As early as the second orbit, telemetry engineer William Saunders noted that “Segment 51”—an instrument providing data on the landing system—was exhibiting unusual readings and Mercury Control instructed all tracking sites to monitor it carefully.

Four hours into the flight, however, it became clear that the landing bag was either deployed or improperly locked into position. Whilst over Hawaii, the capcom informed Glenn that the signal was probably erroneous, but, to be sure, asked him to set the landing bag switch in its “auto” position.

“Now, for the first time, I knew why they had been asking about the landing bag,” Glenn wrote. “They did think it might have been activated, meaning that the heat shield was unlatched. Nothing was flapping around. The package of retrorockets that would slow the capsule for re-entry was strapped over the heat shield. But it would jettison and what then? If the heat shield dropped out of place, I could be incinerated on re-entry.”

If the green landing bag light came on, it would clarify that it had indeed accidentally deployed. However, “if it hadn’t, and there was something wrong with the circuits, flipping the switch to automatic might create the disaster we had feared”.

He flipped the switch. No light came on.

This suggested that the landing bag was secure. As retrofire approached, Capcom Wally Schirra, based at Point Arguello in California, told Glenn not to jettison his retrorocket package at least throughout his passage across Texas. It marked the first of several efforts to ensure that, if the heat shield had been loosened, the retrorocket package might hold it in place just long enough to survive the hottest part of re-entry.

Six minutes before retrofire, Glenn duly maneuvered Friendship 7 into a 14-degree, nose-up attitude. At 2:20 p.m. EST, the first retrorocket fired, causing a dramatic braking effect on the capsule and making him feel momentarily as if he was flying backwards, towards Hawaii. The second and third retrorocket firings came at five-second intervals, slowing the capsule sufficiently to drop it out of orbit. Once again, Schirra repeated, “Keep your retro pack on until you pass Texas.”

The tension at Mission Control was palpable. “I looked around the room,” wrote Procedures Officer Gene Kranz in his autobiography, Failure is Not an Option, “and saw faces drained of blood. John Glenn’s life was in peril.”

Throughout the early stages of re-entry, Glenn and Schirra chatted like a pair of tourists exchanging travel notes, as Friendship 7 came within sight of El Centro and the Imperial Valley, followed by southern California’s Salton Sea. Then, as he passed over Corpus Christi, Glenn was told again, with evident urgency, to “leave the retro package on through the entire re-entry”.

This meant that he would have to override the 0.05 G switch—which sensed atmospheric resistance and started the capsule’s re-entry program—and manually retract the periscope. Glancing at the on-board clock, his suspicions resurfaced that the reason for keeping the retro package on throughout re-entry was because the heat shield had indeed somehow become loosened.

Despite asking for Mercury Control’s reasons for wanting the package kept in place, he was told only that the decision was “the judgement of Cape Flight”. In Florida, Capcom Al Shepard gave Glenn as much information as he had. “We’re not sure whether or not your landing bag has deployed,” he said. “We feel it is possible to re-enter with the retro package on. We see no difficulty at this time with this type of re-entry.”

Although the package and its straps would eventually burn up as Friendship 7 plunged deeper into the atmosphere, Glenn assumed that, by keeping it on, the capsule might be protected for long enough until the thickening air naturally held the heat shield against Friendship 7’s base. Max Faget, the father of the Mercury spacecraft, agreed with the plan, but admitted that it posed its own risks: any unused solid fuel could explode when re-entry temperatures grew too high. And Flight Director Chris Kraft worried that the retro package could cause Friendship 7 to tumble uncontrollably.

As the main phase of re-entry got underway, Glenn switched Friendship 7 from manual to fly-by-wire control, placing the capsule in a slow spin to hold it onto its correct flight path. Just behind his back, the base of the spacecraft steadily heated to a maximum of 5,200 degrees Celsius (9,400 degrees Fahrenheit). Its ionized envelope of heat also blotted out communications, as Shepard’s voice in Glenn’s headset faded to nothing.

A thud reverberated through Friendship 7 as the retro package’s three metal straps melted, a fragment of which “fell against the window, clung for a moment and burned away”. Glenn would recount years later that he expected, as each second passed, to feel the heat on his back and along his spine, but continued working his procedures, as flaming bits of “something” streamed past the window. He had no idea if they were pieces of the retro package or, indeed, of the heat shield.

He was preoccupied for much of the re-entry with damping out the capsule’s oscillations with the hand controller, but had the brief opportunity to glance through the window and see the sky turn to a bright orange, which he described to the automatic tape recorder as “a real fireball outside”. Every few seconds, he attempted to contact Shepard, all the while working to keep Friendship 7 on the straight and narrow. At length, and by now through the worst of the re-entry heating, he heard the crackle of Shepard’s voice over his headset. The relief on the ground was audible.

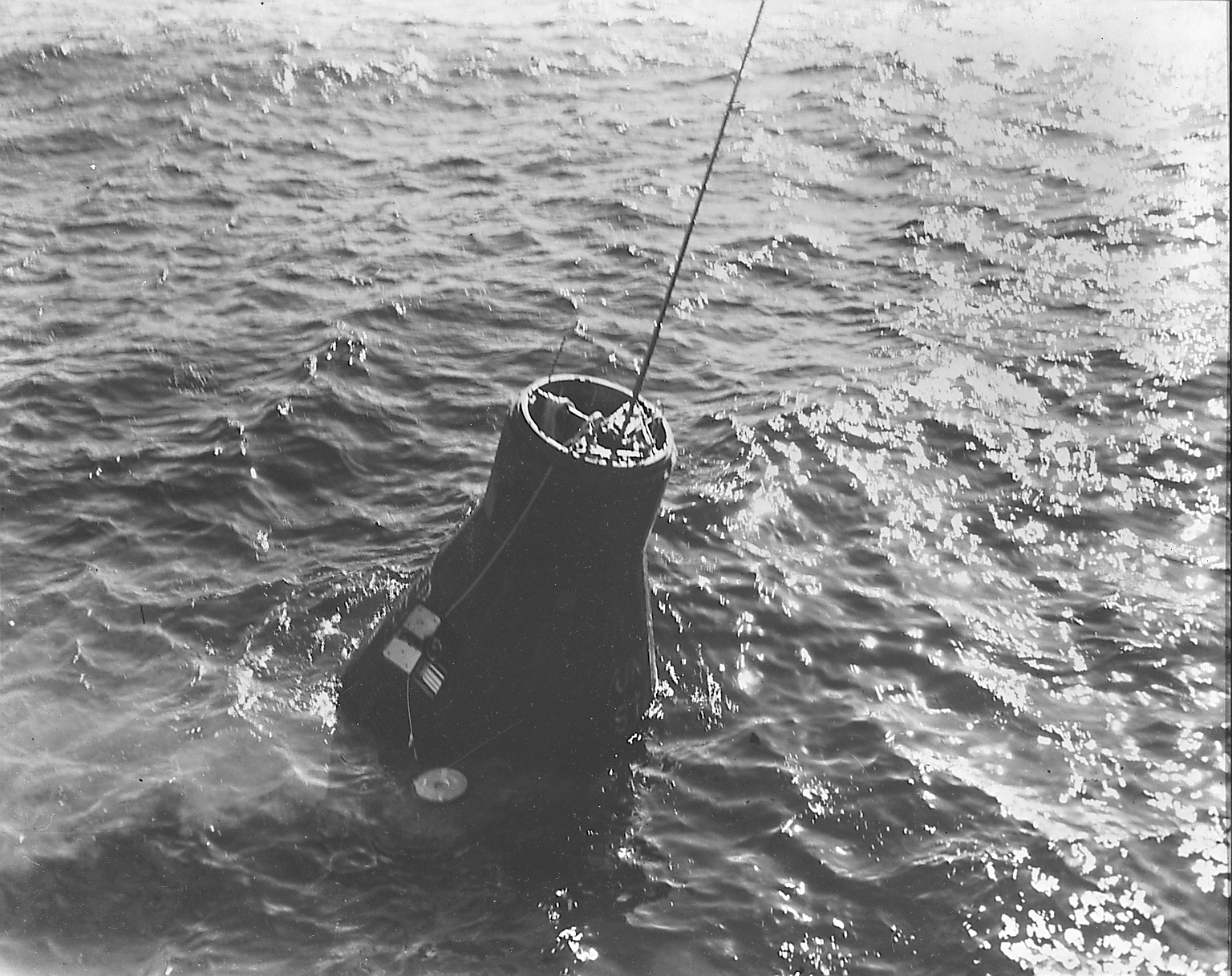

Descending at subsonic speeds, Glenn felt the capsule rocking wildly and, as he looked upwards, could see “the twisting corkscrew contrail of my path”. Five miles above the Atlantic, the stabilizing drogue chute deployed automatically, followed by the main canopy a few seconds later. Shortly before splashdown, Glenn flipped the landing bag deployment switch. As expected, it lit up. Green.

Subsequent investigation would discover that the rotary switch to be actuated by the heat shield deployment had a loose stem, which caused the electrical contact to break when the stem was moved up and down. This was believed to account for the false landing bag deployment signal.

Glenn splashed down with what he later described as “a good solid thump” at 2:43 p.m. EST. His landing co-ordinates were later given as 21 degrees 20 minutes North and 68 degrees 40 minutes West, some 200 miles (320 km) northwest of Puerto Rico. Seventeen minutes later, the destroyer USS Noa (codenamed “Steelhead”) drew alongside the capsule, followed by helicopters from the USS Randolph.

“I could hear gurgling sounds almost immediately,” Glenn said. “After it listed over to the right and then to the left, the capsule righted itself and I could find no traces of any leaks.” He released his straps and shoulder harness, removed his helmet and put up his neck dam. When the Noa arrived, he glanced through the window—coated with a smoky film from re-entry—and saw a deck full of sailors, so high in number that he asked the destroyer’s captain if anyone was actually running the ship.

According to physicians Robert Mulin and Gene McIver, Glenn was fatigued, sweating and dehydrated; his only water intake had been from the apple sauce pouch, although his urine collector was full. After drinking water and showering, he became more talkative. When asked by psychiatrist George Ruff if there had been any unusual activity during his mission, Glenn replied crisply: “No … just a normal day in space!”

2 Comments

2 Pings & Trackbacks

Pingback:Dragon Endeavour Splashes Down, Concludes Historic Ax-1 Mission - AmericaSpace

Pingback:“I Am Weightless”: Remembering Aurora 7, 60 Years On (Part 1) - AmericaSpace