Early on 14 May 1963, a hotshot pilot lay on his back in a tiny capsule, atop a converted ballistic missile, and steeled himself to be blasted into space. On Project Mercury’s final mission, Gordon Cooper would spend 34 hours in space, circle the globe 22 times, and establish NASA’s first real baseline of long-duration experience as the space agency and the nation prepared to land a man on the Moon before the end of the decade. To be fair, the flight would last barely a quarter as long as the Soviet Union’s four-day Vostok 3 mission a year earlier, but for NASA it would mark an important step forward. Yet there were many senior managers who doubted Cooper was right for the job. Two days earlier, he had buzzed the administration building at Cape Canaveral in his F-106 jet, sparking a flurry of frantic emergency calls and maddening Project Mercury Operations Director Walt Williams to the extent that he almost grounded Cooper in favor of his backup, Al Shepard. Cooper had much ground to make up in order to restore faith in his abilities.

On launch morning, Cooper breakfasted with Shepard. Only hours earlier, Shepard had convinced himself that the mission was his for the taking. He could not believe that Cooper could possibly be so rash as to buzz the very building in which his bosses were holding a meeting and was frustrated at the lost opportunity to fly himself, to the extent that he planned a somewhat mean-spirited joke. Press spokesman John “Shorty” Powers had arrived early that morning with two cameramen, who would shoot behind-the-scenes footage of Cooper as he prepared for launch. To their shock, they discovered that none of the overhead lights were working, nor were the electrical sockets. Someone had cut the wires, removed every light bulb, inserted thick tape into the sockets, and replaced the bulbs. No one pointed any fingers, but Powers recognized Shepard’s grin. It was typical of him, said Powers, “when he has a mouse under his hat.”

Another gift from Shepard awaited Cooper when he boarded the spacecraft he had named “Faith 7” at 6:36 a.m. EDT: a small suction-cup pump on the seat, labeled Remove Before Flight, in honor of the new urine-collection device. (Cooper would become the first Mercury astronaut to urinate in a manner other than “in his suit”). At this stage, the only indication of doubt that the mission would fly came from meteorologist Ernest Amman, although the trouble increased when a radar at the secondary control center in Bermuda malfunctioned. Next, at 8 a.m. EDT, with an hour remaining in the countdown, a diesel engine stubbornly refused to work. It was supposed to move the gantry away from the Atlas rocket, and two hours were wasted trying to fix a fouled fuel injector pump. The countdown resumed around midday and the gantry was successfully retracted, but a computer converter failed at the Bermuda station and the launch attempt had to be scrubbed.

Despite having spent six hours on his back, Gordon Cooper was upbeat and managed to summon a wry grin when he was extracted from Faith 7. “I was just getting to the real fun part,” he said. “It was a very real simulation!” As the astronaut spent the afternoon fishing, technicians readied the Atlas and the spacecraft for another attempt, early on 15 May.

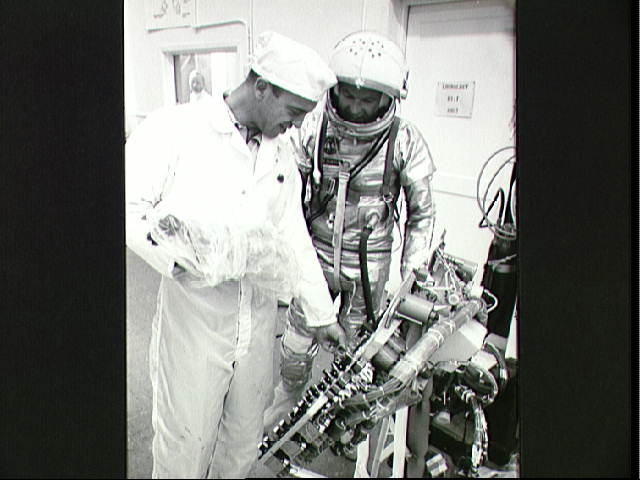

Arriving at the capsule for the second time, he saluted McDonnell pad leader Guenter Wendt with mock formality, reporting in as “Private Fifth Class Cooper”, to which the German pad “fuehrer” responded in kind. The roots of the joke came two years earlier, when Cooper stood in for Alan Shepard in a practice countdown session. His mock terror—begging Wendt not to make him climb aboard the primed rocket—had so annoyed a number of NASA managers that a couple even threatened to bust him to Private Fifth Class. Ironically, Cooper and Wendt liked the idea and ran with it.

Despite a problem with the Atlas’ guidance equipment, which necessitated a brief hold, the countdown marched crisply on this second attempt; so crisply, in fact, that Cooper fell asleep. It took fellow astronaut Wally Schirra several efforts to bellow his name over the communications link to awaken him. Then, with just 19 seconds to go, another halt was called in order to allow launch controllers to ascertain that the rocket’s systems had properly assumed their automatic sequence. Shortly after 8 a.m. on 15 May 1963, America’s sixth man in space thundered off the pad in what Cooper would later describe as “a smooth, but definite push”. Within minutes, Faith 7 was inserted into an orbit so good that its heading was 0.0002 degrees from perfect and its velocity “right on the money” at 17,550 mph (28,240 km/h). “Smack-dab in the middle of the plot,” an admiring Schirra told him.

So rapid was Cooper’s passage across the Atlantic Ocean that he expressed astonishment when called by the tracking stations in the Canaries and Kano in Nigeria. The first day of the mission went extraordinarily well—at one stage, the astronaut’s heart rate surged during a sleep period, suggesting that he was experiencing an exciting dream—and he moved swiftly through his many tasks. Cooper’s use of the cabin’s oxygen supply was so efficient that Shepard jokingly asked him to “stop holding your breath.” The astronaut responded that—as the only non-smoker amongst the Mercury Seven—his lungs were in better shape than those of his comrades. If his oxygen usage was minimal, so too was his fuel expenditure, to such an extent that controllers nicknamed him “The Miser”.

One of Cooper’s most important experiments was the deployment of a six-inch (15-cm) sphere, instrumented with xenon strobe lights, part of an effort to track a flashing beacon in space. Three hours after launch, the astronaut clicked a squib switch and felt the experiment separate from Faith 7, but he was only able to see it very occasionally, at orbital sunset, pulsing in the darkness. Another experiment involved the release of a 30-inch (76-cm) Mylar balloon, painted fluorescent orange. Nine hours into the mission, Cooper set cameras, attitude, and switches to deploy the balloon, but it refused to move. Another attempt was also fruitless. The intent was for the balloon to inflate with nitrogen and extend on a 100-foot (30-meter) tether, after which a strain gauge would measure differences in “pull” at Faith 7’s 168-mile (270 km) apogee and 99-mile (160 km) perigee. Sadly, the cause of the balloon’s failure was never ascertained.

Evaluating an astronaut’s ability to make observations from space achieved more success when Cooper spotted a 3-million-candlepower xenon light at Bloemfontein in South Africa. He also made detailed notes as he flew over cities, large oil refineries, roads, rivers, and small villages, and even saw smoke twirling from the chimneys of Himalayan houses. Lighting conditions had to be appropriate for such observations, but in the wake of the mission Cooper’s claims were disputed, until two visibility researchers from the University of California at San Diego verified that in one instance the astronaut had seen a Border Patrol vehicle’s dust cloud, kicked up on a dirt road near El Centro on the U.S.-Mexican border. The researchers argued that the vehicle and dust cloud were more visible from Cooper’s vantage point than from the road itself.

Ten hours after launch, the astronaut was advised that he had exceeded Wally Schirra’s endurance record for the longest American manned mission and that his orbital parameters were good enough for at least 17 circuits of the globe. The phenomenal speed of his flight path was amply illustrated when he spoke to fellow astronaut John Glenn, based on the Coastal Sentry tracking ship, near Kyushu, Japan, then swept south-eastwards, over the empty Pacific Ocean, to speak to a controller near Pitcairn Island, more than 6,800 miles (11,000 km) distant, just ten minutes later.

Sleeping in space was virtually impossible, so spectacular was the view. As Cooper passed over South America, then Africa, northern India, and into Tibet, the photographic opportunities were priceless. Using the direction of chimney smoke from the Himalayan houses, he was even able to make a few rudimentary estimates about his velocity and the ground winds. Despite the difficulty, he pulled Faith 7’s window shades around 13 hours after launch to catch some sleep. He dozed intermittently, but found himself having to anchor his thumbs into his helmet restraint strap to keep his arms from floating freely. Every so often, he would lift the shade to take photographs or make status reports or curse quietly to himself when his body-heat exchanger crept too high or too low.

With the exception of niggling glitches, everything seemed to be going well. Cooper’s oxygen supply was plentiful and his fuel gauges for both automatic and manual tanks looked good. During a brief spell of quiet time, he paused for a short prayer. He thanked God for the privileged opportunity to fly the mission, for being in space, and for seeing such wondrous sights. That prayer marked the beginning of Faith 7’s troubles. Early on his 19th orbit, around 30 hours after launch, he was over the western Pacific Ocean and out of radio contact with the ground, when his attention was arrested by the eerie green glow of one of his instrument panel lights. It was the “0.05 G” indicator, and it should normally have illuminated after retrofire, as Faith 7 commenced its descent from orbit. Moreover, it should have been quickly followed by the autopilot placing the capsule into a slow roll.

Had Cooper inadvertently “slipped” out of orbit?

This suspicion was quickly refuted by orbital data from the ground, which suggested either that the indicator was at fault or that the autopilot’s re-entry circuitry had been tripped out of its normal sequence. An orbit later, Cooper was advised to switch to autopilot and Faith 7 began a slow roll. This presented its own issues. For proper flight, the autopilot had to perform other functions before retrofire, and, since each function was sequentially linked, Mission Control knew that several earlier steps had not been executed. This meant that the astronaut might be forced to control those steps by hand. Worse was to come. On his 20th orbit, Cooper lost all attitude readings and, a revolution later, one of three power inverters went dead. He tried to switch to a second inverter, but it would not respond. The third was needed to run cooling equipment during re-entry, so the astronaut was now left with an autopilot devoid of electrical power.

On the ground, the options centred on bringing Cooper home on batteries alone. The astronaut could not rely on his gyroscope or clock to properly position Faith 7 for re-entry, since both depended on electrical power, and he watched with dismay as carbon dioxide levels began to rise both in the cabin and within his space suit. In true Right Stuff fashion, his comment over the radio to fellow astronaut Scott Carpenter was nonchalant: “Things are beginning to stack up a little!”

At length, on his 22nd orbit, Cooper made his way smoothly through the pre-retrofire checklist, steadying Faith 7 with his hand controller and lining up a horizontal mark on his window with Earth’s horizon; this dipped the capsule’s nose to the desired 34-degree angle. Next, he lined up a vertical mark with pre-determined stars to acquire his correct heading and astronaut John Glenn counted him down to retrofire. Cooper hit the button once—receiving no light signals, due to his electrical system problems—and verified that he could feel the punch of the three small engines igniting behind him. During the descent from orbit, he periodically damped out unwanted motions with his hand controller and manually deployed both his drogue and main parachutes. Faith 7 hit the Pacific, about 80 miles (130 km) southeast of Midway Island, within sight of the recovery ship USS Kearsarge.

The capsule floundered for an instant, then righted itself. Cooper’s 34-hour mission had concluded just as each of the Mercury Seven would have wanted: with a pilot in full control of his craft. As for Walt Williams, the disgruntled Project Mercury Operations Director, who had tried to have Cooper removed from Faith 7, it was a case of having been proved wrong. When the pair met at Cape Canaveral, Williams warmly shook Cooper’s hand. “Gordo,” he said, “you were the right man for the mission!”

I believe that Cooper’s attitude and demeanor prevented him from walking on the Moon even though he did serve on the Apollo 14 backup crew. Sad.

The headline in the Syracuse Herald Journal read: “Cooper Super on 22-Looper.” How’s that for a headline?

This guy was the real world Jebediah Kerman!