More than 60 years ago, a pair of astronauts prepared for America’s third Earth-orbital space mission. Wally Schirra and Gordo Cooper—prime and backup crewmen for Mercury-Atlas-8 (MA-8), a flight Schirra had nicknamed “Sigma-7” on account of its engineering focus—were training to launch atop a giant Atlas rocket and spend up to nine hours and six orbits in space.

But before either man could be cleared to fly, they had to make it past the doctors. And an all-powerful figure that they encountered each day was the astronauts’ nurse, the formidable Dee O’Hara.

Urine samples were part and parcel of their medical regimen and Schirra and Cooper trusted O’Hara implicitly to take theirs each day. One morning in September 1962, the nurse arrived at her office to be greeted by the latest “specimens” from Schirra and Cooper.

But whenever Schirra was around, a practical joke sat not far behind.

On this occasion, the astronauts left O’Hara a huge bottle in the middle of her desk, filled with warm water, colored with iodine and foamed-up with laundry soap. For good measure, Schirra tagged the bottle’s delivery time in Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), playfully added a handful of lollipops and retreated to await the nurse’s arrival at work.

O’Hara walked in, took a horrified look at the enormous specimen bottle and burst out laughing. Schirra later dedicated a photograph of the nurse, clutching the bottle, and inscribed it with a simple legend: Gotcha. But Schirra’s Sigma-7 mission, which flew on this day in 1962, would be filled with great drama, excitement…and a few gotchas of its own.

He and Cooper had been named as prime and backup crewmen the previous July and the flight was jam-packed with engineering tasks, emphasizing spacecraft systems and management of hydrogen peroxide propellant usage for attitude-control and careful conservation of electrical power. One of few scientific tasks would be an attempt to observe a ground-based xenon floodlight in Durban, South Africa, which would glimmer at 140 million candlepower, and a one-million-candlepower quartet of flares at Woomera, Australia. A few other terrestrial and weather observations were planned, but on the whole Sigma-7 was a pure engineering test flight.

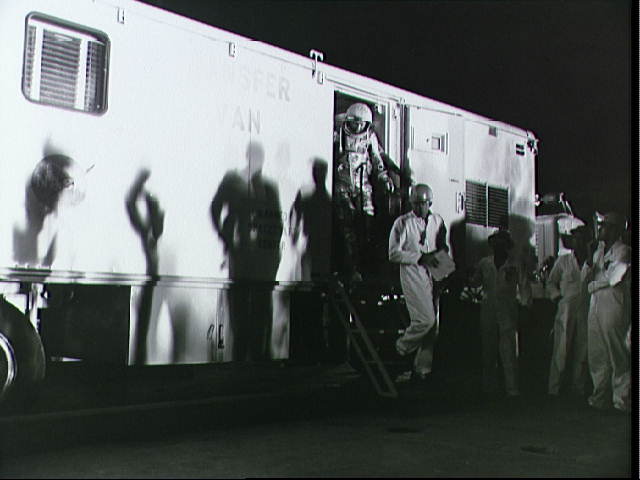

Early on 3 October, Schirra was awakened in the quarters of Cape Canaveral’s Hangar S by Air Force flight surgeon Howie Minners. He showered, dressed and ate the traditional breakfast of steak and eggs.

Another item also took pride of place on the breakfast menu. The previous evening, Schirra and fellow astronaut Deke Slayton had gone fishing. The Cape had earned renown for its excellent surf fishing, especially in the spring and autumn, and the two astronauts hooked several bluefish.

They were “in the five-pound range,” wrote Schirra in his autobiography, Schirra’s Space, “but they fought free by severing our leaders with their razor-sharp teeth. I managed to land one by slinging it on the beach and pouncing on it before it could wriggle back to the surf”. The bluefish, it seemed, was not the only individual with a shock in store. The two astronauts were aware of a Thor-Delta rocket—carrying NASA’s Explorer 14 satellite—situated on nearby Pad 17, but they did not know how close it was to launch.

“It wasn’t until we heard a roar that we realized the Thor-Delta was lifting-off,” wrote Schirra. “We were looking right up the tailpipe of its monster engine and we knew right away that we were in the danger zone. Had there been an abort, it would have been a bad day for Mercury, with the chief astronaut and the pilot of MA-8 incinerated like the legendary rattlesnakes.”

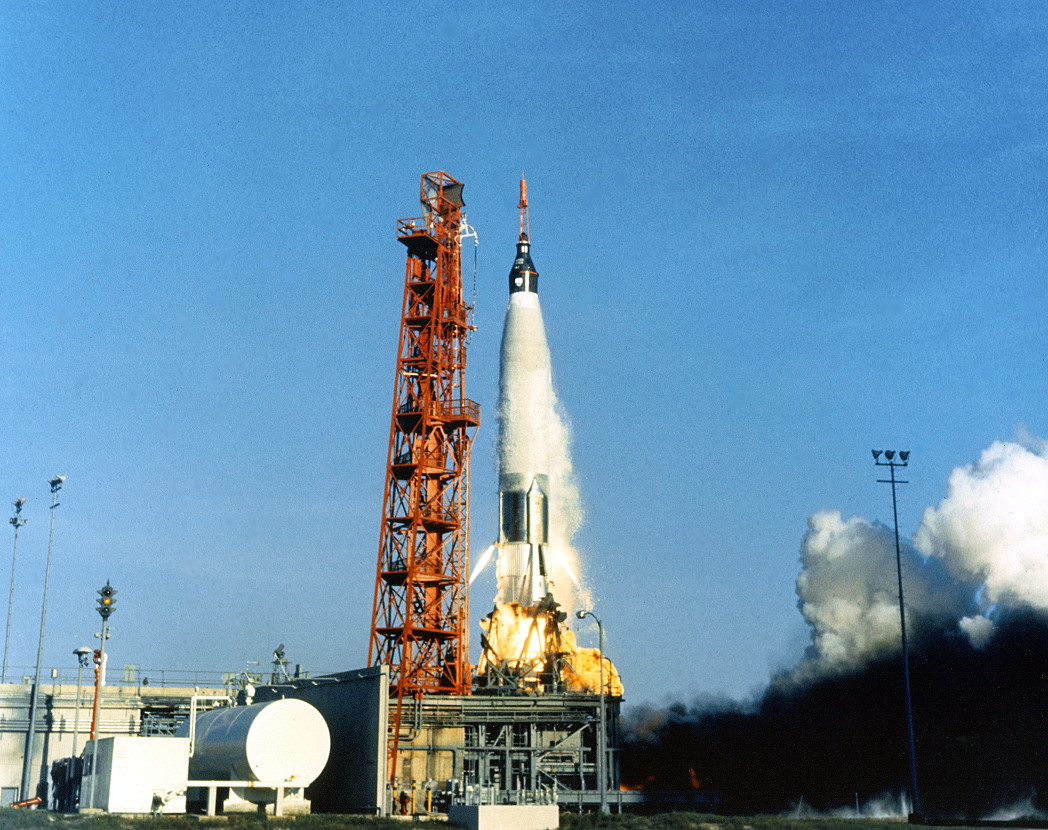

America’s third manned orbital mission took flight at 7:15 a.m. Eastern Time, with Schirra describing the exhilaration of ascent as “disappointingly short”; a nominal ride, despite a greater-than-expected roll-rate of the Atlas rocket. Three minutes into ascent, Slayton—seated at the blockhouse console—radioed cryptically: “Are you a turtle, today?”

The roots of the strange question were explained by Schirra. He told the tale of a good and noble man, sickened by the vulgar minds of those around him and driven to despair over whether he will meet someone of his own intellect.

At length, he retreated, turtle-like, into a protective shell and found his only respite in the consumption of alcohol (“for purely medicinal purposes, of course”). Over time, he sought out other like-minded individuals to join his drinking fraternity, dubbed the ‘Ancient and Honourable Order of Turtles’.

However, he needed money and gambled his most prized possession—a donkey—on a horse running at long odds at the local track. Fortunately, he won the bet and kept the donkey.

To commemorate his triumph, all future members of the fraternity, when asked “Are you a turtle?” were expected to reply, without hesitating, “You bet your sweet ass I am!” Failure to do so would consign the victim to buy drinks for everyone close enough to have overheard the question.

Unfortunately for Schirra, the question had been asked over a “hot-mike” and, if he did not answer correctly, the number of people “within earshot” demanding alcoholic sustenance could run into hundreds! On the other hand, even though “ass” in this context referred innocently to the donkey, responding correctly to Slayton’s question over the open mike could have led to misunderstanding and embarrassment.

Schirra was in a quandary. Then, he told Slayton “Going to VOX record only” and announced the correct response into Sigma 7’s voice recorder. Schirra was spared the need to buy drinks, but Slayton scored his own launch-day ‘gotcha’ and put his friend briefly in the hot seat.

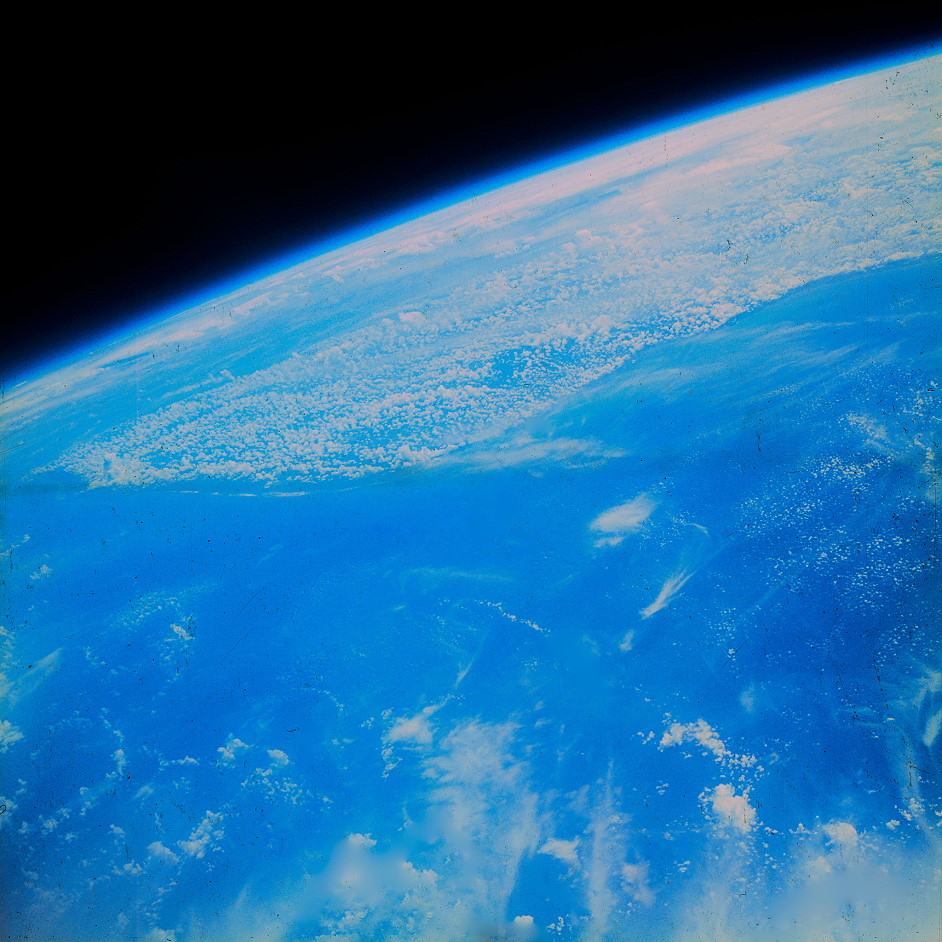

With Sigma-7 safely in orbit, Project Mercury was drawing to a close and the mission was tasked to be the most complex flight so far. Operating at an altitude of 160 miles (260 kilometers), higher than any previous U.S. astronaut, Schirra set briskly to work evaluating his ship’s systems.

“With my eyes fixed on the control panel, studiously ignoring the view, I began a slow, four degrees per second, cartwheel,” he wrote in Schirra’s Space. “Once in the correct orbital position, I checked my fuel. I had used less than half a pound of hydrogen peroxide. The thruster jets worked perfectly. They responded crisply to my touch and shut off without any residual motion. I was able to make tiny, single-pulse spurts—the “micro-mouse farts”—to assume an exact position.”

During this time, Schirra oriented his capsule to get a better view of the Atlas rocket as it tumbled away. He concluded that his efforts demonstrated that rendezvous in space (a crucial requirement for reaching and landing on the Moon) was possible in a practical sense. The manual system, on the other, seemed somewhat “sloppy”, with a tendency to ‘overshoot’, and Schirra switched next to the third control mode: the autopilot, which he disparagingly called “chimp mode”.

At around this time, his pressure suit began overheating. The suit had been one of Schirra’s areas of responsibility during training and he would comment later on the seriousness of the situation; in fact, Flight Director Chris Kraft even considered terminating the mission after just one orbit. Before launch, Schirra had developed his own technique should overheating occur: he would inject cool water very slowly into the system, advance the temperature knob by half a mark at a time, then wait for ten minutes. He did not want to rush the water, lest the heat exchanger freeze.

It worked. By the end of his first orbit, the temperature had dropped to 32 degrees Celsius (89 degrees Fahrenheit), which Schirra considered “hot, but not unbearable”. Flight surgeon Chuck Berry advised Kraft to press on with a second orbit and the news was relayed to Schirra by Capcom Scott Carpenter, based in Guaymas in Mexico.

Schirra was pleased, not only with the prospect of a full-length mission, but the realization that the problem was “solved through no great amount of ingenuity, but the point was it was solved by a human”. The need to fly people into space had been vindicated. After the mission, Schirra would receive a plaque, signed by Frank Samonski of Sigma-7’s environmental control system team and emblazoned with the legend that they had ‘sweated more than you did during the first orbit of MA-8’. Affixed to the plaque was the valve used by Schirra to control the water flow to his suit.

Later, as Sigma-7 began its third orbit, Schirra entered a period of drifting flight, during which time he undertook a psychomotor experiment: closing his eyes and touching certain dials on the control panel. “I missed only three out of nine,” he wrote later, “concluding that my sense of direction and distance had not been impaired by weightlessness.”

Repowering his ship, high above the Indian Ocean, Schirra switched back to fly-by-wire and successfully fixed his attitude using the Moon in the window as a reference point. Aware that flight controllers had been closely monitoring his fuel consumption, he expressed a hearty “Hallelujah!” when Capcom Virgil “Gus” Grissom, situated at the Kauai station in Hawaii, radioed approval to fly a full six orbits.

On the fifth orbit, busily working through his pre-retrofire checks, Schirra was infuriated to hear a voice interrupt from Quito in Ecuador. “We had what we called a ‘mini-track’ there,” he wrote, “a miniature tracking station, and it wasn’t supposed to come on the air except in an emergency.”

The speaker asked the astronaut if he had any words for the people of South America. Schirra, irritated, wished them “Buenos dias, you all”. After splashdown, he would receive a handful of telegrams, complaining of his brusqueness. “But there was one,” he wrote, “I treasured from a U.S. diplomat in Ecuador. He said in effect that Schirra had proved his devotion to the people of Latin America by wishing them a good day.”

Preparations for re-entry commenced over Africa, when Schirra transitioned to fly-by-wire control to orient Sigma 7 using celestial reference points, then switched to the autopilot to ensure that it operated satisfactorily in this mode. “The flight plan called for me to position the spacecraft using manual controls,” he wrote, “then switch to automatic for retrofire, because the power of the big thrusters offsets the unbalancing force of the retrorockets. The retrorockets exert their force through the centre of the spacecraft, so they don’t kick it off course.”

In Schirra’s case, however, the retrorockets of his “sweet little bird” fired perfectly and in sequence under automatic conditions at 4:07 p.m. Eastern Time, a little under nine hours since launch. Shortly thereafter, he switched the capsule to fly-by-wire, although Sigma-7 was “steady as a rock”, with so much fuel remaining in its automatic and manual supplies that he had to “dump” it during re-entry.

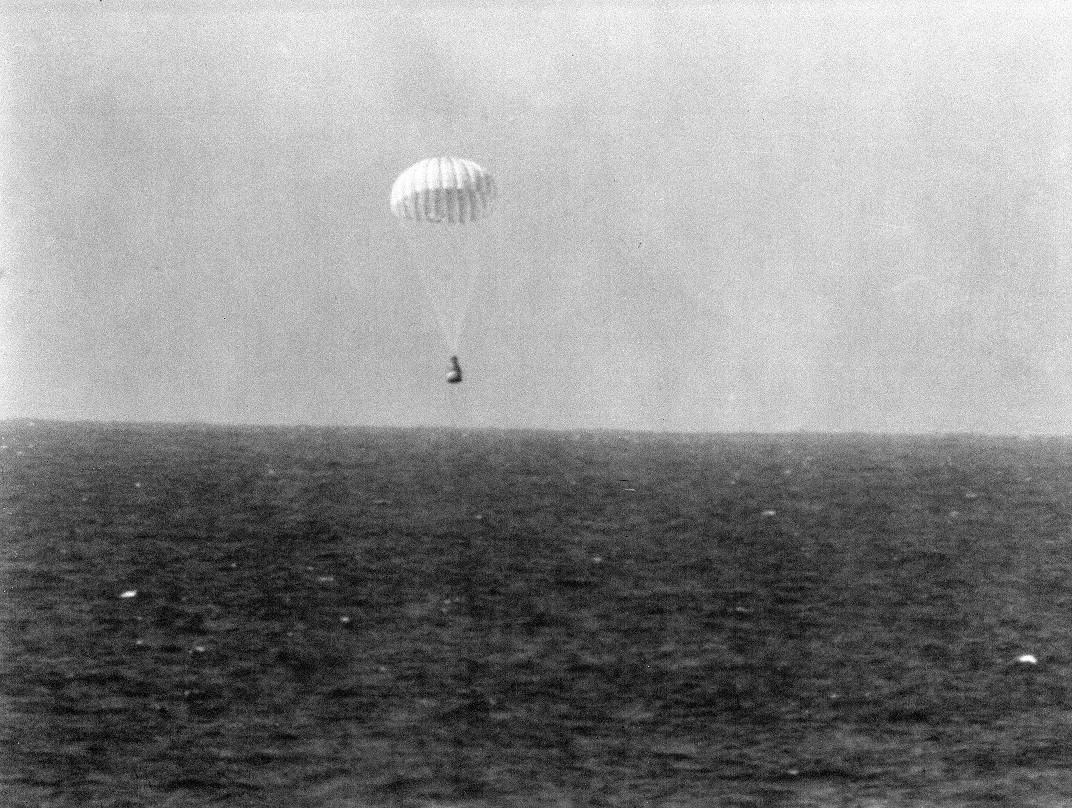

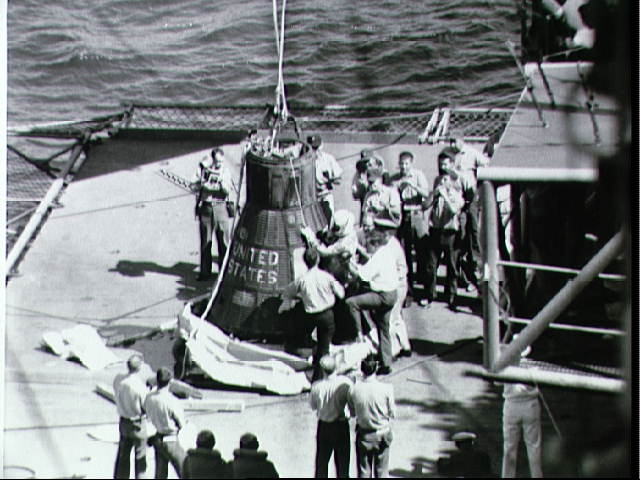

Minor adjustments were needed to damp out wobbles after the jettison of the retrorocket package, but the descent was as ‘textbook’ as the mission itself. Schirra manually deployed the drogue and main chutes, his elation evident in his words to Grissom, and splashed down just four miles from the USS Kearsarge at 4:28:22 p.m. Within minutes, wrote Schirra, “a whaleboat was alongside and the underwater team had the flotation collar in place”. Stepping aboard destroyer’s deck, he noted that it was barely ten hours—and six full orbits—since his launch from Florida.

Another surprise awaited him in the admiral’s quarters: an oversized urine-collection bottle, sent specially by the astronauts’ canny nurse, Dee O’Hara. Almost identical to the one that Schirra and Cooper had mischievously dumped on her desk a few weeks earlier, it concluded the perfect mission with the perfect Gotcha.