Four hundred miles (640 km) to the north of the Moon’s equator lies a place called Hadley: a small patch of Mare Imbrium at the base of the Apennine Mountains—some of which rise to 4,000 feet (1,200 meters)—and a 25-mile (40-km) meandering gorge, known as Hadley Rille. In July 1971, Apollo 15 Commander Dave Scott and Lunar Module Pilot (LMP) Jim Irwin expertly negotiated these forbidding landmarks in the Lunar Module (LM) Falcon and set down in one of the most visually spectacular regions ever visited by mankind. They brought back a scientific yield which revealed more about the Moon’s origin and evolution than ever before. Forty-five years ago, this week, in July-August 1971, Apollo 15 conducted one of the most brilliant missions ever undertaken in the annals of space science.

It is therefore ironic that this triumph actually arose from the ashes of defeat. Original plans called for four “H-series” lunar landing missions—Apollo 12 through 15—which would each spend 33 hours on the Moon and feature two periods of Extravehicular Activity (EVA). The final missions, belonging to the “J-series,” would perform longer missions, spend 70 hours on the surface, make three EVAs, and utilize a battery-powered rover. In September 1970, everything changed when NASA canceled one H-series mission and one J-series mission; as a result, the schedule shifted to maximize the scientific harvest from the remaining flights. Apollo 15 was upgraded to the ambitious J-series, and it was this decision which altered its scope and its place in history.

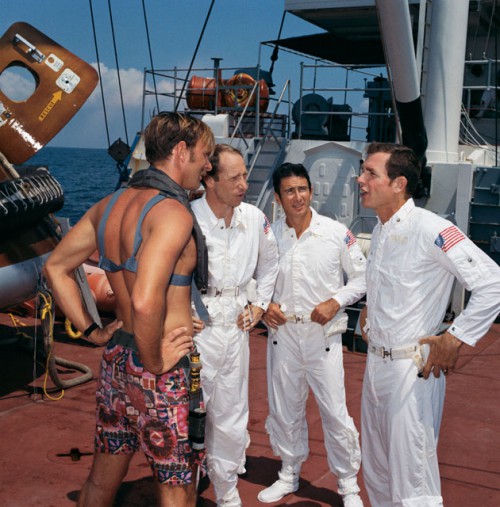

The countdown on 26 July 1971 was near-perfect. In fact, Launch Director Walter Kapryan described it as “the most nominal countdown that we have ever had.” The astronauts—Scott, Irwin, and Command Module Pilot (CMP) Al Worden—were awakened early that morning, breakfasted on steak and eggs, caught a brief nap as they were being suited-up, and were helped into their couches aboard the Apollo 15 Command and Service Module (CSM), Endeavour, at around 7 a.m. EDT. The clang of the hatch shutting them in startled Irwin. “I think that is when the reality of the situation hit me,” he wrote in his memoir, To Rule the Night. “I realized I was cut off from the world. This was the moment I had been waiting for. It wouldn’t be long now.”

From his couch on the right-hand side of the spacecraft, Irwin had little to do and had some brief respite to reflect on his life, consider the enormity of the mission ahead of him, and, more than anything, give himself over to an air of anticipation and expectancy as he waited for the Saturn V to boost them toward the Moon.

Fifteen minutes before launch, they felt and heard the unearthly clanking of Pad 39A’s access arm moving away from the spacecraft, then beheld the stunning blaze of sunlight through the command module’s only uncovered porthole. As the countdown entered its final seconds, the glare of the Sun was so intense that Scott had to shield his eyes just to read the instrument panel in front of him. Precisely on time, at 9:34 a.m. EDT, the five F-1 engines of the Saturn V’s first stage came to life with a muffled roar. “You just hang there,” Irwin wrote. “Then you sense a little motion, a little vibration and you start to move. Once you realize you are moving, there is a complete release of tensions. Slowly, slowly, then faster and faster; you feel all that power underneath you.”

Four days later, after crossing 240,000 miles (370,000 km), Apollo 15 slipped into orbit around the Moon. Scott and Irwin, aboard Falcon, undocked from Worden in Endeavour and began their descent to the surface. Moving in a sweeping arc toward the Apennines, at an altitude of four miles (6.4 km), Scott began to discern the long, meandering channel of Hadley Rille. The terrain was less sharply defined that he had anticipated on the basis of simulations, yet he was able to find four familiar craters: Matthew, Mark, Luke, and Index—the latter of which they had used in landmark sightings from orbit. (The name “Index” was deliberately chosen instead of “John” in order to stave off complaints from the atheist Madalyn Murray O’Hair, whose criticism of overtly religious symbolic gestures on missions had scalded NASA during Apollo 8 in December 1968.)

Dropping through a gap in the lunar mountains, Scott had the surreal feeling that he was “floating” with strange slowness toward his landing site. “No amount of simulation training,” he wrote in his memoir, Two Sides of the Moon, “had been able to replicate the view we saw out of our windows as we passed by the steep slopes of the majestic lunar Apennine Mountains.” In the simulator, they “flew” a television camera toward a small, relatively flat patch of plaster-of-Paris; now they drifted between the astonishing 16,400-foot (5,000-meter) peaks of the mountains to both their left and right as they threaded their way toward Hadley. “It made us feel,” he added, “almost as if we should pull our feet up to prevent scraping them along the top of the range.”

As they continued to descend, Falcon’s computer transitioned to “Program 66,” enabling Scott to fly manually. “Dave didn’t want me looking at the surface at all,” Irwin wrote. “He wanted me to concentrate on the information on the computer and other instruments. He wanted to be certain that he had instant information relayed to him. He was going to pick out the landmarks. But Dave couldn’t identify the landmarks; the features on the real surface didn’t look like the ones we had trained with.” Scott could see Hadley Rille and used that long gouge as his marker, but was worried that they might land “long” and far to the south of their intended spot. This fear was confirmed by Capcom Ed Mitchell; they were, indeed, 0.5 miles (0.8 km) or more south of track. Scott knew that, even with the lunar rover, this might impair the effectiveness of their explorations. During those final moments, he clicked his hand controller 18 times, forward and to the side, adjusting their trajectory to bring Falcon back onto its prescribed path.

Those seconds were so unreal—the clarity of the scene, the weird behavior of the lunar dust, the strange, almost-unpowered sense of drifting like a snowflake through the majesty of the lunar mountains—that Irwin mentally convinced himself that he was still in the simulator back at the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC) in Houston, Texas. If he had admitted to himself that this was for real, he felt that he would have been just too excited to do his job properly. Yet if this was a simulation, it was one of the smoothest that he had ever flown. They were very close to the surface now and lunar dust obscured the landing site entirely, like a thick fog. It was only Irwin’s call that the blue Contact Light had illuminated which finally convinced them that they had touched down.

The time was 6:16 p.m. EDT on 30 July 1971 and, with a firm thud, the seventh and eighth men from Earth reached the surface of the Moon. “Okay, Houston,” radioed Scott, “the Falcon is on the Plain at Hadley!” His reference to the landing site as a “plain” paid due tribute to Scott’s alma mater, the Military Academy at West Point, whose parade ground was also nicknamed “The Plain.”

What did cause concern was that Falcon had come down on uneven ground and one of its rear footpads had planted itself inside a small crater. (Mission Control would later call their lunar module “The Leaning Tower of Pisa,” an epithet which Scott did not appreciate!) Irwin remembered the landing as the hardest he had ever been involved in; “a tremendous impact with a pitching and rolling motion. Everything rocked around and I thought all the gear was going to fall off. I was sure something was broken and we might have to go into one of those abort situations. If you pass 45 degrees and are still moving, you have to abort. We just froze in position as we waited for the ground to look at our systems. They had to tell us whether we had a STAY condition.” With some relief, 77 seconds after touchdown, Mission Control radioed their approval for Scott and Irwin to STAY.

“The excitement was overwhelming,” Irwin wrote, “but now I could let myself believe it.” They had set down in a beautiful valley, with the mountains of the Apennines on three sides of them and Hadley Rille about a mile (1.6 km) to the west. In his mind, it conjured up boyhood memories of the mountains of Colorado, high above the tree line; yet there was something else about it, too. Irwin was certainly one of the more religious men in the astronaut corps, and he would later make little secret of the fact that he acutely sensed the presence of a supreme being on the Moon. This sensation reached its sharpest whenever he looked up at Earth in the black sky. “That beautiful, warm living object looked so fragile, so delicate, that if you touched it with a finger it would crumble and fall apart,” he wrote. “Seeing this has to change a man, has to make a man appreciate the creation of God and the love of God.” This profound experience would remain with Irwin and guide his steps for the rest of his life.

One of the skills that Scott learned during his geology training was the need to gain a visual perspective of the site that he was about to explore. With this in mind, he requested mission planners to schedule a Stand-Up EVA (SEVA) a couple of hours after touchdown, in which he would stand on the ascent engine cover, poke his helmeted head through Falcon’s top hatch, and photograph his surroundings. At first, Director of Flight Crew Operations Deke Slayton opposed the idea, on the grounds that it would waste valuable oxygen, but Scott fiercely argued his case and eventually won approval. To conduct this half-hour SEVA, Scott pulled a balaclava-like visor over his clear bubble helmet, clambered onto the ascent engine cover, and removed the top hatch. It was, he wrote, “rather as if I was in the conning tower of a submarine or the turret of a tank.”

Meanwhile, Irwin shaded the instrument panel from the unfiltered lunar sunlight and arranged Scott’s oxygen hoses and communications cables to allow him to stand upright. “He offered me a chance to look out,” Irwin wrote, “but my umbilicals weren’t long enough and I didn’t want to take the time to rearrange them.” In the weak gravity, Scott found that he could easily support himself in the hatch on his elbows … and saw the stunning brown-tan Apennines. Irwin passed up a bearing indicator and a large orientation map, which Scott used to shoot a couple of dozen interconnected stereo pictures of the landing site now officially known as “Hadley Base.”

As his eyes adapted, and his mind connected it with months spent examining Lunar Orbiter geology maps, Scott began reeling off the landmarks. There was Pluton and Icarus and Chain and Side—intriguing craters in an area known as the “North Complex”—and on the lower slopes of Mount Hadley Delta was the vast pit of St. George Crater. One prominent, rocky landmark which they had dubbed “Silver Spur” in honor of their geology professor, Lee Silver, showed clear evidence of stratigraphy in its flanks.

“The SEVA was a marvelous and useful experience, for a lot of reasons,” Scott later explained for the Apollo Lunar Surface Journal. “One of our problems at Hadley was that the resolution of the Lunar Orbiter photography was only 60 feet (18 meters), so they couldn’t prepare a detailed map. The maps we had were best guesses and we had the radar people tell us before the flight that there were boulder fields … all over the base of Hadley Delta. So another reason for the stand-up EVA was to look and see if we could drive the rover, because if there were boulder fields down there, and nobody could prove there were no boulder fields, it changed the whole picture.”

The view set his mind at ease, appearing totally unhostile and contradicting his pre-flight fears. The “trafficability,” as Scott put it, would be excellent. Back inside Falcon, acutely aware that they were the only inhabitants of Earth ever to visit this barren place, the astronauts removed their suits and set about preparing their evening meal and getting ready for sleep. “Tomato soup was big on the menu, as I recall,” Scott wrote in Two Sides of the Moon. “There was no hot-water supply in the LM, as there was in the command module, so all our meals on the lunar surface were served cold and we soon discovered that there was not really enough to eat, either.”

Scott and Irwin later recommended that more food be carried on Apollo 16 and 17, for walking on the Moon required huge reserves of energy and stamina and was hungry work. Irwin, too, remembered Apollo 15’s staple of soups. “Eating them required some acrobatics,” he wrote. “They were … in plastic bags, but they had a Teflon seal that you had to peel off. We added water to the soups, then very carefully pulled the tab to open them up. If you opened them slowly, invariably the soup would start coming out in bubbles or blobs that would float all over the place. The trick was to open the bag fast, so that the viscosity or capillary action would encourage the soup to adhere to the plastic. The object was to take advantage of whatever adhesiveness the soup had.” When it had been thus “contained,” they could eat quite normally, with a spoon, directing it approximately toward their mouths.

Sleeping on the Moon, in their long johns, without the bulky space suits, was more comfortable in one-sixth gravity than it had been in pre-launch rehearsals. It was very much like a water bed, Irwin wrote, and they felt as light as feathers in the weak lunar gravity. They popped in earplugs, pulled down the blinds over the two triangular windows, and drifted into a fitful sleep. Scott arranged his hammock in a fore-to-aft direction above the ascent engine cover, whilst Irwin stretched “athwart ship.”

Despite having long since accepted being here, Scott still succumbed to the temptation to raise the blind and take a long look at the astonishing panorama beyond Falcon’s windows, and called on Irwin to come and take a look. There was, however, little time to wonder and the strictness of the timeline forced them to begin preparations to put on their suits for the first of three Moonwalks. Irwin would subsequently relate, with a hint of humor, that he and Scott did more talking to one another during the donning of the suits than they had in the past several days. With all the added bulk of a backpack, oxygen and water hoses, and electrical cabling, and with the suit fully pressurized, Scott found it surprising that he actually fitted through Falcon’s small, square hatch when the time finally came to venture outside.

The second part of this article will appear tomorrow.

Want to keep up-to-date with all things space? Be sure to “Like” AmericaSpace on Facebook and follow us on Twitter: @AmericaSpace

Did John Young and Gene Cernan perform SEVA’s?

No the A-15 SEVA was a one-off event.

I had the privilege of having lunch with Dave Scott many years ago and I asked him about the SEVA. First he was surprised that I would have remembered the SEVA and after that – that was all he talked about and the wonder of the view. I can not recall what I had to eat for lunch but the conversation was five stars.

A memory of a life time.