It took three tries to get STS-58 off the ground, 25 years ago, this month.

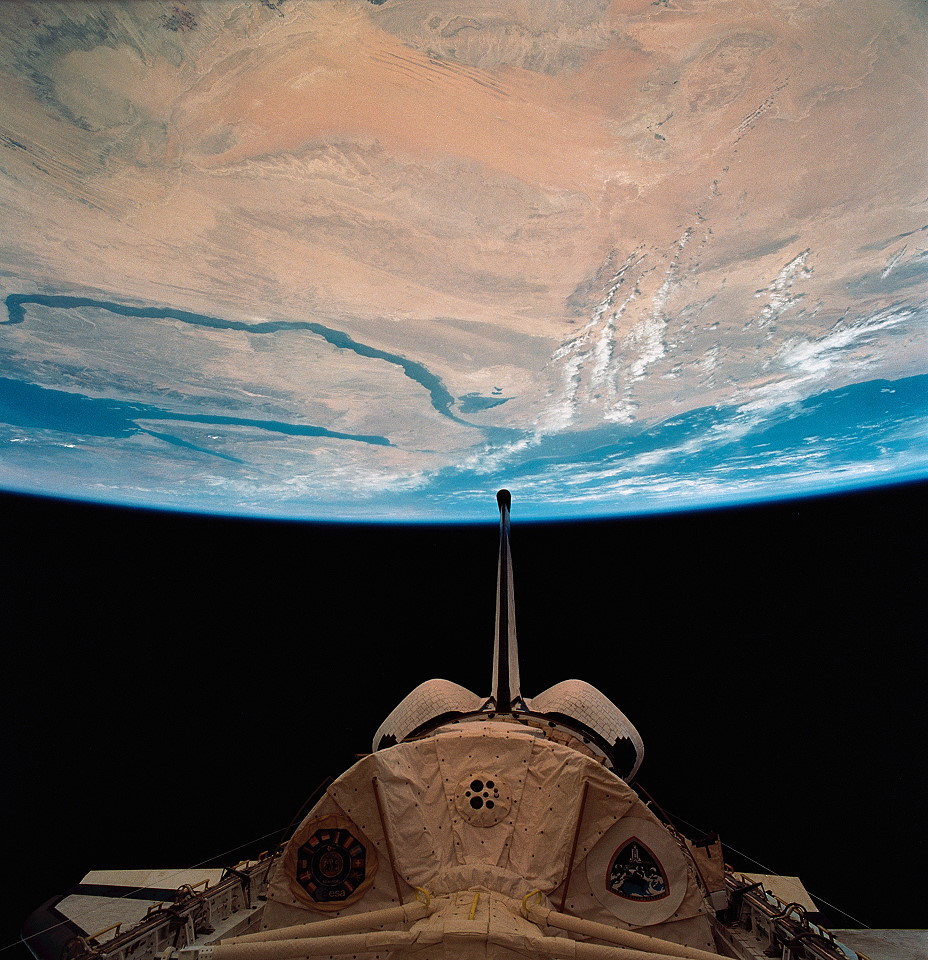

Launch of Columbia on what would be the longest shuttle flight at that time should have taken place on 14 October 1993, carrying a crew of seven—Commander John Blaha, Pilot Rick Searfoss, Payload Commander Rhea Seddon, Mission Specialists Bill McArthur, Dave Wolf and Shannon Lucid and Payload Specialist Marty Fettman—on a 14-day mission to explore the effects of microgravity on the human body. With the second Spacelab Life Sciences (SLS-2) module tucked inside Columbia’s cavernous payload bay, STS-58 promised to be an exciting (and controversial) mission.

Bad weather and the failure of an Air Force range-safety command message encoder-verifier scuppered Columbia’s chances of flying on 14 October and a 24-hour scrub was enforced. Next day, Blaha led his crew out of the Operations & Checkout (O&C) Building at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida and boarded the shuttle uneventfully. However, the 15th would also prove fruitless in getting STS-58 airborne, due to a troublesome S-band transponder. A replacement was rushed out to Pad 39B, but the Mission Management Team (MMT)—then chaired by former shuttle commander Loren Shriver—was unhappy about putting it in the crew cabin during the final minutes before launch, then asking the astronauts to change it out when they reached orbit. “Having been there myself,” Shriver said later, “there is no substitute for having a little help from the ground.”

Aside from undue additional pressure on the crew, Shriver’s main worry centered on the prognosis for a safe landing in the event of a Return to Launch Site (RTLS) abort or other contingency. If the transponder failed, it might leave Blaha and Searfoss out of radio contact with Mission Control for up to 15 critical minutes. As circumstances transpired, the transponder proved a moot issue, as the weather closed in and STS-58’s second launch attempt was scrubbed.

“John, we’re going to fly you one of these days,” Launch Director Bob Sieck told Blaha over the air-to-ground communications link. “Just hang in there.”

“Nice try,” replied Blaha, as his crew wrapped up 2.5 uncomfortable hours on their backs aboard the shuttle.

Standing down for three days, a new transponder was installed and tested and launch was rescheduled for the following Monday morning, 18 October 1993. Donning the bright orange partial-pressure suits on launch morning was one of the worst aspects of a shuttle flight, according to Rhea Seddon in a NASA oral history interview. “It was crazy,” she recalled. “They had technicians that got you into them prior to launch, but then you had to get yourself into them for landing. Imagine the middeck, weightlessness and seven suits floating around down there…and 14 gloves and 14 boots and cooling garments!”

During training, Seddon noted that the difficulty was worse for small astronauts, because they carried the same weight of equipment, regardless of body size. Yet it was about more than just bulk. “Those suits were built to be worn by high-altitude pilots,” she said, “regular-size guys. If they had problems, they ejected. They didn’t have to crawl out and run away. They didn’t have to rappel down the side of their vehicle.” Her concerns were realized in early May 1993, when she broke four metatarsal bones in her left foot, whilst practising a fully-suited escape scenario from the orbiter. “The STS-58 crew was practicing emergency egress,” noted NASA. “As Dr. Seddon was sliding down the slide, her left foot became pinned under her, causing four minor bones to break.” It was fortunate that the injury was minor and that the training was of the refresher nature and therefore could be quickly caught up on after her recuperation.

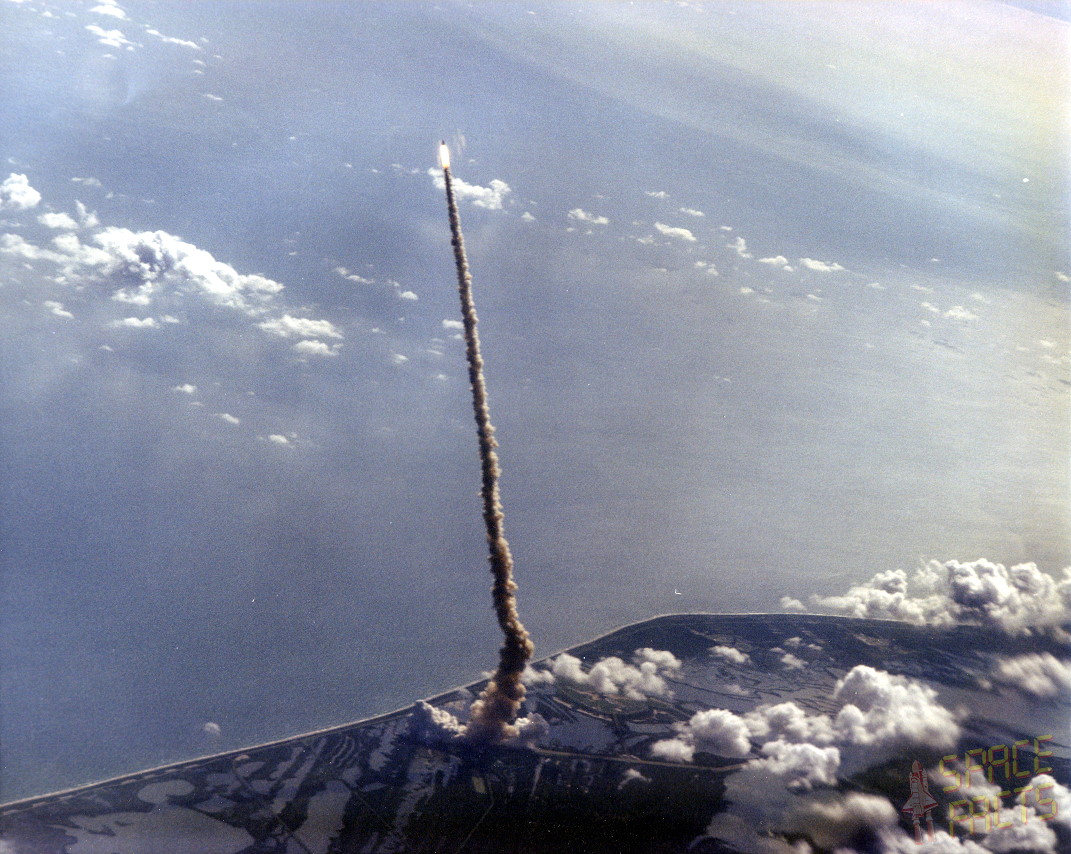

Early on 18 October 1993, the seven astronauts again trooped out to Pad 39B and boarded Columbia. At two minutes before launch, with the clock ticking down to a T-0 at 10:53 a.m. EDT, the reality began to hit home. “Close and lock your visors, initiate O2 flow,” came the call in their headsets. “This time, we’re gonna send you!”

“Roger that, closing visors, suit O2 on,” replied Blaha.

Liftoff was perfect and spectacular, as Columbia rose atop a column of golden flame to begin her 15th voyage into space. And by the time she returned smoothly to Earth on 1 November, she would wrap up the longest shuttle flight at that time—STS-58’s duration nudged slightly over 14 full days—and had returned a vast amount of medical data, including (controversially) the first euthanasia and dissection of lab rats in space. Speaking at the post-flight press conference, Blaha summarized his perspective of his fourth shuttle launch by paying tribute to all those who made it possible. “I really thinking nothing but the highest,” he said, “of all the people who make this happen.”