Only days after triumphantly completing its long-awaited In-Flight Abort Test—destroying a long-serving booster, parachuting an unmanned Crew Dragon to a safe splashdown in the Atlantic Ocean and clearing a significant milestone on the road to returning U.S. astronauts to space aboard U.S. spacecraft, atop U.S. rockets and from U.S. soil—SpaceX aims to launch another Falcon 9 at 9:49 a.m. EST on Monday, 27 January, to continue CEO Elon Musk’s campaign to emplace thousands of Starlink internet communications satellites into low-Earth orbit by the mid-2020s.

The veteran Falcon 9 core tailnumbered “B1051” has been earmarked for this launch, having previously flown on two occasions for the Crew Dragon Demo-1 flight from the East Coast in March 2019, followed by last June’s Radarsat Constellation Mission (RCM) from the West Coast.

Follow our LAUNCH TRACKER for updates and live coverage on launch day!

B1051 becomes the sixth Falcon 9 core in a little over a year to record a third launch. In fact, the very first booster to log three missions, B1046, was intentionally destroyed in Sunday’s In-Flight Abort Test as it was put through its own “Viking Funeral” on its record-tying fourth launch.

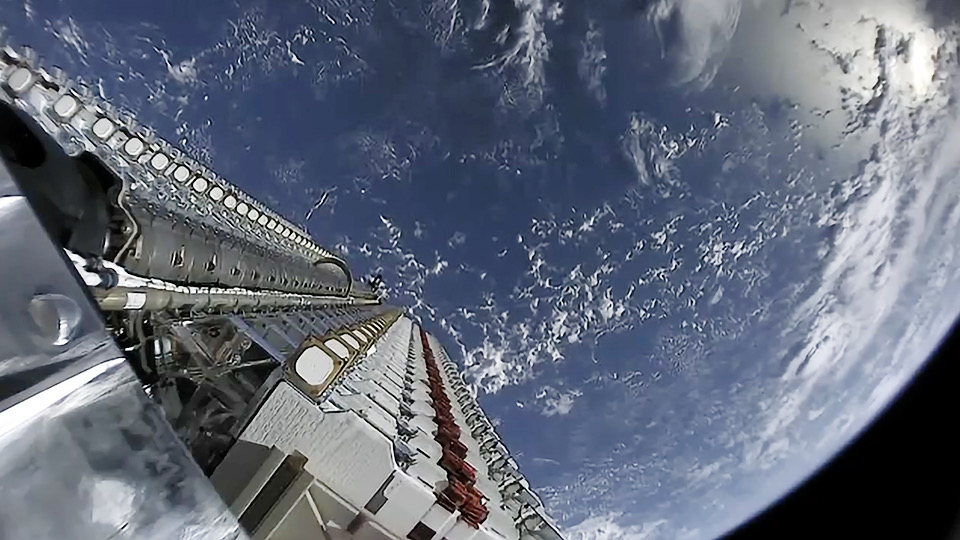

And the primary payload for the third Falcon 9 flight of 2020 is another 60 of SpaceX’s homegrown (and highly controversial) Starlink low-orbiting internet communications satellites. This $10 billion program was described Mr. Musk as a means of revolutionizing low-cost broadband provision and was unveiled during an event in Seattle, Wash., back in January 2015. He identified Starlink as a means of opening the way for competitively-priced services for urban regions and rural and underserved areas of the United States. Under the announced plan, an eventual network of 12,000 satellites could handle up to half of all backhaul communications traffic and a tenth of all local internet traffic in high-population-density cities by the mid-2020s.

Late in 2016, SpaceX described the concept as “non-geostationary” and revealed Starlink’s initial coverage would span the Ku-band and Ka-band regions, between 12-18 GHz and 26.5-40 GHz, respectively. By the late spring of the following year, plans were laid for a second orbital “shell” of satellites to utilize the V-band at 40-75 GHz, which is not routinely used for commercial communications purposes. Previously, the V-band has seen service for millimeter-wave radar research and scientific applications, but it reportedly also has promise for high-capacity terrestrial millimeter-wave communications networks.

SpaceX’s original intent was for 4,425 Ku-/Ka-band Starlinks to reside at an altitude of 710 miles (1,150 km) and 7,518 V-band birds to sit at 210 miles (340 km), producing a total population of these small satellites by the mid-2020s. However, in November 2018 SpaceX received licensing from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to operate a third of the Ku-/Ka-band complement—some 1,584 satellites—at just 340 miles (550 km), much lower than initially planned. This will produce a relatively short operational lifetime of around five years, before they are maneuvered into a disposal orbit for controlled re-entry. SpaceX has explained that all satellite components are “100-percent demisable” and exceed “all current safety standards”, but the sheer volume of Starlinks to be launched in a relatively short period has aroused lingering controversy, both in terms of the work of astronomers and adding to ongoing debate about the effect of space debris.

Two Starlink test satellites, Tintin-A and Tintin-B, were launched in February 2018 and successfully validated the phased-array broadband antenna from an orbital perch 320 miles (515 km) above Earth. Then, last May, the first 60 “production” Starlink satellites were launched atop B1049. Although three of the satellites failed shortly after reaching orbit, the remainder are still healthy. More recently, in November 2019 and earlier this month, a further two batches of 60 Starlinks apiece were boosted to space on the record-setting fourth launches of Falcon 9 cores B1048 and B1049.

SpaceX President Gwynne Shotwell has already confirmed plans to launch further 60-strong sets of Starlinks approximately every two weeks throughout 2020, raising the likelihood that many hundreds of these small satellites will be in orbit by next New Year’s Eve. And that pledge looks set to be matched not only with words, but also with the roar of rocket exhaust, too, for Tuesday’s launch will come exactly two weeks since the last Starlink flight. Assuming an ambitious 24 Starlink launches in 2020, it is also envisaged that SpaceX will stage more than a dozen missions for other customers, including the first manned Crew Dragon missions to the International Space Station (ISS), the first cargo Dragons under the second-round Commercial Resupply Services (CRS2) contract with NASA and three Global Positioning System (GPS) Block III satellites.

Coming so soon after Sunday’s In-Flight Abort Test, a tight schedule awaited this mission, tempered, perhaps, by the fact that the Starlink payload was pre-installed into the Falcon 9 stack. Original plans called for a launch as soon as Tuesday, 21 January. The customary Static Fire Test of the nine Merlin 1D+ first-stage engines at the base of B1051 was conducted on Monday, 20 January, ahead of a planned “instantaneous” window at 11:59 a.m. EST Tuesday.

However, immediately after the Static Fire Test, SpaceX refused to immediately declare a target launch date, stating instead that “Due to extreme weather in the recovery area, team is evaluating best launch opportunity”. With wind speeds predicted to be in the region of 60 mph (96 km/h), the risk not only to the returning B1051 core, but also to the stability of the ASDS itself, was not one that SpaceX was willing to take. Launch was rescheduled for the 24th and eventually, the 27th, which will mark the 53rd anniversary of the Apollo 1 fire, with weather anticipated to be only 40-percent favorable. Conditions are expected to improve markedly to 80-percent favorable in the event of a scrub to Tuesday 28th, the anniversary of the 1986 Challenger disaster.

“A strong upper level jet across the southern US will lead to the development of a weak area of low pressure over the Gulf of Mexico on Sunday,” noted the 45th Weather Squadron at Patrick Air Force Base in its L-3 briefing on Friday morning. “This low is expected to cross the Florida peninsula on Monday, bringing showers and storms through much of the day, including during the launch window. The main concerns during the launch window will be cumulus clouds, disturbed weather and thick clouds.”

Monday’s mission is set to conclude with a landing of the B1051 core on the deck of the East Coast-based Autonomous Spaceport Drone Ship (ASDS), “Of Course I Still Love You”.

.

.

FOLLOW AmericaSpace on Facebook and Twitter!

.

.