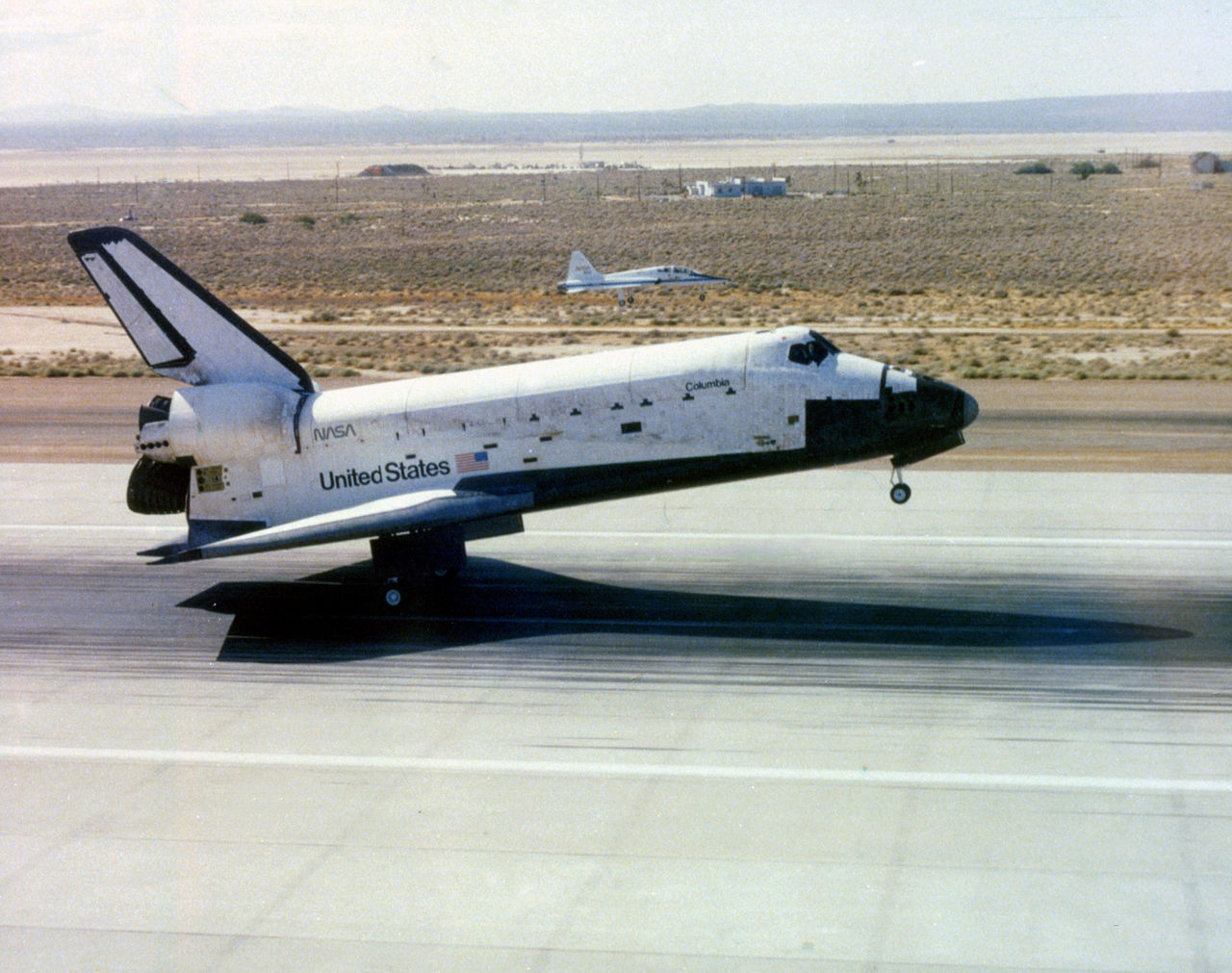

On the morning of 4 July 1982, a rapidly-moving black-and-white speck appeared on the horizon at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., bringing a pair of U.S. space explorers back to Earth after a week in orbit. Minutes later, at 12:09 p.m. EDT (9:09 a.m. PDT), shuttle Columbia and her crew of Commander Ken Mattingly and Pilot Hank Hartsfield alighted on the 15,000-foot-long (4,600-meter) concrete Runway 22, becoming the first American human space mission ever to be in progress on Independence Day, this quintessentially “American” holiday of remembrance.

Many other Americans would follow in Mattingly and Hartsfield’s footsteps, aboard five more missions—including the first shuttle-Mir docking flight—and more have since observed the day’s festivities from the lofty perch afforded by Mir and the International Space Station (ISS). Only one U.S. human mission has ever actually launched on 4 July and only one has ever actually landed on 4 July, but for almost two decades the holiday has been marked by a succession of Americans from a location far higher than even the members of the Second Continental Congress could possibly have imagined when they drafted the language of separation of the Thirteen Colonies way back in 1776.

The first Independence Day spent in orbit by U.S. astronauts began in a rather comical fashion. On 4 July 1982, Mattingly and Hartsfield were in the process of packing away much of their research hardware, after seven days in orbit aboard Columbia. It had been a highly successful mission and the last of four Orbital Flight Tests (OFTs). Among the research performed by Mattingly and Hartsfield were the first classified payload, flown on behalf of the Department of Defense.

“On one experiment, they had a classified checklist [and] because we didn’t have a secure comm link, we had the checklist divided up in sections that just had letter-names, like Bravo-Charlie, Tab-Charlie, Tab-Bravo, that they would call out,” recalled Hartsfield in his NASA oral history interview. Whenever the astronauts spoke to U.S. Air Force controllers at the Satellite Control Facility in Sunnyvale, Calif., they would be told, for example, to “Do Tab-Charlie”.

“We had a locker that we kept all the classified material,” continued Hartsfield, “and it was padlocked, so once we got on orbit, we unlocked it and did what we had to do.” As the end of the mission neared, Hartsfield packed away the remainder of the classified materials and secured the locker. He told Mattingly. “I got all the classified stuff put away. It’s all locked up.”

“Great!” replied Mattingly.

Half an hour later, Mission Control told them that the military staff at Sunnyvale wanted to talk to them. The Air Force controller asked them, cryptically, to “do Tab-November”. The two astronauts looked at each other, bewildered. What the hell was Tab-November? Neither could remember. The secretive nature of the military instruction and the lack of a secure communications link also meant they could not ask over the radio. The only option was to reopen the classified locker, dig through all the materials and find the checklist. Eventually, after much searching, Hartsfield finally found the glossary entry for Tab-November.

It read: Put everything away and secure it!

Mattingly and Hartsfield’s arrival in the California desert was being watched closely by President Ronald Reagan and First Lady Nancy Reagan and the astronauts had been briefed by NASA Administrator Jim Beggs and asked to think of some memorable words. “We knew they had hyped-up the STS-4 mission, so that they wanted to make sure we landed on the Fourth of July,” Mattingly recalled in his NASA oral history. “It was in no uncertain terms that we were going to land on the Fourth of July, no matter what day we took off. Even if it was the Fifth, we were going to land on the Fourth! That meant, if you didn’t do any of your test mission, that’s okay, as long as you land on the Fourth, because the President is going to be there. We thought that was kinda interesting!”

Fortunately, Columbia’s landing—the first on Edwards’ concrete Runway 22—occurred precisely on time. The vehicle alighted on the runway and Mattingly applied the brakes for 20 seconds to come to a smooth halt. Now came his biggest challenge: How to welcome the Reagans inside the shuttle. He and Hartsfield considered putting up a notice, worded to the effect of Welcome to Columbia: Thirty minutes ago, this was in space.

Unfortunately, things did not quite pan out that way.

Right after wheelstop, Mattingly turned to Hartsfield. “I am not going to have somebody come up here and pull me outta this chair! I’m going to give every ounce of strength I’ve got and get up on my own!” Previous crews had come back to Earth, some feeling fine, others feeling nauseous, and still others required a gurney to carry them off the spacecraft for medical attention. That would not happen with the president in attendance. Mentally and physically set up to meet the chief, Mattingly pushed himself upward out of his seat…and smashed his head sharply on the overhead instrument panel!

“That’s very graceful,” Hartsfield quipped.

Nevertheless, the two returning space heroes composed themselves and Mattingly wiped away the few spots of blood. In the minutes before Columbia’s hatch was opened, they walked around the middeck, to get themselves acclimated, before descending the steps to meet the Reagans. Hartsfield—well known for his merciless sense of humor—was on top form that day. “Well, let’s see. If you do it like you did gettin’ out of your chair, you’ll go down the stairs and you’re going to fall down, so you need to have something to say,” he told Mattingly. “Why don’t you just look up at the president and say ‘Mr. President, those are beautiful shoes? Think you can get that right?”

Twenty-four years later, on 4 July 2006, Discovery inadvertently became the only U.S. human space mission to actually launch on Independence Day. Aboard the shuttle, STS-121 Commander Steve Lindsey, Pilot Mark Kelly and Mission Specialists Mike Fossum, Lisa Nowak, Stephanie Wilson and Piers Sellers were bound for the second return-to-flight test mission to the ISS, following the loss of Columbia. They were also ferrying German astronaut Thomas Reiter into orbit for the European Space Agency’s (ESA) first multi-month stay aboard the station. Walking out of crew quarters, the astronauts waved American flags, with the exception of Reiter, who fluttered a German tricolor. “I don’t know if it was the German Fourth of July or not!” Lindsey quipped at the post-flight press conference.

“And liftoff of the Space Shuttle Discovery,” came the call from the launch announcer at 2:55 p.m. EDT, as STS-121 speared into a crystal clear Florida sky, “returning to the space station, paving the way for future missions beyond.”

Those missions beyond will undoubtedly see a future crew of Americans either launch or land on Independence Day, although at the time of writing the feats of Mattingly and Hartsfield in 1982 and Lindsey and his crew in 2006 have not been repeated. That said, three other crews were in orbit over the holiday, including STS-50 and STS-78, which both set record durations for the longest shuttle missions of their day, as well as STS-71, the first Mir docking flight. Three other Americans also celebrated aboard Mir during their long-duration increments and, since July 2001, there has been a U.S. presence aboard the ISS for every Independence Day.

Just last year, Expedition 59 astronauts Christina Koch and Nick Hague—backdropped by a Stars and Stripes flag on the wall of the Destiny lab and both sporting red, white and blue socks—offered their good wishes to the planet and, in particular, to U.S. service personnel across the globe. “Through history, our flag has traveled with humans and robots to the farthest reaches of the Solar System,” Koch explained, “as American ingenuity and leadership has pushed the boundaries of what’s possible, through grit, determination and imagination.”

Today, as Expedition 63 Commander Chris Cassidy and his U.S. crewmates Doug Hurley and Bob Behnken observe the United States’ 244th Independence Day, they join the ranks of many others who have done likewise. In fact, this is Cassidy’s second Fourth of July in space, having also celebrated the holiday in 2013 during his Expedition 36 increment. All told, since Mattingly and Hartsfield’s pioneering landing all those years ago, nearly 60 Americans have witnessed 4 July in space, of whom seven—including Cassidy—have done so twice. It will certainly be true that many more will follow in their foorsteps.