Earlier this year, a SpaceX Falcon 9 booster shattered a launch-to-launch record which had stood intact and unchallenged for more than three decades. The B1058 core, newly returned from sending Dragon Endeavour crewmen Doug Hurley and Bob Behnken to the International Space Station (ISS) on 30 May, flew a second time on 20 July to loft South Korea’s ANASIS-II military communications satellite.

In doing so, it set a new record of 51 days for the shortest interval between two launches by an orbital-class vehicle. And it broke a long-standing record set 35 years ago tonight by shuttle Atlantis. On 26 November 1985, only 54 days after rocketing away from Earth on her maiden voyage, Atlantis launched again in what would remain an unbeaten record throughout the shuttle era.

Turnaround times between missions by individual shuttles varied significantly in the pre-Challenger (1981-1986), post-Challenger (1988-2003) and post-Columbia (2005-2011) eras, as improved work processes, improved technologies and more mature practices were juxtaposed against greater emphases upon differing aspects of safety and maintainability.

Before the loss of Challenger on STS-51L in January 1986, turnarounds of individual orbiters between “operational” missions averaged 89 working days or less. In the post-Challenger era, this increased to a mean of 147 working days and following the resumption of shuttle operations after the February 2003 loss of Columbia, increased yet further to a mean of 326 working days. But in the fall of 1985, with the shuttle enjoying its halcyon days, these complex vehicles were being touted as the spacefaring equivalent of commercial airliners and Atlantis would enjoy a brisk turnaround.

Having landed at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., on 7 October, following the highly secretive STS-51J mission for the Department of Defense, she was flown back to the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida atop NASA’s Boeing 747 Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (SCA), to be wheeled through the doors of Orbiter Processing Facility (OPF) Bay 1 on the 12th.

Astonishingly, Atlantis underwent post-flight deservicing and reconfiguration for STS-61B in only 27 days, before she was rolled over to High Bay 3 of the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) on 8 November. Four days later, she was hauled out to historic Pad 39A for final preparations for the shuttle program’s second night launch.

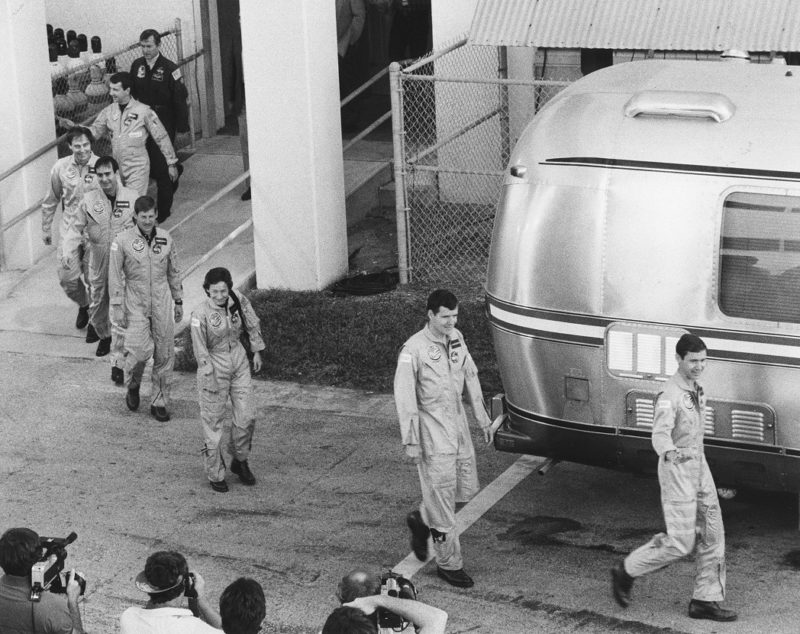

Weather conditions that night were good on the Space Coast, with one of the Transoceanic Abort Landing (TAL) sites reporting itself “No-Go” on account of heavy cloud cover. Commanded by 40-year-old Brewster Shaw, the youngest man ever to lead a mission by Atlantis, STS-61B went on to deploy three communications satellites—Australia’s Aussat-2, Mexico’s Morelos-B and the high-powered Satcom Ku-2 for RCA Americom—and supported three sessions of Extravehicular Activity (EVA) to evaluate construction methodologies for Space Station Freedom, forerunner of today’s ISS. Its seven-member crew also included Mexico’s first man in space, Rodolfo Neri Vela, flying to observe the deployment of his nation’s Morelos payload.

Liftoff of STS-61B was timed precisely for 7:29 p.m. EST, right on the opening of a nine-minute “window” for that evening. “It was a perfect night,” remembered mission specialist Sherwood “Woody” Spring in a NASA oral history interview. “We had a full Moon, the day before Thanksgiving, severe, clear, not a cloud in the sky; it was a gorgeous night.”

Spring was seated on Atlantis’ middeck, alongside Neri and fellow payload specialist Charlie Walker of McDonnell Douglas. Upstairs on the flight deck were Shaw, pilot Bryan O’Connor, flight engineer Mary Cleave and mission specialist Jerry Ross.

It was not until relatively close to the flight that the crew realized they would be launching in the hours of darkness. And as the final seconds ticked away, O’Connor looked across the cabin towards Shaw and noticed that the commander had momentarily removed his gloves to wipe sweat from his hands. “Oh, my God,” O’Connor thought. “My commander, who’s been through this before, his hands are sweating? Why aren’t mine sweating? I need to be nervous now, if he’s nervous!”

The ignition of Atlantis’ three main engines, Spring reflected, was like a roomful of lions, roaring directly behind him. “And you can feel it,” he said. “This vehicle’s alive. Then the main engines gimbal, getting ready. From the moment of Main Engine Start, you get one and a half seconds where the vehicle actually swings about three degrees of arc and then comes back again. Then the Solid Rocket Boosters ignite.” With a force not unlike the thump of a giant sledgehammer, Shaw and his crew were pushed away from Pad 39A in what Spring could only describe as “a barn-burner”.

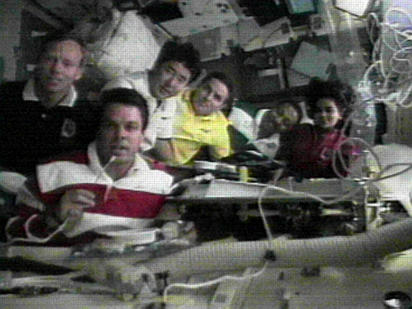

Rising into the night atop the golden pillars of fire from her boosters, Atlantis’ climb to orbit was reportedly visible as far north as the Carolinas and as far south as the southern tip of Florida. Eight minutes later, as the shuttle settled into space, Spring released a pencil and watched as it floated freely in front of his eyes. With only Shaw and Walker having flown before, five of the astronauts on STS-61B had never flown before. Spring let out a whoop of delight, as Cleave giggled excitedly over the intercom. They were in space.

They also became the first shuttle mission—and only the second American crew, following the final team of Skylab astronauts—to observe Thanksgiving in space. Shaw and his crew munched their way through irradiated turkey, pumpkin bread, mashed potatoes, beans and a somewhat tasteless concoction of gravy.

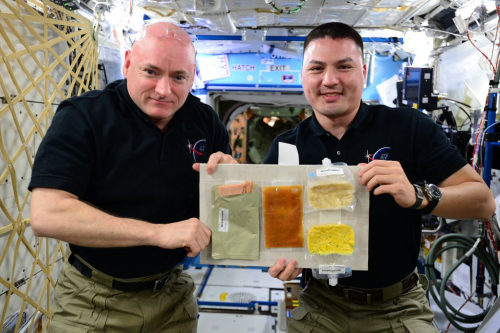

“The gravy didn’t taste very good to me,” O’Connor said later. “The mashed potatoes were great…but I didn’t go for that turkey.” In years to come, a further seven shuttle crews celebrated the holiday in orbit, as did two U.S. astronauts aboard Russia’s Mir space station and at least one American citizen aboard the ISS every year from 2000 to the present day.

Food and fun aplenty has characterized Thanksgiving in space. In November 1973, Skylab astronauts Jerry Carr, Ed Gibson and Bill Pogue performed an EVA on the day itself and later feasted on prime ribs, turkey and chicken, whose bland taste in microgravity was enhanced a little with salt and other condiments. Following STS-61B, the next two Thanksgiving shuttle crews—STS-33 in November 1989 and STS-44 in November 1991—were Department of Defense missions, both commanded by future NASA Deputy Administrator Fred Gregory. And he certainly appreciated the chance to share a “civilized” meal with his crewmates, eating food on a tray, rather than grabbing a bite on the fly.

Since November 2000 and the dawn of permanent habitation of the ISS, at least one American has been aboard the orbital outpost for every Thanksgiving. Expedition 1 skipper Bill Shepherd and his Russian crewmates Yuri Gidzenko and Sergei Krikalev were four weeks into their stay aboard the station on the big day, yet they still found time in a chocked-full work schedule to enjoy a meal of ham and smoked turkey. Including the current Expedition 64 crew, more than 70 Americans have now celebrated the holiday in orbit, including Story Musgrave and Peggy Whitson who did so three times apiece.