As Sierra Nevada Corp. (SNC) heads toward the maiden voyage of its cargo-carrying Dream Chaser vehicle to the International Space Station (ISS) next year, the Sparks, Nev.-headquartered organization has received approval to re-enter and land at the repurposed Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF) at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida.

Having supported no fewer than 78 landings by the shuttle fleet between February 1984 and July 2011, the swamp-fringed concrete runway also saw service in May 2017 and October 2019 in welcoming home the U.S. Space Force’s X-37B Orbital Test Vehicle (OTV), together with demonstration flights of the Morpheus craft and extensive commercial use.

With yesterday’s announcement, SNC clears another milestone in advance of the first flight of Dream Chaser to the International Space Station (ISS), atop the second United Launch Alliance (ULA) Vulcan-Centaur heavylifter, anticipated sometime in 2022. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Office of Commercial Space Transportation awarded the re-entry site license to Cape Canaveral Spaceport Shuttle Landing Facility on 8 February at the request of Space Florida, the state’s aerospace economic development agency.

This makes it the first commercially-licensed re-entry location. When Dream Chaser alights on the 15,000-foot-long (4,600-meter) SLF at some point next year, it will become the very first spacecraft to return from the space station to a runway landing since shuttle Atlantis’ last landfall on the Space Coast way back in July 2011.

“Dream Chaser is the only commercial, lifting-body space vehicle capable of a runway landing, anywhere in the world,” said SNC CEO Fatih Ozmen. “That’s how astronauts prefer to travel to and from space and it’s no wonder. The opportunity for our spaceplane to land on this historic runway, where so many shuttle missions did before, underscores both the practical advantages of Dream Chaser and its time-honored place in NASA’s space exploration heritage.”

Mr. Ozmen’s words were echoed by three-time shuttle astronaut Janet Kavandi, who currently serves as executive vice president of the SNC Space Systems business area after a tenure as director of NASA’s Glenn Research Center (GRC) in Cleveland, Ohio, between March 2016 and September 2019.

“A runway landing capability provides significant advantages over other return options,” said Dr. Kavandi, who flew shuttles Discovery in June 1998, Endeavour in February 2000 and Atlantis in July 2001 and returned safely to a smooth SLF landing at the end of all three missions.

“I understand how a spaceplane provides a safer and more benign entry experience for humans, as well as delicate payloads. Astronauts can immediately depart the vehicle and researchers have access to their experiments almost immediately after landing.”

In its post-shuttle life, the SLF is now known by Space Florida as the Launch and Landing Facility and part of the re-entry site license included a complex environmental assessment in collaboration with NASA, the FAA, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services, the National Park Service and the local community.

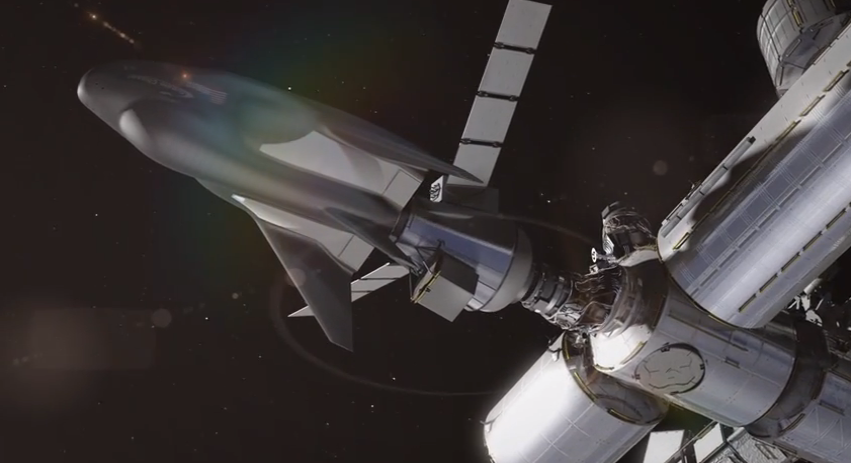

Looking not dissimilar to a scaled-down version of the shuttle, Dream Chaser has the ability to touch down at any licensed landing site with a suitable 10,000-foot-long (3,000-meter) runway capable of handling a typical commercial jet. Its low-G re-entry characteristics, together with a runway landing, are expected to afford greater protection for sensitive ISS research payloads and immediate access by scientists to their results after touchdown.

Last year, SNC named its first Dream Chaser vehicle as “Tenacity”; a particulatly apt moniker which the organization hoped would represent “a beacon of hope that American ingenuity and tenacity will bring brighter days ahead”.

Dream Chaser’s journey from the drawing-board to actual hardware has been a long, tough and convoluted one. In development for almost two decades—having been publicly announced way back in September 2004—it was originally hoped that the spaceplane would play a role in the Commercial Crew Program.

In August 2012, SNC received $212.5 million in Commercial Crew integrated Capability (CCiCap) funds, with hopes that it might someday launch atop a ULA Atlas V rocket and deliver crews of up to seven astronauts to the ISS. But in September 2014 it lost out to Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner and SpaceX’s Crew Dragon, a decision against which SNC mounted an ultimately unsuccessful challenge.

However, in March 2015 the organization reinvented its ship as the Dream Chaser Cargo System to restock the ISS in an uncrewed capacity and in January 2016 was selected alongside SpaceX and Orbital ATK (now part of Northrop Grumman Corp.) as winners of the second-round Commercial Resupply Services (CRS2) contract. Under the terms of its contractual obligation to NASA, SNC would fly at least six Dream Chaser missions to the space station in the 2019-2024 timeframe.

Although physically identical to its earlier crew-carrying variant, as part of the CRS2 requirement the spaceplane would feature an innovative and versatile folding-wing structure, which enables it to fit within the Payload Fairing (PLF) of any sufficiently capable launch vehicles, including ULAs Atlas V and Europe’s Ariane 5. It was also revealed that Dream Chaser would carry a 16-foot-long (4.8-meter) cargo container, known as “Shooting Star”, which will be disposed of in the upper atmosphere at the end of each mission.

In July 2017, SNC chose ULA to launch its first two Dream Chaser missions in 2020 and 2021, initially atop the Atlas V, although in August 2019 it was reported that the spaceplane would utilize the in-development Vulcan-Centaur instead. The latter is targeted to make its maiden voyage from Space Launch Complex (SLC)-41 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Fla., later this year, with an expectation that the inaugural Dream Chaser will ride the heavylift booster’s second voyage at some stage in 2022.

As for the actual Dream Chaser itself, the primary spacecraft structure—measuring 30 feet (9.1 meters) long, with a wingspan of 15 feet (4.6 meters) and weighing some 2,200 pounds (1,000 kg)—was delivered by subcontractor Lockheed Martin from its Fort Worth, Texas, plant to SNC’s integration facility in Louisville, Colo., in October 2019.

In the months thereafter, it received several other major components. Its wings and Wing Deployment System (WDS) arrived last April, followed by its Shooting Star cargo container last May, ahead of a key integration phase which included installation of the SNC-built Passive Common Berthing Mechanism (PCBM) to permit Dream Chaser to berth at the space station’s Unity or Harmony nodes.

Last June, the first of around 2,000 heat-resistant tiles—a critical element of the spaceplane’s Thermal Protection System (TPS)—were delivered and technicians began bonding them onto Dream Chaser’s airframe. More recently, last November integration and testing of the wings on the SNC production floor in Louisville, Colo., got underway, with an expectation that they will be installed onto Tenacity’s airframe this coming summer.

Oh, look! Some new technology that was invented back in the sixties by the Legacy Lobby Aerospace companies that focuses on low-earth orbit stuff. I bet the Chinese are scared to death.

Can snickering Chinese Moon colonists be heard in low-earth orbit? What’s next? A miniature copy of the Wright Flyer? Why not “reinvent” Archimedes screw kite too while skipping down memory lane?

Elon! Help!!!

Now let’s take it to the next level I’m down with it can’t wait to see it go in to space