When Expedition 57/58 astronaut Anne McClain boarded the International Space Station (ISS) in December 2018, she quickly found what she described as “my new favorite spot”.

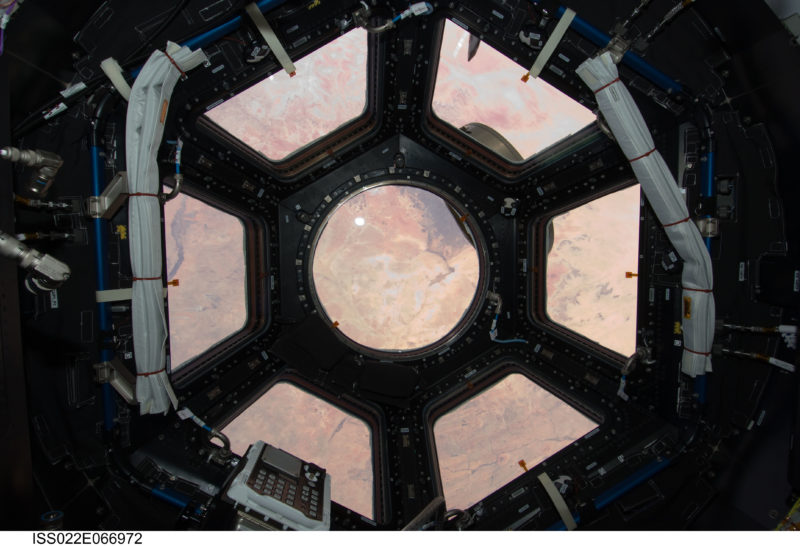

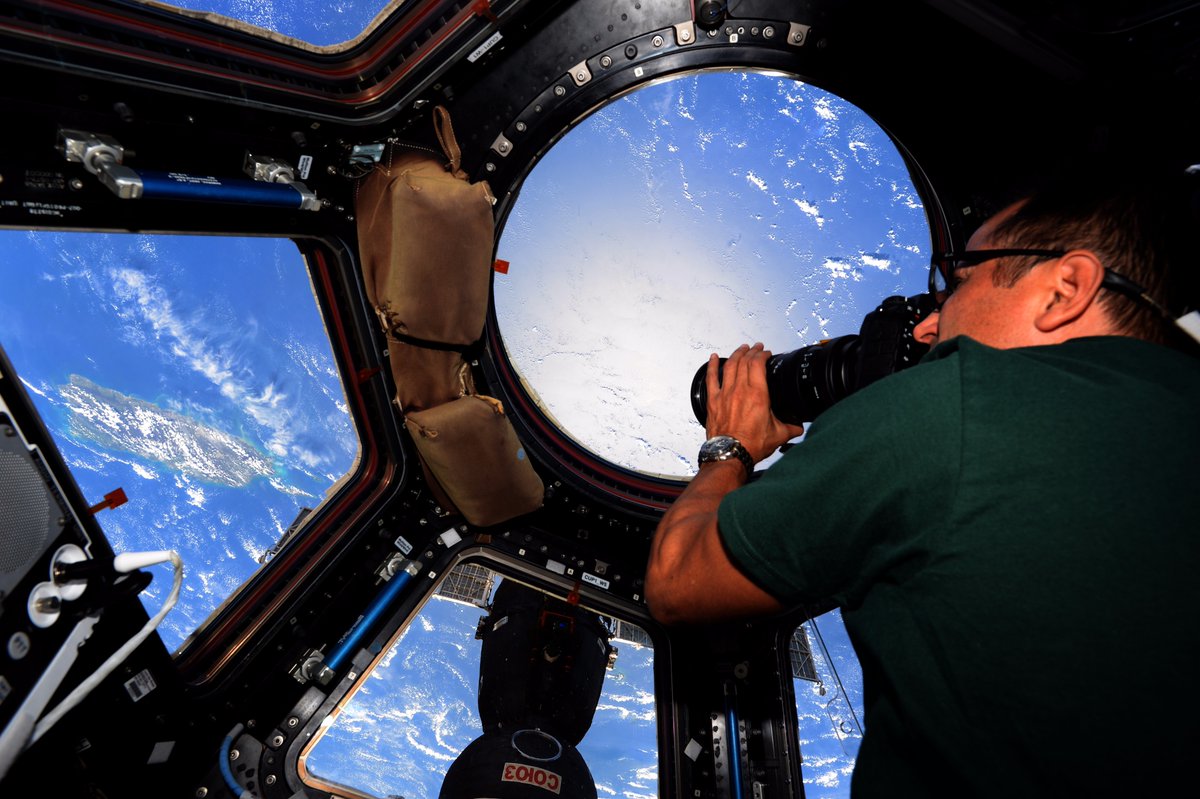

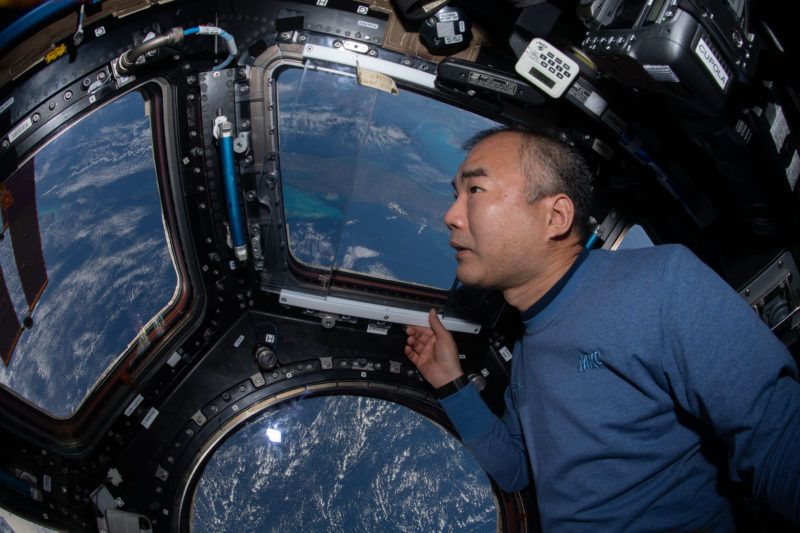

That spot was the multi-windowed cupola, which sits affixed to the Earth-facing (or “nadir”) port of Tranquility Node-3 and whose seven observation ports—six circumferential ones and a large circular one at the apex—have been utilized many times over the past decade to view the Earth and the arrivals and departures of no fewer than 43 uncrewed visiting cargo vehicles, most recently just last month. McClain was not alone in prizing the cupola’s panoramic view of the Home Planet as the station’s most spectacular location.

Today, it celebrates 11 years since the six astronauts of STS-130—shuttle Endeavour’s second-to-last orbital voyage—launched it to orbit and, in doing so, completed the delivery of the last major U.S.-provided ISS component.

Commanded by veteran astronaut George Zamka, who previously flew the shuttle mission which furnished the ISS with the Harmony node to bridge the United States’ Destiny lab, Japan’s Kibo lab and Europe’s Columbus lab, the STS-130 crew included future ISS skipper Terry Virts in the pilot’s seat aboard Endeavour and mission specialists Kay Hire, Steve Robinson, Nick Patrick and future Chief Astronaut Bob Behnken.

They were assigned to the flight in December 2008, with an initial expectation that they would launch in December 2009, but a shifting shuttle manifest eventually found them finally boarding Endeavour for the shuttle program’s final “night-time” launch on 8 February 2010. A liftoff attempt the previous evening had been thwarted by a dense pall of cloud which hung ominously low over the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida.

Lighting up the darkened Space Coast, Endeavour sprang from historic Pad 39A at 4:14 a.m. EST to begin her two-day pursuit of the space station and its waiting Expedition 22 crew of Commander Jeff Williams and his crewmates Max Surayev and Oleg Kotov of Russia, Japan’s Soichi Noguchi—who, incidentally, is aboard the ISS again today as a member of Expedition 64—and NASA astronaut and future flight director Timothy “T.J.” Creamer.

Watching the imagery after the flight, Zamka was astonished to see the shuttle stack punch straight through a cloud-deck and create a peculiar optical effect which reminded him, fittingly, of the shape of a cupola.

Shortly after reaching orbit, Zamka and Virts set to work preparing their ship for maneuvers necessary to reach the ISS, whilst their crewmates set up Extravehicular Activity (EVA) tools and suits and readied cameras for the approach and rendezvous. They also conducted customary checks of the shuttle’s heat-resistant tiles and Reinforced Carbon Carbon (RCC) surfaces—specifically around the nose-cap and the leading edges of the wings—which were mandated in the aftermath of the Columbia disaster.

Docking at the forward port of the station’s Harmony node took place without incident a few minutes after midnight EST on 10 February, as both spacecraft flew high above Portugal. The two crews participated in a brief welcoming ceremony and safety briefing, then headed straight to work, with Zamka and Noguchi laboring to re-size Behnken’s space suit ahead of the first EVA.

It had earlier suffered a failure of its power harness, needed for wireless video and the in-glove heaters. With this complete, Behnken and Patrick performed an overnight camp-out in the Quest airlock, before opening the hatches for their first 6.5-hour spacewalk late on the evening of the 11th.

Shortly after they stepped outside, Virts and Hire maneuvered the Tranquility node and attached cupola out of Endeavour’s payload bay, by means of the Remote Manipulator System (RMS) mechanical arm, and smoothly mated it to the port side of the Unity node. Measuring 22 feet (6.7 meters) long and 14.7 feet (4.4 meters) in diameter, the cylindrical node was equipped with six Common Berthing Mechanisms (CBMs)—one each at its forward and aft “ends” and four circumferential ones—and provided by the European Space Agency (ESA) and Italian Space Agency (ASI) as part of a “barter” arrangement with NASA.

Working swiftly, Behnken and Patrick attached power and data cables, as a further 2,600 cubic feet (73.6 cubic meters) of pressurized volume was added to the expansive orbiting lab. With the new node in place, the hatches were opened and, wearing protective masks and goggles to guard against the risk of floating debris, the astronauts floated inside and began activating equipment.

They also moved parts for the advanced Resistive Exercise Device (aRED) and an Air Revitalization System (ARS) rack into Tranquility. Early on St. Valentine’s Day, Behnken and Patrick wrapped up a second EVA, this time lasting just shy of six hours, to connect ammonia coolant loops and install thermal covers over ammonia hoses.

Unfortunately, a minor leakage of ammonia from a connector obliged mission controllers to terminate the spacewalk a little earlier than intended. This afforded the astronauts extra time to run through decontamination and solar “bake-out” operations before returning inside the station.

Next day, the cupola windows—about which Anne McClain would write with such enthusiastic vigor—were finally opened. The small module was robotically moved from its launch configuration on the port “end” of Tranquility to the Earth-facing (“nadir”) side of the node, offering it a spectacular view of the Home Planet.

With Virts and Hire operating the RMS, the relocation was swiftly accomplished and the cupola shutters were dramatically opened. Late on 15 February, as Behnken and Patrick toiled outside on their third spacewalk, Virts gingerly opened each shutter in turn. Hire likened it to “raising the curtain on a bay window to the world”.

After almost ten days of docked activities, Endeavour pulled away from the ISS on the evening of 19 February to begin her return home. And at 10:20 p.m. EST on the 21st, after traveling 5.7 million miles (9.2 million km), Zamka and Virts guided their ship to a smooth halt on the Shuttle Landing Facility (SLF) at her homeport, KSC in Florida.

All told, their mission had delivered 36,000 pounds (16,300 kg) of hardware to the station and Behnken and Patrick’s trio of spacewalks—totaling over 18 hours—had played a crucial role in completing the construction of this mammoth outpost in the sky.

Of course, all minds were by now keenly aware that the shuttle program was winding down towards its retirement in 2011. For four members of the STS-130 crew, it would be their last experience of flying in space. But for Behnken, the years ahead would see a tenure as chief of NASA’s astronaut corps, ahead of assignment to the Commercial Crew Program and a historic return to space in 2020 aboard Dragon Endeavour.

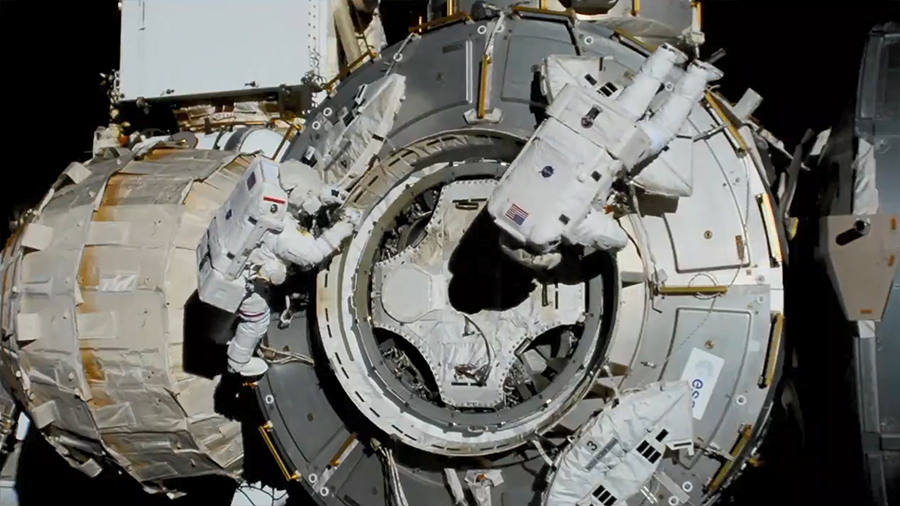

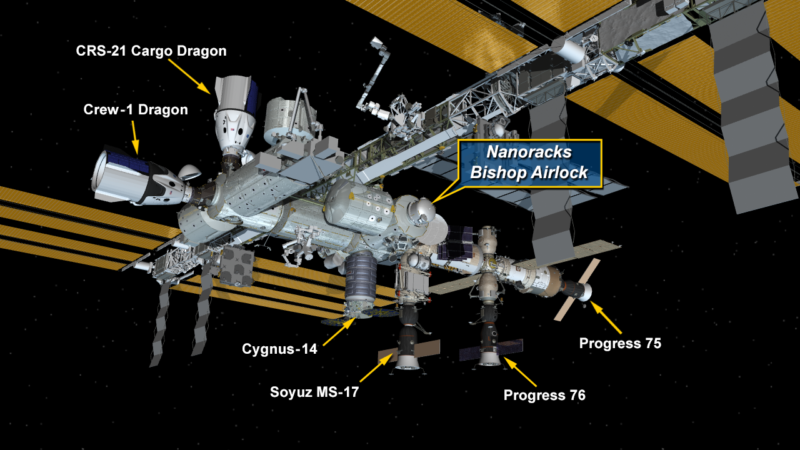

Last July, on a spacewalk with Expedition 63 Commander Chris Cassidy, Behnken worked on the exterior of Tranquility once more, laboring to prepare one of its CBMs for the arrival of NanoRacks’ Bishop commercial airlock module.

And although the cupola, in particular, has been oft-touted over the years for its jaw-dropping perspective of the Home Planet, one of its primary functions has been to provide visual assistance in the robotic capture of visiting cargo vehicles. Since the arrival of Japan’s second H-II Transfer Vehicle (HTV-2) in January 2011, it supported the arrival and departure of 43 uncrewed spacecraft on the U.S. Operational Segment (USOS): a total of eight HTVs, 14 Northrop Grumman Corp. Cygnus ships and 21 SpaceX Dragons.

Nor has Tranquility itself been idle. In addition to serving as the nerve-center for the space station’s Environmental Control and Life Support System (ECLSS), the location of its exercise gear and the crew’s toilet, its CBMs have been a hive of activity. With the starboard “end” of the node connected to the port side of Unity, its port-facing end initially received Pressurized Mating Adapter (PMA)-3, in part to afford Tranquility improved Micrometeoroid Orbital Debris (MMOD) protection.

More recently, in March 2017, PMA-3 was robotically relocated from its berth on Tranquility over to the space-facing (or “zenith”) port of Harmony, ahead of its future role supporting an International Docking Adapter (IDA) for Commercial Crew missions. After the removal of PMA-3, the port-facing end of Tranquility remained unoccupied until December 2020, when NanoRacks’ newly-arrived Bishop commercial airlock was robotically installed there for an anticipated two years of operational service.

Two of Tranquility’s other ports have also seen substantial activity in recent years. The Leonardo Permanent Multipurpose Module (PMM)—originally a short-stay Multi-Purpose Logistics Module (MPLM), which flew eight times aboard the shuttle between March 2001 and February 2011—was moved to Tranquility’s forward-facing port in May 2015.

There it continues its principal role as a storage location for the U.S. Operational Segment (USOS). And in April 2016, the Bigelow Expandable Activity Module (BEAM) arrived at the space station and was affixed to Tranquility’s aft-facing port a month later.

2 Comments

2 Pings & Trackbacks

Pingback:NASA, AxiomSpace Leaders Discuss Historic Ax-1 Space Station Mission

Pingback:NASA, AxiomSpace Leaders Discuss Historic Ax-1 Space Station Mission « AmericaSpace