Thirty years ago today, the crew of STS-54 settled into orbit for one of the shortest Space Shuttle missions of the 1990s, tasked with deploying NASA’s fifth Tracking and Data Relay Satellite (TDRS-F). Attached to a Boeing-built Inertial Upper Stage (IUS) booster, TDRS-F was released from Endeavour’s payload bay a few hours into the six-day mission to facilitate critical voice and data communications from geostationary orbit for the benefit of future shuttle crews and major scientific instruments, including NASA’s showpiece Hubble Space Telescope (HST) and the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory (CGRO).

Commanding STS-54 was veteran astronaut John Casper, who had previously piloted a classified Department of Defense mission three years earlier. He was initially assigned to pilot another flight, before the retirement of two senior shuttle commanders in the summer of 1991 prompted NASA to reassign Casper to his first command.

Joining Casper aboard Endeavour for STS-54 was Pilot Don McMonagle and Mission Specialists Greg Harbaugh, Mario Runco and Susan Helms; all had flown before, except for Helms, a U.S. Air Force major who became America’s first active-duty military female spacefarer. Selected into NASA’s astronaut corps in January 1990, Helms was a keen keyboardist and carried a mini-keyboard on STS-54 to tap out a one-finger rendition of the Air Force anthem, “Wild Blue Yonder”.

In addition to the 45-foot-long (13.7-meter) TDRS-F/IUS stack—which totaled 38,256 pounds (17,353 kilograms) and filled more than two-thirds of the payload bay—Endeavour also carried the twin detectors of the Diffuse X-ray Spectrometer (DXS). This sophisticated astrophysics instrument was mounted onto a pair of Hitchhiker panels on opposing walls of the shuttle’s payload bay.

DXS originally formed part of a larger payload called the Shuttle High Energy Astrophysics Laboratory (SHEAL), which would have flown alongside the Broad Band X-ray Telescope (BBXRT). However, the latter instrument was completed ahead of schedule and was moved forward on the shuttle flight manifest and added to the STS-35 mission, which flew in December 1990. As a result, DXS was juggled between a couple of other flights, before eventually settling as a secondary payload on STS-54.

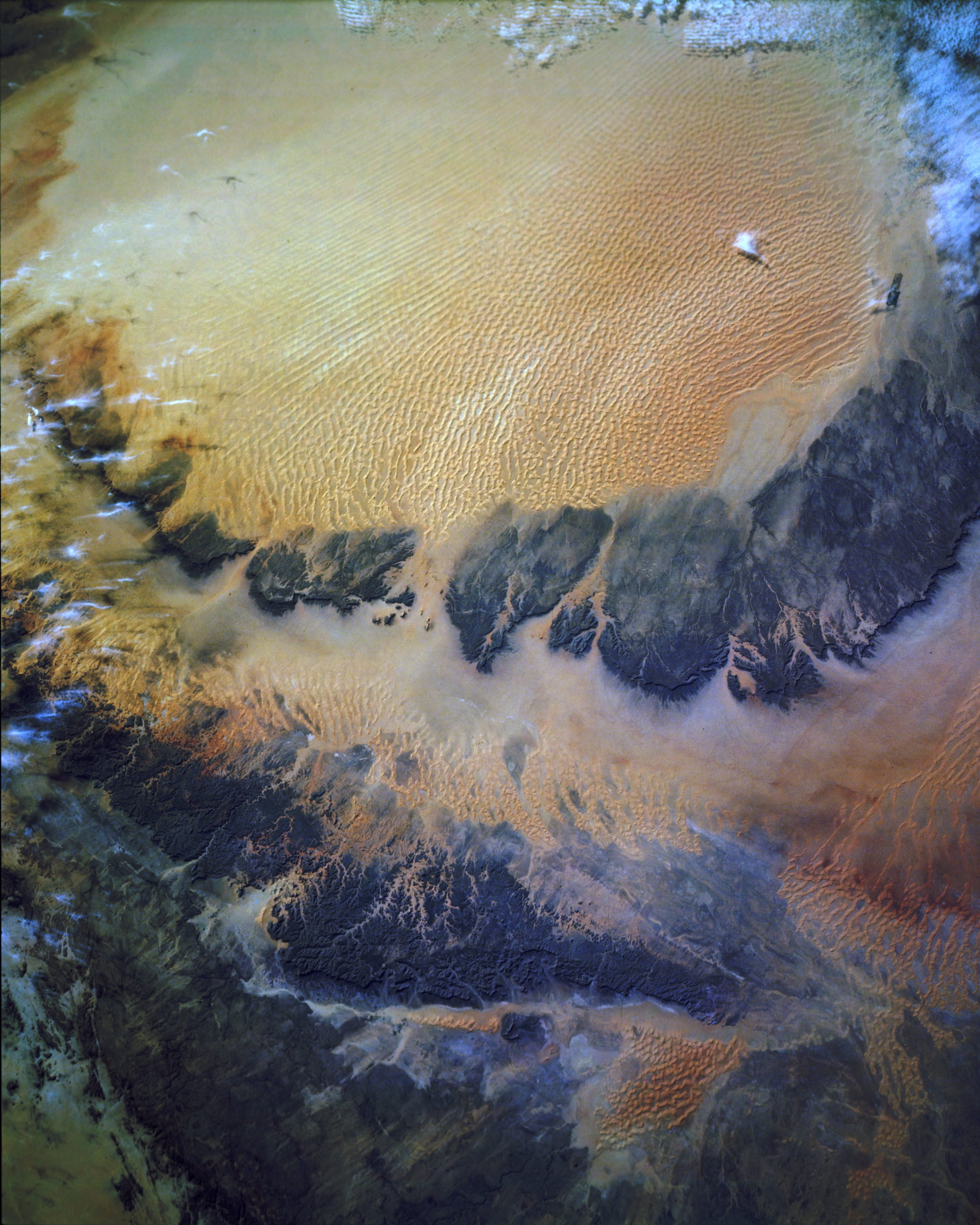

Designed to acquire the first-ever spectra of the diffuse, low-energy “soft” X-ray background in the energy band from 0.15-0.28 keV, DXS included a pair of large-area Bragg crystal spectrometers, which “rocked” backwards and forwards to obtain complete spectral coverage along an entire arc of the sky. During STS-54, it would identify large quantities of hot gas in the interstellar medium, close to our Solar System, and its importance was so high that an additional (seventh) day was provisionally added to the mission “if DXS requires additional time to achieve mission success”.

As such, Endeavour—NASA’s newest orbiter, having only entered service in May 1992—was loaded with enough consumables to support a seven-day “basic” STS-54, plus two additional days to cater for unforeseen issues, such as poor weather at the landing site or other difficulties. But as 1992 drew to a close, STS-54 remained a relatively “vanilla” flight, with TDRS having flown on multiple previous missions.

Then, on 25 November, NASA added Extravehicular Activities (EVAs) onto three future shuttle missions to “fine-tune the methods of training astronauts for assembly tasks in space” and “increase the spacewalk experience levels of astronauts, ground controllers and instructors”. It was noted that EVAs would only be added on the proviso that they did not impair any mission’s primary objectives and the first flight to benefit was STS-54.

At the start of 1993, with a major EVA task anticipated before year’s end to service and repair HST, only eight of NASA’s 90-strong active-duty astronaut corps had spacewalking expertise. For STS-54, Harbaugh and Runco had undergone generic EVA training, in case they had to go outside to manually close Endeavour’s payload bay doors, but their work swiftly moved into high gear in the weeks before Christmas 1992 as plans crystallized for a “real” spacewalk, lasting around five hours.

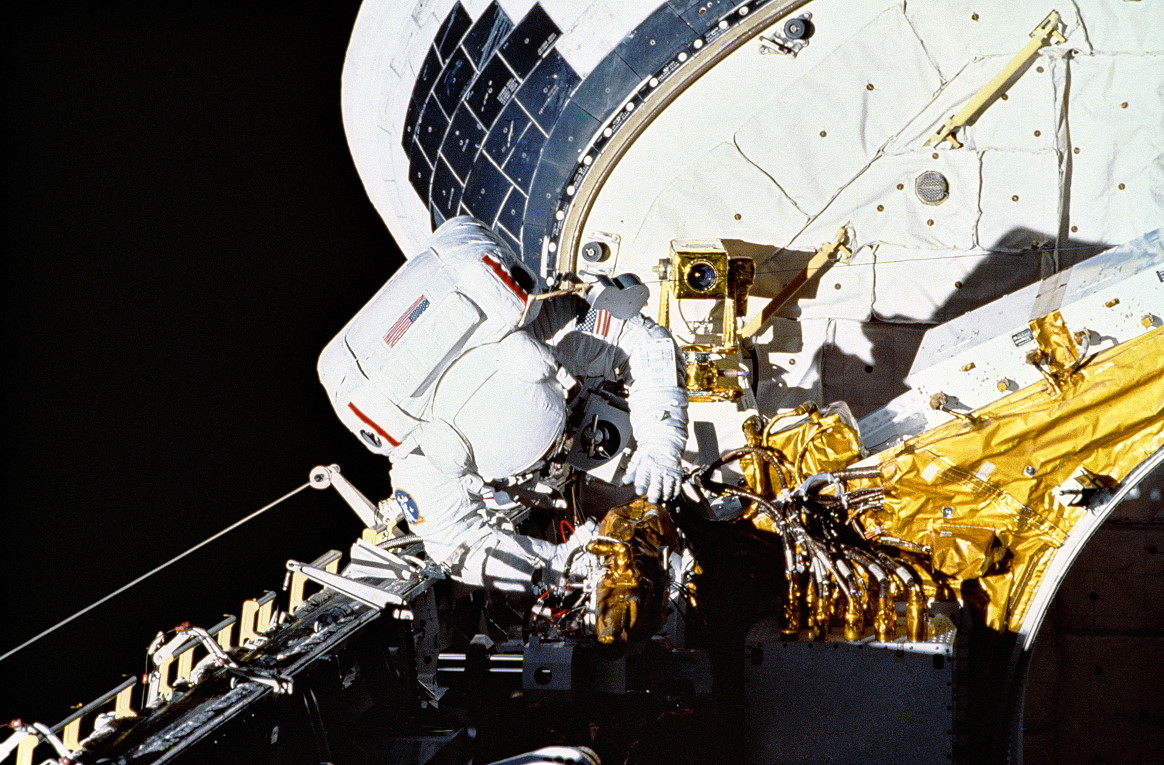

Their tasks included moving around the payload bay, with and without large objects, as well as completing close-alignment work and installing mock pieces of equipment. It was mandatory for their EVA to start and end at mandated times, for the critical DXS observations had to be suspended while they were outside.

Liftoff of STS-54 occurred from historic Pad 39B at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida. According to the pre-flight press kit, Endeavour’s launch was scheduled for 8:52 a.m. EST, but was delayed seven minutes to await the resolution of a Launch Systems Evaluation and Advisory Team violation.

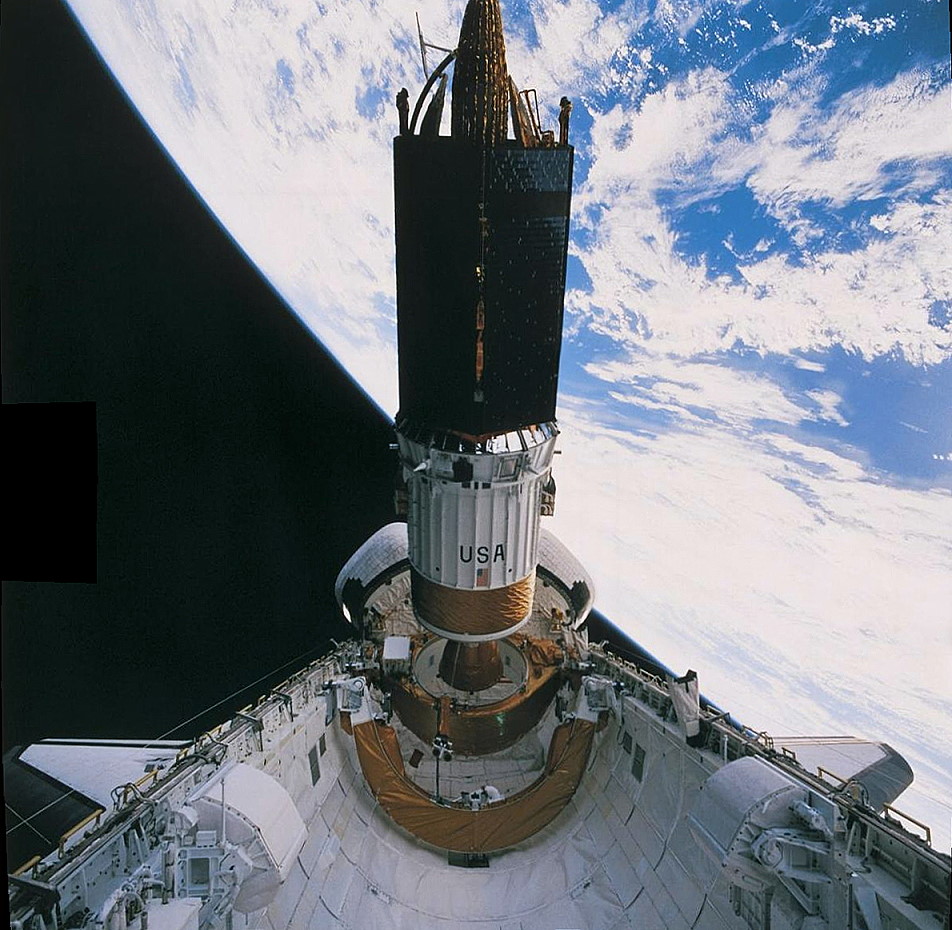

With the violation resolved, Endeavour roared aloft at 8:59 a.m. EST and was inserted satisfactorily into low-Earth orbit, at an altitude of about 190 miles (305 kilometers), inclined 28.45 degrees to the equator. Six hours and 13 minutes into the mission, high above the Pacific Ocean, and just north of Hawaii, the TDRS-F/IUS payload was successfully deployed from the shuttle’s payload bay.

Moving out into the inky blackness of space at about a foot (0.3 meters) per second, the deployment process was monitored by all five STS-54 astronauts. Runco led the deployment campaign, with Harbaugh and Helms assisting and providing photographic and television coverage, whilst Casper flew Endeavour from the aft flight deck and McMonagle—temporarily perched in the commander’s seat—handled orbiter systems.

An hour after deployment, the IUS solid-fueled motor ignited to propel TDRS-F on the first leg of its long trek up to geostationary orbit, some 22,300 miles (35,700 kilometers) above the Home Planet. Satellite and booster later parted company and TDRS-F began a weeks-long process of unfurling its windmill-like solar arrays, its space-to-ground communications boom and its C-band and single-access data antennas.

Upon reaching orbit, TDRS-F was numerically renamed “TDRS-6” and became the fifth operational member of the network. The earlier TDRS-B satellite had been catastrophically lost in the Challenger disaster in January 1986.

On Endeavour’s seventh circuit of Earth, the DXS commenced its first scanning pass. Despite early problems associated with high particle counts—which triggered a high-voltage shutdown—an additional 15 orbits-worth of data collection were authorized to complete the instrument’s scientific objectives. By the time STS-54 returned home, DXS had gathered more than 80,000 seconds of good astronomical data.

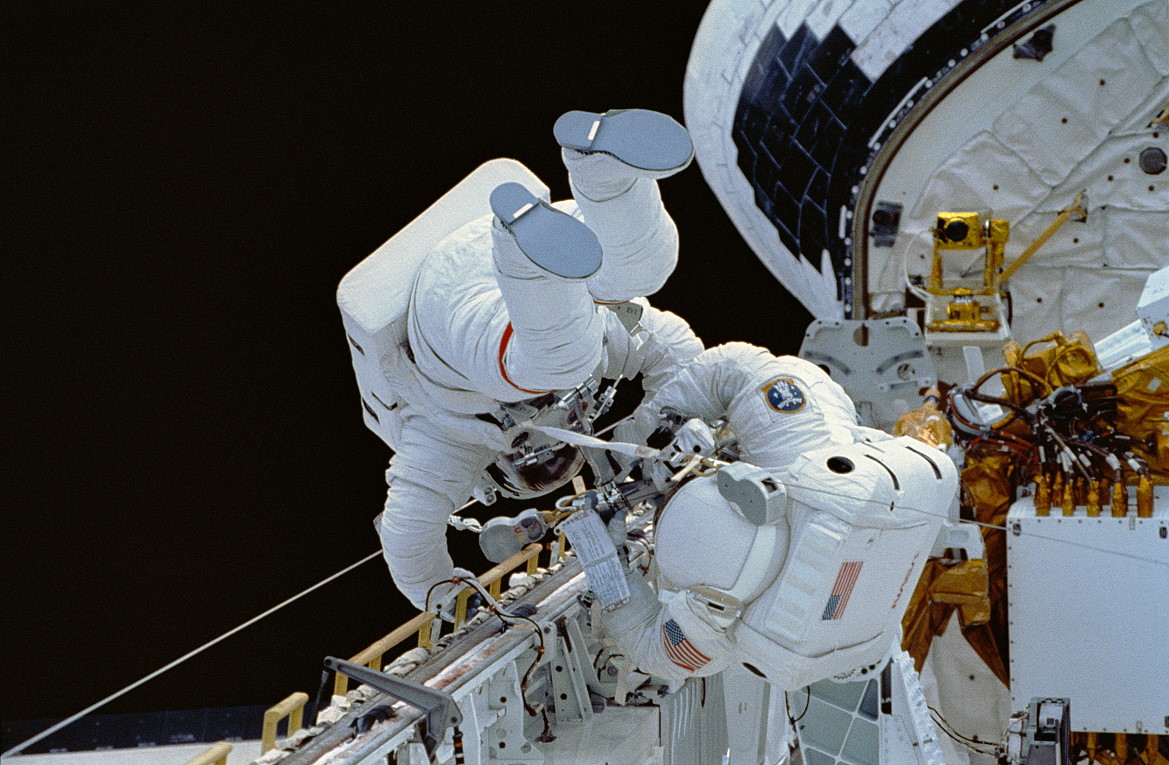

Elsewhere, inside the shuttle’s crew cabin, depressurization began on the third day for Harbaugh and Runco’s EVA. The men entered the floodlit payload bay at 5:48 a.m. EST on 17 January, closely watched by Helms, who acted as an “intravehicular” crew member, guiding them through the multitude of steps.

In fact, McMonagle and Helms assisted the spacewalkers with suit-up and airlock depressurization and hatch closure. “When the time came,” Harbaugh said later, “we were anxious to get out the door.”

Harbaugh opened the outer hatch, “and as I did so, there was just a very small little bit of air pressure left inside the airlock, and that popped open the thermal cover”. As Harbaugh set up tethers, Runco made his way out. “That first view,” he said later, “as you look up the forward bulkhead and see the Earth for the first time, with nothing between you and it, is quite an experience!”

During their time outside, the spacewalkers translated around the payload bay and climbed into foot restraints, with and without the benefit of handholds. “To simulate carrying a large object,” noted NASA’s pre-flight press kit, “the astronauts will carry one another.” Harbaugh and Runco completed their EVA and returned to Endeavour’s airlock at 10:15 a.m. EST, after four hours and 27 minutes.

Spacewalking induced a peculiar sensation in Runco. Years later, describing the experience to a Smithsonian interviewer, he related a free moment in the EVA, whilst waiting for Harbaugh to finish up a task.

“I was standing, facing outboard on a work platform,” Runco said. “The platform locks your feet down and frees your hands for work.”

During underwater training before launch, he enjoyed bending over backward at the knees (“sort of like doing the limbo”) and expected it to be a comfortable stretch, relieving the pressure points induced by his suit. “But in space, the viscosity of the water wasn’t there to slow me down,” he reflected, “so when I relaxed to stand up straight again, the suit “twanged” forward at what seemed like an incredible velocity.

“It really felt like I would come right out of the foot restraint and go tumbling off into space, even though I knew I couldn’t.” Gazing directly into the ethereal blackness, Runco came face to face with what he could only describe as God’s own handiwork.

Apart from the drama of the EVA, the crew oversaw several experiments in Endeavour’s middeck. They examined the effect of spaceflight upon the skeletal muscles of rodents, grew seeds of Arabidopsis thaliana—a small, cress-like plant, with white flowers—and supported 28 commercial studies into pharmaceutical development, ecological life-support mechanisms and agricultural manufacturing of biological materials.

On a lighter note, a collection of children’s toys were flown as part of an educational outreach activity. This “Physics of Toys” investigation featured schools from the hometowns of four of the STS-54 astronauts—the Bronx, N.Y., for Runco, Willoughby, Ohio, for Harbaugh, Portland, Ore., for Helms, and Flint, Mich., for McMonagle—and specifically emphasized elementary kids.

“Live” demonstrations on 15 January included a toy car on a track, klacker balls, a basketball, magnetic marbles, swimmers, a mouse and a balloon helicopter. The demonstration was led by Casper.

Endeavour’s return to Earth on 19 January ran smoothly and without incident. Runco and Helms switched seats for the trip home, allowing Helms to witness re-entry from the right-hand seat on the flight deck, whilst Runco flew downhill in the darkened middeck.

Helms grabbed a camera, ensured its battery was fresh, and shot a bunch of remarkable images during the fiery descent. In the front seats, Casper and McMonagle could be seen tending to their green-glowing instruments, whilst to Helms’ left side, flight engineer Harbaugh kept track of his procedures book, whilst grinning every so often for her camera.

An hour after leaving orbit, at 8:37 a.m. EST, Casper and McMonagle guided their ship to a smooth landing on Runway 33 at KSC, wrapping up STS-54 after five days, 23 hours, 38 minutes and 19 seconds. The five astronauts had traveled over 2.5 million miles (4 million kilometers) and circled the Home Planet 96 times.

“Very nice day, very little wind at the Cape,” Casper recalled later. During their final approach, they spotted the monumental Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) to their right-hand side, outside McMonagle’s window.

And though their mission had begun as a “vanilla” shuttle flight—short in duration, with a primary payload considered unremarkable by the public at large—STS-54 metamorphosized into chocolate with its EVA. And the implications of Harbaugh and Runco’s EVA would become readily apparent as NASA steeled itself for an anticipated “Wall of EVA”: the multitude of complex spacewalks necessary to build the International Space Station (ISS).

The astronauts of STS-54 would play a key role in the ISS campaign, with Harbaugh leading NASA’s EVA Project Office and Helms flying to the station twice in her later career and spending five months there as a member of Expedition 2 in 2001. In many ways, the success of what the ISS has become is linked inextricably to the work done by the crew of STS-54, thirty Januarys ago.

One Comment

One Ping

Pingback:“You’re Not In A Simulator”: Remembering the Ride of Sally Ride & the Achievements of Women in Space - AmericaSpace