Frank Rubio looks set to become the first U.S. astronaut to log more than a year continuously in space, following Wednesday’s announcement by NASA and Roscosmos that the Soyuz MS-22 spacecraft—which sustained damage, likely from a micrometeoroid impact, last month—is not acceptable for a nominal return of crew back to Earth and will be replaced. Soyuz MS-23 will launch uncrewed from Kazakhstan’s Baikonur Cosmodrome on 20 February, providing return capability for Rubio and his Russian crewmates Sergei Prokopyev and Dmitri Petelin, who have been in orbit since last September.

Their return date under the new scenario remains unclear, but ISS Program Manager Joel Montalbano and Roscosmos Executive Director of Human Space Flight Programs Sergei Krikalev did not rule out a possibility that the trio will remain aboard the International Space Station (ISS) until as late as September. Although Soviet and Russian cosmonauts previously spent more than a year in orbit—with Vladimir Titov and Musa Manarov logging 366 days on the Mir space station between December 1987 and December 1988, Sergei Avdeyev recording 379 days between August 1998 and August 1999 and Valeri Polyakov setting an absolute world record of 437 days between January 1994 and March 1995—no U.S. astronaut has ever completed one full solar orbit in a single mission.

The longest single U.S. human spaceflight was the 355-day ISS stay of Mark Vande Hei, which concluded last March. Just two other American astronauts—Scott Kelly and Christina Koch—have spent longer than 300 days in orbit on a single mission.

Prokopyev, Petelin and Rubio launched from Baikonur’s Site 31/6 at 6:54 p.m. local time (9:54 a.m. EDT) last 21 September and safely docked their Soyuz MS-22 spacecraft onto the station’s Earth-facing (or “nadir”) Rassvet module about three hours and two Earth orbits later. They were welcomed aboard the ISS by the resident Expedition 67 crew of Russian cosmonauts Oleg Artemyev, Sergei Korsakov and Denis Matveev, U.S. astronauts Kjell Lindgren, Bob “Farmer” Hines and Jessica Watkins and Italy’s Samantha Cristoforetti.

Eight days later, Artemyev, Korsakov and Matveev boarded their Soyuz MS-21 ship and returned to Earth, wrapping up six months in space. Command of the ISS passed from Artemyev to Cristoforetti, who became the first European woman to helm the space station.

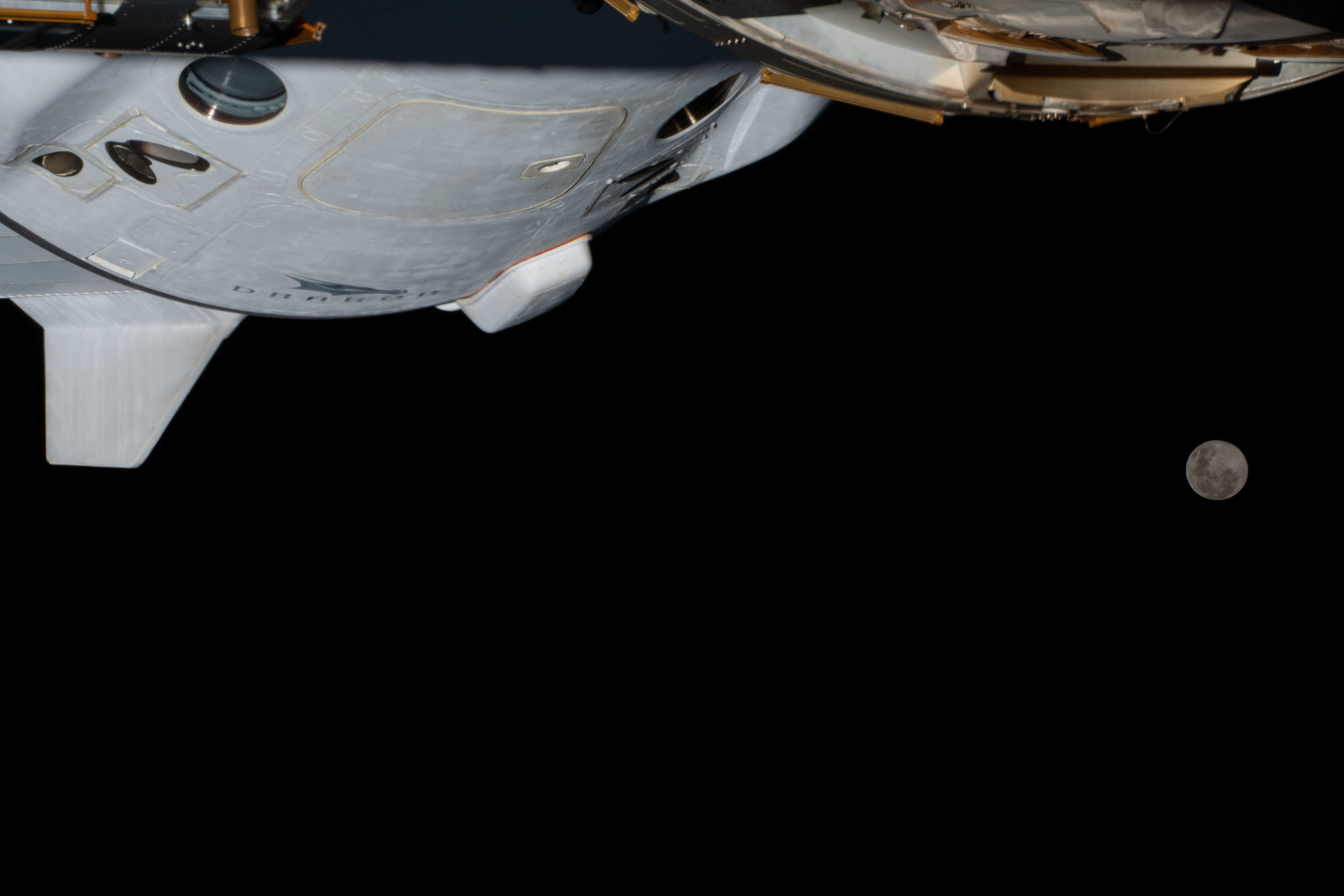

Then, on 6 October Dragon Endurance and Crew-5 arrived: U.S. astronauts Nicole Mann and Josh Cassada, Japan’s Koichi Wakata and Russian cosmonaut Anna Kikina. This set the scene for the departure of Lindgren, Hines, Watkins and Cristoforetti aboard their Dragon Freedom on 14 October, wrapping up their own six-month increment. Command of Expedition 68 passed from Cristoforetti to Prokopyev, with an expectation that he would lead the station crew through his own return to Earth—shoulder to shoulder with Petelin and Rubio, and aboard Soyuz MS-22—on 28 March, after 188 days.

All that began to change at about 7:45 p.m. EST on 14 December, as Prokopyev and Petelin prepared for their second session of Extravehicular Activity (EVA) to relocate a radiator from Rassvet to Russia’s newest ISS module, the Nauka (“Science”) lab. During EVA preparations, ground teams noticed “significant” leakage of an “unknown substance” from the aft portion of Soyuz MS-22 and Prokopyev and Petelin’s spacewalk was canceled as a precaution.

Within hours, a probable source of the leak—the external radiator cooling loop—had been identified. Data from multiple pressure sensors in the loop exhibited low readings and NASA and Roscosmos kicked off a comprehensive external imaging and inspection plan. Soyuz MS-22’s thrusters were satisfactorily test-fired without incident on 16 December and the station’s 57.7-foot-long (17.6-meter) Canadarm2 performed an inspection of the Soyuz exterior on the 18th.

“A small hole was observed,” NASA noted on 19 December, following analysis of the Canadarm2 imagery, “and the surface of the radiator around the hole showed discoloration.” Attention began to turn from early suspicion of an engineering defect to a possible impact from micrometeoroid debris.

“NASA and Roscosmos are continuing to conduct a variety of engineering reviews and are consulting with other international partners about methods for safely bringing the Soyuz crew home for both normal and contingency scenarios,” NASA reported on 30 December. “As part of the analysis, NASA also reached out to SpaceX about its capability to return additional crew members aboard Dragon, if needed in an emergency, although the primary focus is on understanding the post-leak capabilities of the Soyuz MS-22 spacecraft.”

Earlier today, Mr. Montalbano explained that “everything points to a micrometeoroid debris impact”, rather than any kind of engineering defect incurred by Soyuz MS-22 on the ground and stressed that “nothing was off-nominal in the manufacturing of this vehicle”. In his comments, Mr. Krikalev reinforced that there was “not any issue in manufacturing” and stressed that an on-orbit repair was out of the question, due to the inaccessibility of the damage site with a lack of EVA handrails or support structures.

He added that any repair would need not only to fill the hole, but also replenish the depleted coolant, a procedure “so risky that much less risk to just replace the vehicle”. Soyuz MS-23 was scheduled to fly in the mid-March timeframe—carrying Russian cosmonauts Oleg Kononenko and Nikolai Chub, together with NASA astronaut Loral O’Hara—but NASA and Roscosmos elected instead to advance this mission’s launch date four weeks to 20 February and fly Soyuz MS-23 uphill with no crew.

Following the autonomous docking of the new ship—which Mr. Montalbano was keen to describe as a “replacement Soyuz”, not a “rescue Soyuz”; a characterization endorsed by Mr. Krikalev—a period of one to two weeks will elapse before the uncrewed Soyuz MS-22 undocks from the station and returns to Earth. Loaded with cargo, it is expected that, despite its woes, the spacecraft should survive re-entry and will target a nominal touchdown zone in south-central Kazakhstan, close to the town of Dzhezkazgan.

As to conditions aboard Soyuz MS-22 during re-entry, Mr. Krikalev expects temperatures to reach the low forties Celsius (105-110 degrees Fahrenheit), with a possibility of “some overheating of equipment”. Soyuz MS-23 would then remain aboard the ISS to provide a crew-return capability for Prokopyev, Petelin and Rubio, but Mr. Krikalev stressed that the “exact date to send replacements for them has not been decided yet”.

An extended stay-time until September would seem plausible, with the original Soyuz MS-23 crew of Kononenko, Chub and O’Hara correspondingly moving to the next available mission, Soyuz MS-24. When asked if Rubio and his crewmates were ready for a year-long ISS stay, Mr. Montalbano replied that “the awesome thing about our crews is they’re willing to help wherever we ask”, although he acquiesced that he “may have to fly some ice cream to reward them”.

In the meantime, Crew-6 remains scheduled to launch from historic Pad 39A at Florida’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC), no sooner than mid-February, carrying U.S. astronauts Steve Bowen and Warren “Woody” Hoburg, Russia’s Andrei Fedyayev and Sultan al-Neyadi of the United Arab Emirates (UAE). They will replace Crew-5’s Mann, Cassada, Wakata and Kikina and will spend about six months on the ISS.

There remains, of course, the thorny issue of what might transpire should a dire on-orbit contingency arise in the five weeks or so before Soyuz MS-23’s launch. And though Mr. Krikalev admitted that Soyuz MS-22 is “not good for nominal re-entry”, sufficient confidence exists for it to ferry Prokopyev, Petelin and Rubio home in an emergency. Mr. Montalbano added the spacecraft’s other systems remain “solid” and in the event of an evacuation from the ISS, “right now”, the crew would fight the emergency on board “and then if you had to evacuate—which would be a very rare occurrence—you would go in your respective vehicles”.