“Ready. Ready. Grab!”

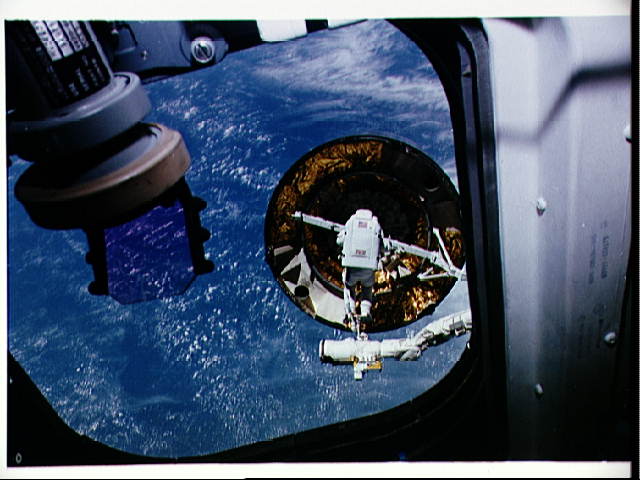

The words of Rick Hieb echoed through the silent Mission Control Center (MCC) at the Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, Texas. The view through Space Shuttle Endeavour’s aft flight deck windows on the evening of 13 May 1992—three decades ago, this week—was quite different from anything seen before.

Not only was STS-49 the first flight of NASA’s newest shuttle, built to replace the fallen Challenger, but it also saw the first Extravehicular Activity (EVA) to feature as many as three spacewalkers. In fact, having so many people outside on a spacewalk has never since been equaled, much less surpassed. The nine days of STS-49 was arguably the most visible shuttle flight of 1992, amply demonstrating that human spaceflight always retained the ability to deliver unexpected surprises.

When Commander Dan Brandenstein and his six crewmates—spacewalkers Hieb, Pierre Thuot, Kathy “K.T.” Thornton and Tom Akers, robotic arm operator Bruce Melnick and pilot Kevin Chilton—were assigned to STS-49 in December 1990, their mandate was to recover the Intelsat 603 communications satellite. It had been delivered into an improper orbit by its Commercial Titan III booster in March 1990 and its prime contractor, Hughes, later entered into a $90 million contract with NASA for a shuttle salvage. Original plans called for Thuot and Hieb to venture into Endeavour’s payload bay and attach a new rocket motor, after which Intelsat 603 would be boosted into geosynchronous orbit, ahead of a pivotal role covering the 1992 Summer Olympics in Barcelona.

After the Intelsat-603 recovery, two more spacewalks, the first with Thornton and Akers, the second with Thuot and Hieb, would rehearse Space Station Freedom assembly methodologies. Thornton’s inclusion made her only the third woman, after the Soviet Union’s Svetlana Savitskaya and NASA’s Kathy Sullivan, to perform an EVA. STS-49 would also become the first shuttle flight to feature as many as three spacewalks.

As circumstances transpired on STS-49, three became four. Moreover, it was the first shuttle flight to include two rotating teams of spacewalkers, a critical prerequisite for NASA to demonstrate its ability to execute as many as five EVAs on a single mission to service the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) and build the space station. On the face of it, STS-49 represented a backward-glance to the shuttle’s pre-Challenger halcyon days. And it was an unusual mission, for in the wake of Challenger it had been mandated that the shuttle would only henceforth not be used for commercial missions. STS-49 was the end of an era.

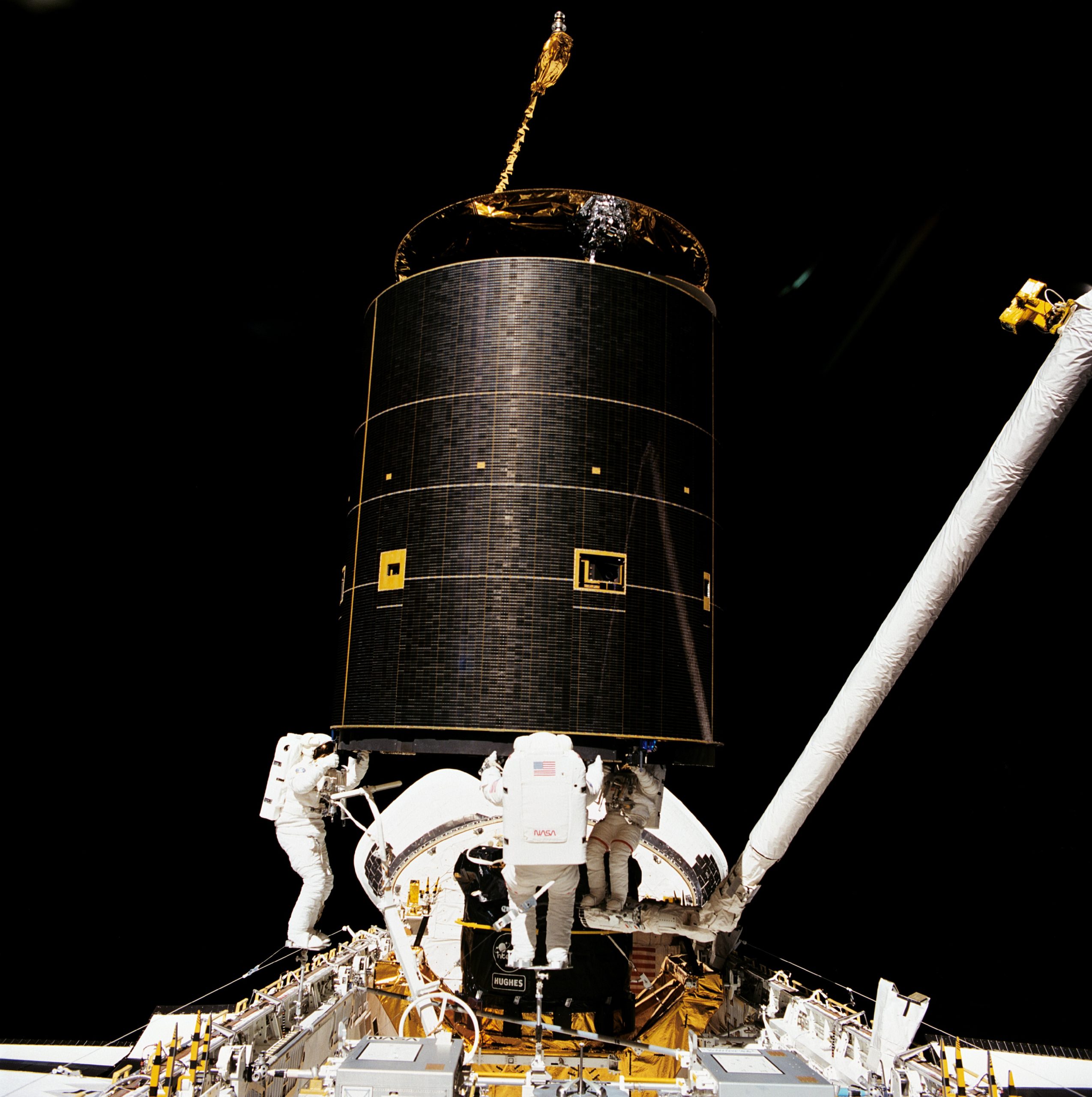

Weighing 9,200 pounds (4,170 kilograms) and standing 17 feet (5.2 meters) tall, Intelsat-603 was an exceptionally large satellite. And that caused concern for Brandenstein. “One of my first concerns when we first got assigned and started working with Hughes on the mission,” he told the NASA oral historian, “was if we try and grab it, if we b bump it, is it going to go out of whack and float away? Part of the requirements from the customer were that we didn’t touch any sensitive area, which left you a very small ring that…had a limited accessibility and that was supposed to the way we grabbed it.”

The mechanism by which Thuot and Hieb would grab Intelsat was a “capture bar”, designed by engineers in the Crew and Thermal Systems Division at JSC. It measured 15 feet (4.6 meters) long by about 3.3 feet (1 meter) wide with detachable beam extensions and a “steering wheel”. As Thuot rode on the end of Endeavour’s Remote Manipulator System (RMS) mechanical arm, he would be positioned close to the base of Intelsat 603 and after grappling it would lower it into a Hughes-built cradle. “There was a lot of analysis done,” continued Brandenstein, “and we were assured that because it was spinning slightly and it had a lot of mass, we could bump it and it would stay pretty much in place and wasn’t going to be a problem.”

STS-49 was originally set to fly on the evening of 4 May 1992, but was moved to the 7th—three decades ago, today—in order to permit improved conditions for photographic coverage of the ascent. The countdown was held for 34 minutes, due to marginal weather conditions at one of the Transoceanic Abort Landing (TAL) sites, but Endeavour speared into a darkening Florida sky at 7:40 p.m. EDT. For Brandenstein, it was the first time he had flown the shuttle through a cloud deck and noted that he could physically feel the heat of the Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) radiating back into Endeavour’s cockpit.

“Happiness on a rendezvous mission,” Chilton recalled later, was the sight of the tiny “star” of Intelsat 603, appearing in the crosshairs early on 10 May 1992. Ever since launch, Intelsat controllers had maneuvered their satellite into a “control box”, some six degrees of arc of Endeavour’s orbit. These maneuvers also served to reduce the giant satellite’s rotation rate from 10.5 to 0.65 rpm. Approaching to within 8 miles (13 km), Thuot and Hieb donned their space suits and were assisted into Endeavour’s airlock by Akers.

At 4:25 p.m. EDT, they opened the outer hatch into the payload bay and set to work. Thuot fastened himself into a foot restraint on the end of the RMS, deftly operated by Bruce Melnick. Drawing closer toward the satellite, Thuot extended the capture bar. But the latches failed to latch. He tried again, without success. And a third attempt proved similarly fruitless.

Brandenstein noticed that Intelsat 603 was beginning to oscillate and drift somewhat, “so I got in my chase-it mode, because I had to keep him aligned”. When Thuot’s third attempt failed, Brandenstein had used a “tremendous” amount of propellant and instinctively knew that the chances of success were now slim. The RMS exacerbated the difficulty, because its joints were being driven into positions which they could not support.

“We decided, though consultations with the ground, to get out of there and try another day,” Brandenstein recollected. “That was a pretty low point, because when we left, it had a pretty good rate. We thought we’d lost this $150 million satellite…and Pierre was particularly depressed because, obviously, he thought it was his fault.”

Thuot and Hieb returned inside Endeavour after three hours and 43 minutes, and later that evening Hughes engineers confirmed that they had managed to stabilize Intelsat. Next day, at 4:30 p.m. EDT on 11 May, the spacewalkers were back outside for a second attempt. “Instead of doing it at night, we were going to wait and do it in daylight,” Brandenstein said. “We decided we weren’t going to even make an attempt until everything was just perfect. Pierre went in and the rotation slowed down.” From Hieb’s position, it looked as if Thuot had completed the capture, but, alas, the satellite again began to oscillate.

Thuot’s alignment was unquestionably correct, but the capture bar refused to seat itself properly and Intelsat wobbled. A few weeks after the mission, Thuot explained to this author that the satellite “was much more dynamic than our training had led us to believe”. As the disappointed spacewalkers returned inside the cabin for the second time—this time after 5.5 hours—they at least knew that the Hughes engineers could regain control of Intelsat 603 for another attempt.

But although propellant reserves allowed it, three rendezvous on a single shuttle mission had never been attempted and Brandenstein recommended a day off to plan the third attempt. In an interview for the Smithsonian, Hieb remembered that the evening of the 11th was a somber time. At one point, Chilton joined Hieb on the flight deck and the pair entered an impromptu brainstorming session. It was a session that would mark a significant turnaround in the fortunes of a seemingly snakebitten mission.

As Hieb and Chilton talked, other members of the crew floated upstairs to join them. The main concern was where to grab Intelsat. The top of the satellite, where the delicate antennas were located, was not ideal, and it was Melnick who suggested an EVA with not two spacewalkers, but three. No excursion in history had ever involved more than two members, partly due to safety concerns and partly because of the sheer impracticability of getting three people into the tiny airlock. On the other hand, Endeavour carried four suits for Thuot, Hieb, Thornton and Akers, so it was at least a theoretical possibility.

“When Bruce said that,” recalled Hieb, “a big mental switch flipped over, at least for me. In my mind, having a third set of hands out there meant that we would be successful, although we weren’t yet sure how.”

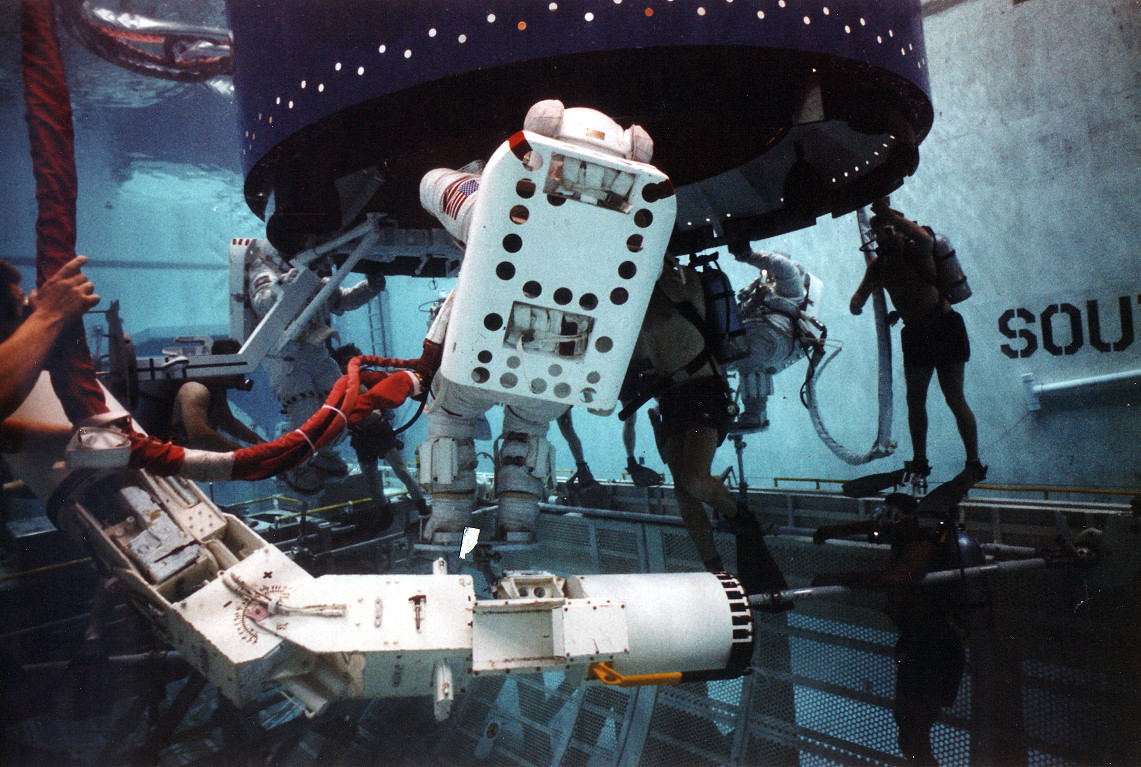

Mission Control knew that the astronauts were still awake, because Endeavour’s monitors had not been turned off. Years later, Brandenstein remembered that it was Chilton who sketched out the three-person EVA and held it in front of the television camera to allow mission controllers to see it. “The big choke point,” Brandenstein said, “was can you put three people in the airlock to get them outside?” In the water tank at JSC, astronauts Story Musgrave, Jim Voss and Michael “Rich” Clifford donned suits and demonstrated the techniques and geometries involved. Their consensus: It was doable.

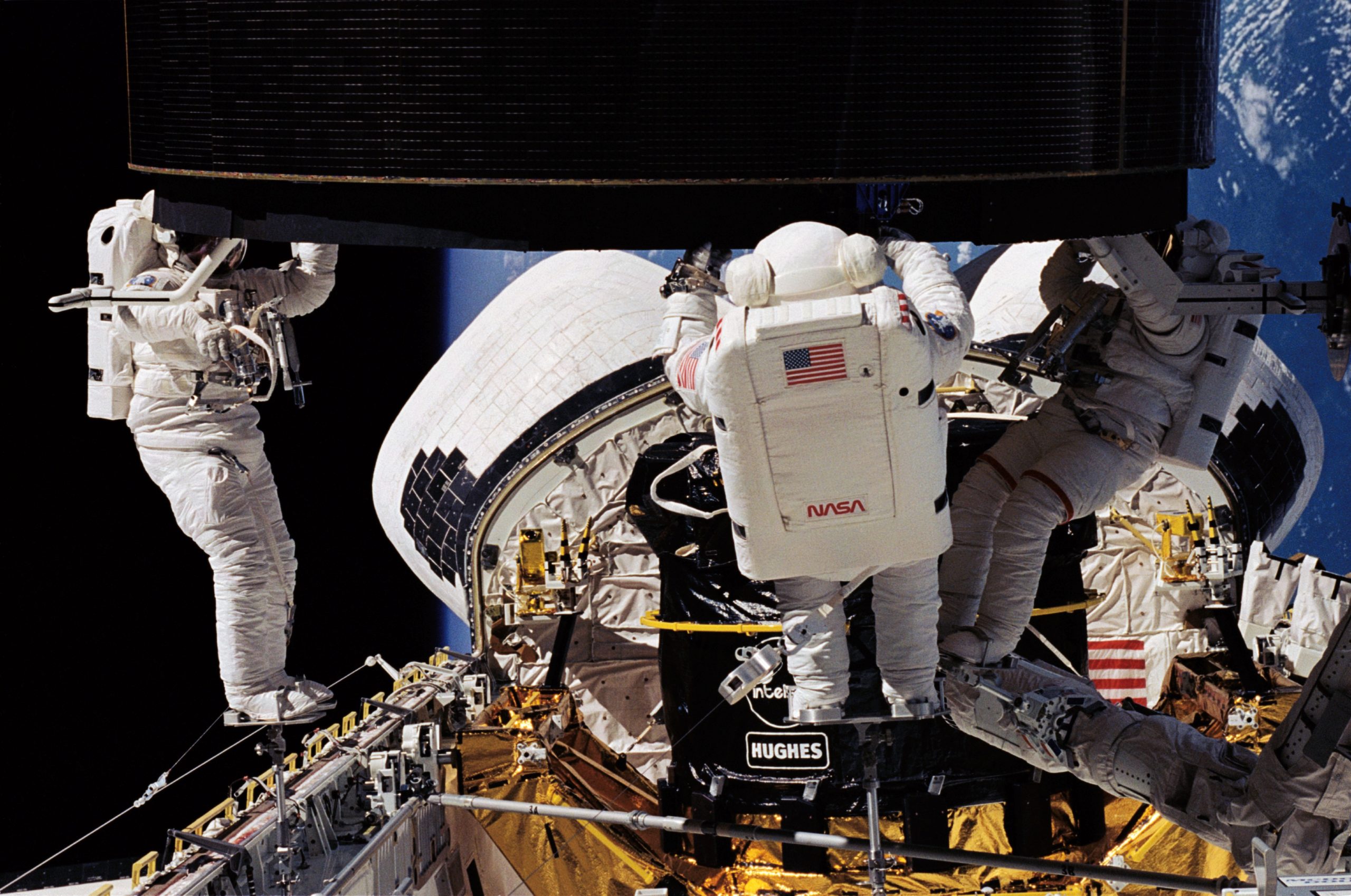

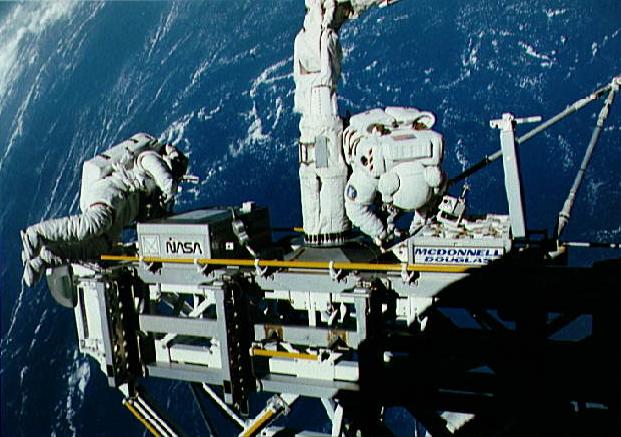

Late on 13 May, the third attempt to salvage Intelsat 603 got underway. Truss members belonging to the Assembly of Station by EVA Methods (ASEM)—a Space Station Freedom demonstration payload, to be used during EVA tests later in the mission—were removed and arranged into a triangular structure for Thuot, Hieb and Akers to anchor their feet. Brandenstein positioned the orbiter directly “beneath” the satellite and controllers verified that its surface temperatures would not exceed the 160 degrees Celsius (320 degrees Fahrenheit) touch limit of the astronauts’ gloves.

With Hieb close to the starboard payload bay wall, Akers in the center, attached to an ASEM strut, and Thuot on the end of the RMS on the port side, the astronauts could do little but watch as Endeavour drew closer. They studied its slow rotation for about 15 minutes, until, on Hieb’s call, they moved in for the capture.

All at once, Thuot spotted a slight wobble. He called the attempt off.

Shortly thereafter, they tried again. This time, the three men grabbed the satellite and held it firmly. The time was 7:55 p.m. EDT. “I actually thought the other two guys had stopped it from rotating,” Thuot said later, “so little force had I applied. Very gently, the thing came to a stop.” From the flight deck, Brandenstein asked them if they had a good grasp. On Thuot’s response in the affirmative, the commander was able to advise ground controllers, with more than a hint of relief: “Houston, I think we’ve got a satellite!”

With Intelsat thus snared, the astronauts removed the steering wheel and installed an extension to the capture bar, which Melnick grappled using the RMS. The satellite was then positioned above its solid-fueled perigee kick motor. After closing four docking clamps and attaching two electrical umbilicals between Intelsat and the motor, the spacewalkers set a pair of deployment timers and retreated to Endeavour’s airlock.

Meanwhile, Thornton prepared to activate the springs to deploy the payload. At first, it did not move. “They had made a change in the wiring of the deploy system,” recalled Brandenstein, “and the change never made it through the process [and] never got into the checklist. Fortunately, somebody in Mission Control apparently knew about it.” Deployment occurred at 12:53 a.m. EDT on 14 May and the satellite vacated the payload bay.

Speaking a decade after the flight, Brandenstein regarded those few days of STS-49 as “one of those missions from hell” and for NASA’s new Administrator, Dan Goldin, it was “a baptism of fire”. Nevertheless, at 1:25 p.m. EDT on 15 May, Intelsat 603’s new motor ignited perfectly, and it was on-station in geosynchronous orbit by the 21st.

As well as becoming the first shuttle crew to accomplish as many as three EVAs in a single mission—a record which they would break with a fourth—the triumphant three-man spacewalk established itself as the longest at that time, at 8 hours and 29 minutes. That record would remain unbroken until March 2001.

By now, STS-49’s difficulties had prompted the Mission Management Team (MMT) to extend the mission by 48 hours past its planned seven-day duration. On 14 May, a record-breaking fourth EVA got underway when Akers and Thornton ventured outside for the ASEM tests. Originally scheduled for two ASEM EVAs, the Intelsat 603 retrieval forced the cancelation of one spacewalk.

Activities included the construction of a pyramid-shaped truss, the unberthing of a Mission-Peculiar Equipment Support Structure (MPESS)—maneuvered by the RMS—and efforts to evaluate the ability of spacewalkers to work at positions “above” and “forward” of the payload bay, including “over the nose” of the shuttle. The MPESS contained two node boxes for the pyramid, a releasable grapple fixture and interface plate and a truss leg and strut dispenser. Five crew rescue techniques were to be trialed, including a lasso-like “astro-rope,” a seven-section telescoping pole and a hand-held propulsive device.

During their seven hours and 43 minutes in the payload bay, Thornton and Akers completed the construction and disassembly of the ASEM attachment fixture, tested the propulsive device, affixed six of eight legs onto the MPESS, and, unexpectedly, were called upon to manually stow Endeavour’s Ku-band antenna, which experienced a positioning motor failure. According to NASA’s post-mission report, this EVA was planned to be RMS-intensive, although the mechanical arm was used to accomplish only a single ASEM task and the spacewalkers’ timeline was further impacted by the Ku-band activity.

Endeavour’s return to Earth on 16 May 1992 brought with it a number of test objectives, the most visible of which was the deployment of the shuttle’s long-awaited drag chute on the runway. Measuring 39 feet (11.8 meters) in diameter when fully unfurled, the chute was designed to reduce steering problems and relieve stress on the shuttle’s brakes and tires. It trailed the orbiter by 89 feet (27 meters) on a 41-foot (12.4-meter) riser.

Following the successful operational of the reefing line cutter, the chute blossomed to its fully inflated condition. Photographic analysis of the landing illustrated that the reefed chute rode at a higher angle than anticipated and the door trajectory differed slightly from ground tests; additionally, its behavior and closeness to the centerline were attributed to the effect of the aerodynamic flow for the fully-open speed brake.

Endeavour’s first mission produced only 36 anomalies, none of which were of sufficient concern to impact the success of STS-49. “They built a beautiful vehicle,” Brandenstein recalled later, “because it’s based on all the other things that diverted our attention on that flight. It was really nice that Endeavour performed like an old pro.” She would continue to do so for the remainder of her 25-mission career.